A detail of Daniel Arsham's Welcome to the Future at Locust Projects.

ALEXANDRA CUNNINGHAM CAMERON (RAIL): When was the last time Daniel Arsham had a show in Miami? And I specify Daniel Arsham, because I’ve started to think of you as having multiple creative personalities.

DANIEL ARSHAM: My last show was in 2010 before Emmanuel’s gallery closed. But I have a longer history of showing in Miami. We started an exhibition space called The House in the early 2000s and I had a space called Placemaker, which is actually the same space that Locust Projects occupies now.

RAIL: I remember going to The House when I was young and being blown away. My Miami art-viewing experience had been limited to the museums and the Coral Gables galleries. I couldn’t believe the city had something so raw. But how ironic that you’re coming back to show in a space that’s part of your biography, and the description of the show is a fictional archeological site, excavated into the ground.

ARSHAM: I’m going to dig a 25-foot diameter hole into the ground of the gallery. I’m cutting the concrete open, gutting it out, removing all material, then filling it with thousands of objects. Iconic objects from everyday life, like your Blackberry, telephones, cameras cast in geological materials—volcanic ash, obsidian, steel and ash, glacier rock dust, and crystal—which happen to form a perfect gradient from black to white. Within the hole there will be this gradient that starts with ash at the exterior moving through the other materials to crystal in the center.

Daniel Arsham, Obsidian, Steel and Ash Eroded Radios, 2014. Volcanic ash, shattered glass, obsedian fragments, steel fragments, hydrostone. 122 x 56 x 14 cm. Photo: Claire Dorn. Courtesy Galerie Perrotin.

ARSHAM: Craig has actually been really supportive. The engineer is the one who initially said, “No. You can’t do this.” The ground underneath the space is very complex; there are a lot of different layers of stuff, they want to make sure that when the ground is excavated the surrounding area is compact enough that it won’t interrupt the structure of the building.

RAIL: At what point do you hit water in Miami?

ARSHAM: It’s actually really close. Normally it’s between 8 to 10 feet; there it’s like at 15 feet. So, I’m not digging that far down at all. The initial proposal was very deep and the audience was going to be able to walk into the hole, and I could’ve done that, but it would’ve meant that the hole had to be so much smaller. So I opted for a larger scale that’s less deep.

RAIL: That’s going to be beautiful.

ARSHAM: And then the space—there will be nothing else in the space; just clean volume.

RAIL: How did you choose the materials?

ARSHAM: They’re materials that I’ve worked with for a long time already. I chose them initially because they make us think about time. To see a Blackberry rendered in volcanic ash gives you a sense of time that is not a sort of tromp-l’oeil effect. It actually is this material that signifies aging.

RAIL: Is the selection of objects autobiographical?

ARSHAM: Some of them have a particular resonance to me, and some of them are just iconic. When I am looking for a Polaroid camera to cast I’m going to be looking for the polaroid camera that we all remember. It’s going to look kind of like a uniform dump, where all these recognizeable objects have been collected.

RAIL: The most beautiful waste site.

ARSHAM: Did you see that a volcano erupted in Japan over the weekend? There were these photographs in the Times that showed the rescue workers all wearing orange and green inside an entire village white from the ash and it looks like a Lego environment. There’s something in that—the homogenization of the color and the palette makes these materials feel like they are real and not real.

RAIL: What’s the earliest object in the collection?

ARSHAM: There’s a Rolleiflex camera that’s probably from the ‘60s.

RAIL: So, the objects are beyond you? They’re not just from your lifetime?

ARSHAM: No. They actually have nothing to do with me in particular; they have to do with you, or anyone else. I started making these works on a trip a couple of years ago to Easter Island. On the island, there were archaeologists re-excavating a Moai [the giant statue] that had been previously excavated 100 years ago, and they had photographs of this original excavation. So, they were re-excavating it to determine what effects acid rain and the environment have had on the particular striations of it, and when they were excavating it they found tools that the archaeologists had left 100 years ago. So, you have this mixture of time where the things the archaeologist had left are also catalogued as archaeological finds. And it struck me that there was this bizarre confusion of time: you have the statue that’s 1,000 years old, you have this ruler, that was 100 years old, and in a couple 100 years the time between them kind of collapses, and in 1,000 years they’re aversely from the same time period. When I got back I brought some ash from the island and made my first camera out of it.

RAIL: Did you make the entire selection of objects? Or where you inspired by any of your collaborators, or friends, or people in your life who were touched by certain objects?

