- Dark Nights of the Universe

- Studio Life: Rituals, Collections, Tools and Observations on the Artistic Process

Jason Galbut

Alex Gartenfeld

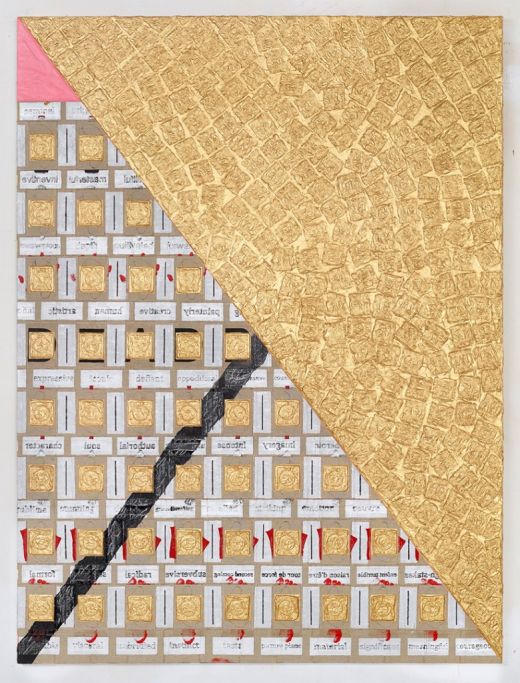

Jason Galbut, Debate, 2013. Acrylic and cut linen on canvas, 8 x 6.

ALEX GARTENFELD (RAIL): I’ve included your work in an exhibition that declares itself to address “technology,” which might seem to be a paradox. Your work involves primarily traditional painting; it could even be related to decorative reliefs. However, I was interested in how your work responds to the some of the futurisms that we relate to Modernism and modernist objects. For instance, in your continuing allusions to the grid, and in your combination of large scale with enormous weight.

JASON GALBUT: Your question has me thinking about the actual movement of Futurism and the irony in using it to interrogate technology today, since the Futurists wanted to eschew art history so badly. Using enormous weight to literally slow down the paintings subverts the Futurist emphasis on speed and motion. In my painting “Election” (2012), technological failure is mirrored by the destruction of the grid. The bottom half is riddled with fallen pieces of rectangular-cut canvas, reminiscent of the notorious hanging chads and the post-minimal actions of Carl Andre. The top section has been curdled and blistered by the incessant indenting of a rhinestone, like futilely trying to puncture a ballot. The grid of an early Frank Stella painting can be very faintly seen beneath the resulting charred and bleak landscape. The subtle red glow emanating from this section evokes the color fields of Rothko while also suggesting a failing LED display.

RAIL: Much of your work involves building up a compositional system, and then using a concerted covering technique to obstruct its visibility. Could you describe the systems you build, and the role of invisibility or obstruction in their operation?

GALBUT: The compositional systems are built up through a series of hunches and dissatisfactions. If something feels familiar I obstruct part of it —or all of it—until it doesn’t anymore. The obstructions add to the buildup. They are as complex in physicality and pattern as the arrangement of images they obstruct. Paradoxically, they amplify what they make invisible.

RAIL: In works like “Protest” (2011-2012), you paint in a style that invokes Dada collage, much of which was informed by the abundance of the “machine age.” Of course, rather than cutting out images, you’re replicating them. How does the style of the Dada collage inform your painting “Protest”?

GALBUT: The Dadaists ditched picture-making to construct their collages without regard to representational schema. “Protest” uses this position as a starting point to construct a picture with representational allusions, resulting in a tension between diagrammatic and representational space. “Protest” is more concerned with how the lessons of Dadaist collage can be absorbed into the practice of painting than with collage itself.

The Dadaists were explicitly concerned with protesting the horrors of World War I and the conditions that allowed it to happen. Today, it’s not clear who is protesting what, or which side has greater currency. “Protest” engages with this current set of conditions while urgently bringing the idea of protest back to the picture plane.

RAIL: The thick application of paint and collage elements in your work is anthropomorphic. How are compositional decisions, or physical parameters, determined in your work in relation to “the human”?

GALBUT: The anthropomorphic quality explores the mediation of the grid by the body, the conditions of the body that determine how a painting is received and the bodily exchanges between the viewer and the painting. The paintings require a life-size scale for this to work. The choice of bodily stand-ins, and how the viewer’s body operates in an institutional context—for example, walking through an interactive installation or circling a vitrine in a contemporary art museum—help determine the proportions.

RAIL: What other factors might you use to determine scale?

GALBUT: Trying to make a great painting on a large scale really pisses people off.

RAIL: Why is that? Because of the proximity of large paintings to the market? Or because of the intrusive nature of the object itself?

GALBUT: The allusions to the market do seem to bother people. This is ironic since dealers are allergic to artists who work on a large scale, unless that artist already has tons of validation. You end up rejected from the galleries and the non-profit spaces. There’s a mountain of bad painting to contend with and many recent art historical movements have been built on expanding critical discourse beyond painting. It’s much easier to write off the idea of trying to make a great painting as passé, because then you don’t have to deal with these challenges. The larger the scale the more egregious the offense, since so many masterpieces are large. What dirtier word is there than “masterpiece”?

RAIL: In “Lottery” (2012-2013), thick globs of flesh-toned paint seem to ooze from the surface of the canvas, which is itself overlaid with an irregularly gridded polka-dot pattern. This painting is among your most compositional, while making the most literal connection between the human form and entropy. Could you discuss this tension?

GALBUT: Figuration endures a lot of abuse. How can one deal with the state of figuration in painting today through non-figurative means? There have been so many markers, substitutes and erasures of the body offered over the last 65 years. Why not abuse them?

RAIL: What are the responsibilities of painting to tell of a certain type of subjectivity?

GALBUT: They are always changing and it’s different for every artist, but I do sometimes get disheartened at the current conservatism of critical painting discourse, which all too often falls into comfortable clichés. It’s important to defy that with whatever one needs to reset the subjective experience.

RAIL: Your latest painting, “Debate” (2013) uses the indentations of candy foil applied to thick paint to approximate the grid structure. The evidence of this material seems to allude to an organizing strategy and to a commercial readymade. How have you worked out a tension between the notions of abstraction and material culture using the readymade, in this painting and prior?

GALBUT: In “Election” and “Debate,” it’s the negative of the readymade imprinted on the painting that provides this tension, while in “Lottery,” it’s the actual object absorbed by the paint. “Debate” is specifically concerned with how the readymade’s movement, and the movement the readymade engenders, interacts with the picture plane. It’s testing those limits.