- MĂIASTRA: A HISTORY OF ROMANIAN SCULPTURE IN TWENTY-FOUR PARTS

- Archival Practices in Contemporary Salvadoran Art

Everybody Rides for Free: a Conversation with Carsten Höller

Nicolas Lobo

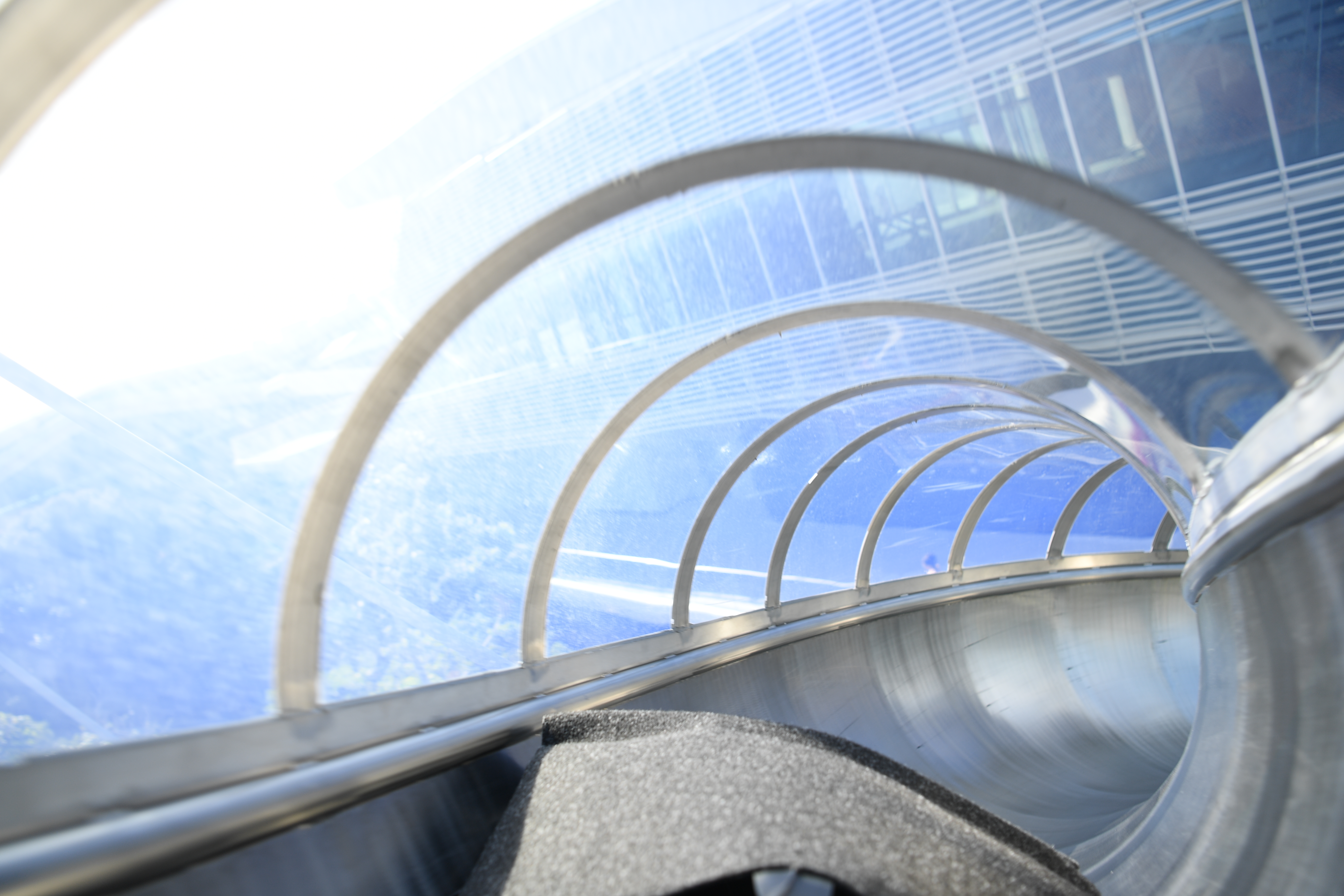

Aventura Slide Tower, Photo by Leonel Diaz

Aventura Slide Tower, Photo by Leonel Diaz

The question came up during the opening celebration for newly installed public art at Aventura Mall. We were standing in a group wondering what really is the job of artists making permanent work for controlled, semi-public spaces. One of us spoke up above the brass band mingling through the crowd. She said, “Somehow, to speak truth to power.” After talking it over we all agreed that was as good an answer as we could hope for. Shortly afterwards Carsten Höller and Chloë Sevigny raced each other down the twin slides of Höller’s Aventura Slide Tower. Sevigny’s scream could be heard the whole way down before exploding out into a throng of arms topped with phones set on video looping mode.