ARSHAM: I selected all the objects on eBay.

RAIL: [laughs] That’s amazing. Is there going to be a parallel exhibition of the original eBay finds somewhere?

ARSHAM: No. They get destroyed in the process of the casting. So, I have half a ruined Gibson guitar in the studio. But eBay is a huge source for all of these things. To find the iconic Polaroid camera, if eBay didn’t exist it’d be a process of trolling through secondhand stores for years. eBay is like this contemporary library of Alexandria.

RAIL: It’s too bad that eBay doesn’t have a sold catalogue. You know? Where you could see past eBay results.

ARSHAM: You don’t even need what’s sold. You just look at what’s there at any given minute. The auctions that are ending in the next ten minutes can define half of human history.

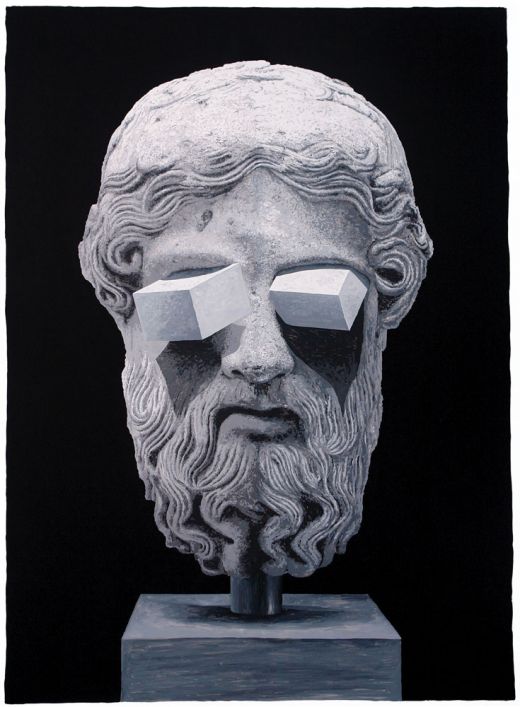

Daniel Arsham, The Eyes, 2010. Gouache on mylar. 233.3 x 178 x 5 cm. Courtesy Galerie Perrotin.

ARSHAM: Certainly, I have a lot of history with the city. There’s a community there that follows what I do. I’ve been in touch with a lot of people there. A lot of people from Miami have seen this work on Instagram, or my website, or whatever—but it’s the first time that people will be able to see it in person. This will be my first show in Miami in five years.

RAIL: Really? It seems so strange that it’s your first show in Miami in five years, and I was going to ask if you still think of yourself as a Miami artist considering that you’ve been in New York for the last fifteen years?

ARSHAM: Miami still has an influence on my thinking and people are often surprised when I say I’m from there. Where you come from always has something to do with what you continue doing in life.

RAIL: But you’re an important part of Miami, an important chapter of Miami’s contemporary art history with Placemaker, the House, and this group of Miami artists that built a community that seems to be dissipating now.

ARSHAM: My feeling of Miami was that it was a really special moment that happened. It was a convergence of many different things—all the art schools like DASH and New World that brought up my generation. We were just coming out of school when Basel first came to the city and in the first years of Basel it wasn’t unusual to have someone like Emmanuel [Perrotin] willing to come into a studio and see work. But, that’s definitely not happening anymore. I think once that moment left it became much more difficult, and it’s part of the reason why I felt I had to leave Miami. I had reached a plateau. There really wasn’t much for me to do. And I was starting to exhibit much more in Europe—I actually have barely shown in the States, which is weird. Miami did a lot for me at a certain moment and then there wasn’t much more that it was going to do.

RAIL: I do see your work everywhere. It’s almost like I should create a Daniel Arsham global scavenger hunt. In the last week, I had a meeting at the Standard East and saw your installation there; I was at the U.S. Ambassador’s residence in London and saw your work there; I was in the cellars of Perrier-Jouët champagne in Epernay and you were there also.

ARSHAM: You probably couldn’t even drink champagne, right?

RAIL: Despite being seven months pregnant I had to have a little bit, but more importantly, I hadn’t realized the full concept of what you did for Perrier-Jouët which is also very much entrenched in in this idea of time passing.

ARSHAM: Time. That was a really amazing project because they gave me the space to figure out this idea and I went and visited, I went to the cellars. I spent a bunch of time with Hervé, the cellar master. He drove me around in a little cart through the tunnels. The cellars are almost like a time capsule, right? He can go to a particular area of the cellar and he knows. “This vintage is from whenever.” And he knows exactly everything about it. He remembers the weather that happened that year.