Born in Belgium of German origin, Höller gained international acclaim in the 1990s for work that challenged the experience of public social space. To this end, he has been developing his slide works for the better part of two decades. Beginning at the first Berlin Biennale in 1998, iterations have been installed in the Tate Turbine Hall in London, the Vitra campus in Weil am Rhein and more recently the Heine Onstad Kunstsenter in Høvikodden. Always intended for human use while remaining industrial in appearance, the slides sit squarely between architecture and sculpture.

I sat down with Carsten for a breakfast of guacamole to talk about the history of his slide projects and his interest in symmetry as a social mechanism. We started with our experience of Brussels as a city split in two.

Carsten Höller: You have friends in Brussels?

Nicolas Lobo: A few, but not as many as I would like.

CH: Same here.

NL: People are friendly but keep to themselves there.

CH: It’s tricky; I could speak about the Belgians for a long time. They are very special, very particular. To summarize in one sentence, I would say it’s by far the wildest country in Western Europe.

NL: Wild? Really?

CH: When you think wild you normally think Greece or Sicily in the sense that not everything is under control by the state and conformity has not been imposed. If you compare for example Brussels to Naples you find that Naples is wild in one sense but Brussels is wild in every sense.

NL: How so?

CH: I think all my double ideas have to do with the fact that I grew up in Brussels. Because of the long-standing feeling of a country being split between the French and the Flemish, it’s really schizophrenic. My neighbors on one side spoke Flemish, the neighbors on the other side spoke French but they’d both been to the Congo so they both had the masks and things from there in their homes.

NL: That’s interesting, but when I go to Brussels I see all kinds of behavioral mechanisms everywhere, you know it’s much more organized than, for example, Miami, where people are truly out of control.

CH: Yes, this is what we like about Miami. But Belgians are also out of control in so many ways, for example Belgians are some of the worst dressed people in Western Europe. There is so much ugliness in the streets.

NL: Although the Flemish are so interested in fashion…

CH: I think it’s a countermovement because of all the ugliness. Sometimes you see people on the street and you ask yourself how on Earth can you come up with such an idea, “What the fuck?” that’s how they dress.

NL: “What the fuck” style?

CH: They really don’t care, which might be changing a little bit.

NL: I see what you’re getting at.

CH: If you like, we’ll meet in Brussels some day and go out to some Congolese clubs. What’s nice about Brussels is that the immigrant populations are not on the outskirts of town, they are smack in the middle.

NL: You mean like Saint Boniface?

CH: It’s really Matongé next to the boulevard, and around the corner you have the North African neighborhood. I don’t know what you could compare this to because most other big cities have a center that is more or less the same everywhere shopping malls and things like that. The poor are usually pushed to the outskirts, but in Brussels that’s not the case.

NL: You spend part of your time in Ghana right?

CH: Yes I have a house there, I love West Africa and Ghana is a great place. My house there wasn’t planned, it just happened. I was having a few beers with a friend in a little hotel, the idea came up and that’s it. That was nine or ten years ago.

NL: Do you work there too?

CH: That’s the problem, I go there to work but then I don’t get much done. I go there because I’m able to do nothing.

NL: So you do the best kind of work there.

CH: Yes in the sense that you’re sitting on a chair staring into the void not doing what you have to but going through other things instead.

Aventura Slide Tower, Photo by Leonel Diaz

Aventura Slide Tower, Photo by Leonel Diaz

NL: Let’s talk about how you came to the idea of slides…

CH: I think it was a misunderstanding as it sometimes is. I did something in ‘96 at the Hamburg Kunstverein, it was maybe the first big show I ever had. The show was called Glück, which in English would mean happiness, fortune and luck all in the same word. I wanted to see if it was possible to make an art show that entrances peoples moods. I wanted to make an art show that somehow brought people to a certain level of happiness. I decided to make a kind of amusement park, not in a purely bodily way but including the body. And one of the things in the show was a hut and on the outside was a material that is used for artificial ski slopes. From the top of the hut was a slope coming down and there was a kind of sled to be used to sled down. Anyway, the curator at the Kunstverein in Berlin hadn’t seen the show but he had heard about it and understood it as a slide rather than a slope. So he asked me about the slide I had made and I said, “Not really but now that you say it I quite like the idea.”

NL: A misunderstanding, that is a good place to start.

CH: This is only clear to me now but I was not really interested in making artworks that have only physical qualities. I wanted something that I could use to create a scenario where the audience is not just a viewer.Not just looking at the work but being part of it and noticing the other people visiting an exhibition, I wanted to bring them in too.

NL: I remember going to see your show at the New Museum in New York a few years ago and it was a quiet day in the museum. When I walked in the guards were telling jokes from one floor to the other through the slide, using it to communicate.

CH: The guards, they loved me there. Even when I go today they are all happy to see me. I had such a great time.

NL: Some of the earlier slides including the one at the New Museum seemed to be about going from one space to another, working with the architecture. This new one and the one at Vitra are freestanding. The experience is completely self-contained. How does that difference work for you?

CH: The freestanding ones have a tower; they both have a clock like official landmark buildings.

NL: Here, sliding is more of a self-contained experience rather than a bridge between two spaces.

CH: Yes. It’s really not part of any architecture other than what we build to support it. In this case it creates a symmetrical experience about right and left. The experiment is to see if it makes a difference whether we go clockwise or counterclockwise.

Aventura Mall, Carsten Höller (left), Photo by Pierre Bjork

Aventura Mall, Carsten Höller (left), Photo by Pierre Bjork

NL: There is a small moment of anxiety at the top, when you decide which slide to take.

CH: Yes, I like that very much. I often organize my shows like this where there are two entrances. Also, there is never a qualitative reason to take one or the other.

NL: So the moment of choice primes you for the experience? Puts you in a certain mind frame?

CH: Well it creates a certain awareness of making a choice, but there is no choice really because although you have two possibilities they are the same. Or, maybe they are not the same because nothing is really ever the same. I did two slides this way in London, at the Hayward Gallery. They were called isomeric slides because an isomer in organic chemistry is a molecule that can exist in a right fashion or a left fashion. In organic chemistry the use of these isomer molecules can create very different results depending on their orientation.

NL: So the symmetry is generative?

CH: As we said, all of this comes from Belgium. The thing that I find amazing is that Belgium doesn’t realize that the division in the country is not a problem but really a fantastic situation. It’s not about unity at all, the luxury is to not decide. Why do you need to make a preference all the time? Why don’t we have a culture that can entertain two possibilities at the same time? Is it because our minds work in a linear way? Of course linearity is not difficult to understand, language is mixed in there. But computers work in a parallel way, so perhaps now we should think in parallels also.

NL: I agree people tend to think in linear ways but then again differentiation is everywhere no? Guacamole or eggs? Tea or coffee? This is the substance of every moment for us.

CH: OK, but guacamole is a kind of mixture. It’s not just avocado. I’ve been working on an idea for a restaurant. I’m publishing a manifesto called The Brutalist Kitchen in reference to brutalist architecture. The idea is that you cook only one ingredient. You don’t mess it up with all kinds of other things but especially you don’t look for combinations. Normally cooking is based on combinations, a classic would be… I don’t know duck with orange sauce, why not make duck with duck sauce? It’s not about being minimalistic, it’s about keeping ingredients isolated. So you can come to the restaurant and order two or more things and make your own combinations. The restaurant will be called The Brutalist.

NL: Hmm, so brutalism as a general idea applied to a restaurant, I think of the slides as brutalist, the way they are organized and their appearance. It’s funny to think of them in line with the strange history of brutalism here in Miami, kind of a last wave of brutalism, much later than the UK and Eastern Europe. Our brutalist architecture really came into being during the eighties when the rest of the world had already moved on.

CH: Where are these buildings?

NL: Mostly civic buildings, city halls, libraries, things like that, for example the Miami police station.

CH: Yes, I saw that one.

NL: Something interesting happened to me on the way to meet you. I came in through the hotel lobby and thought I’d go see the pool area. When I tried to come back the hotel wouldn’t let me back in. No one told me to leave but the only place I was allowed to go from there was to exit the property towards the beach. It reminded me to ask you about the way the slides work in only one direction.

CH: Yes, it’s totally unidirectional and without surprise. Everything is a given. Also you go down at a certain speed, it’s not under your control which I find interesting because there is nothing you can do, you have to really let go and at the same time it’s creating this little high. It’s really like sheer madness. Sometimes people say it’s like an orgasm, a release.

NL: A feeling of leaving your body because it’s so much in the moment, like a circuit breaker flip.

CH: Yes but as you said before everything is controlled. There is no surprise. You know everything that is going to happen. No more decision making. Everything is taken care of.

NL: Everything is taken care of.

CH: With stairs you can walk slow, you can walk fast. There are different ways of doing it.

NL: Even an escalator allows you to run the opposite way.

CH: The slide is a kind of behavioral homogenizer.

NL: Yes you have no choice at all. Maybe that’s getting to the core of what felt strange for me. You are confronted with this moment of choice; left slide or right slide, and then suddenly you have no choice at all. It’s a reverse chaser like having the lime before the tequila.

CH: But where is the salt?

Nicolas Lobo is an artist based in Miami and Brussels. He sometimes records conversations with other artists and on occasion publishes them.