He has a journal that says what the weather was like every single day, what the humidity level was, all of that. So, the project was to essentially create a double case for the magnum bottle that when purchased, one you would take, the other one would go into the cellar and would stay there for up to 100 years.

RAIL: There is a certain power to being in a small room with all of the bottles of champagne that people have designated for their heirs, or for important people in their lives, and imagining these moments…

ARSHAM: …In the future.

RAIL: Yeah! Sitting there drinking their champagne and remembering the person who left it to them; it gives you goose bumps because it’s choreographing a moment in the future. But the choreography of experience is something that is also a big part of your work. I mean, despite the theatricality of the Locust Projects exhibition, and the spaces you design with Snarkitecture, you also have an ongoing collaboration with Jonah Bokaer, and a history of collaboration with Merce Cunningham starting when you were really young.

ARSHAM: The future is something that has come a lot to my works, just thinking about the future, imagining it. And I’ve also been working on these films…

RAIL: Oh, really?

ARSHAM: I’m working on this series of nine films called “Future Relic.” The basic idea is that there are these nine stories that come together to create a full-length film. I shot two of them, and we’re shooting the third one next month. The first four of them I’m going to show at the Tribeca Film Festival next year, and then the full-feature length the following year. It’s been this whole new, magical way to work because I managed to meet the right kind of people. I have an amazing producer, amazing D.P., and the talent primarily through OHWOW. James Franco’s going to be in the next. The one we’re shooting next month is with Juliette Lewis.

RAIL: That’s amazing!

ARSHAM: They’re really interested in these things I think because it’s so foreign to what they do. I’m directing it and I kind of don’t know what I’m doing; I work with it sort of like I would with an architecture project. And I think it’s refreshing for them to be in an environment that, while all the tools and everything else is the same, the way they are manipulated is different.

RAIL: So, the next formal collaborative enterprise you’re going to start is the production studio?

ARSHAM: I started it. Where’s my wallet. I just got this on Friday. [He pulls out a corporate credit card]. “Films of the Future.”

RAIL: I’m obviously an admirer of your work, but I have to say that what really attracts me to what you do is the way you work. You have an individual practice but you have formalized these collaborations around you that allow for a completely different type of ongoing experimentation. So many artists collaborate, but they don’t set up a challenge for themselves to continue the collaboration and to see it through as a long-term exercise.

ARSHAM: People have asked me, “You started with Merce. Why did you continue? And why did you continue with Jonah afterwards? And then continue with architecture? And then move into all these different areas?” Part of the reason is that I get a little bit bored with certain things, although there are always things that I go back to. I always go back to the painting. That’s only thing that I do that’s only me; no one’s ever helped me on a single painting. But everything thing else that I do is somewhat collaborative. I think part of it is the desire to try to put myself within a new scenario. It’s not that I care so much about challenging myself, it’s more curiosity. Being on this film set is the most amazing thing for me because I don’t know how anything works, there are all of these dollies, and the technical aspect of shooting, and I need to learn it. It was the same way when I started working with Alex [Mustonen]. I didn’t know how to read architectural plans.

The other part of it is working with other people. A lot of these people that I am able to work with are seriously geniuses. They’re often the best at what they do. Being with James on set—and I didn’t work with him for a super long time, this is a day shoot so I put together this whole film in a day—going back and looking at what he managed to achieve in that amount of time with the direction that I gave him is impressive. His entire role has no speaking lines. Everything is communicated through his action, through the look on his face, and it’s magic.

RAIL: You are also reaching completely different audiences with all of these different collaborations. With dance, with architecture, with art, and now with film, the exposure of your work increases and the opportunity for you to touch a variety of different people that you wouldn’t otherwise is quite extraordinary.

ARSHAM: And to expose people that would never watch dance, or would never look at architecture, or would never go to a gallery. So, it’s a kind of mixing of all those people. And, it’s something that I’ve really tried to do intentionally with Jonah. He intentionally pushes those audiences to crossover.

RAIL: You’re one of the most followed artists on Instagram. Everything you post is liked by 50,000 people immediately.

ARSHAM: This platform flattens everyone out and allows a 12-year-old girl in Korea to have the same voice as a collector in New York. I use it a lot for letting people know what’s happening but also to give them a little bit of stuff they would never see in the gallery: process, a little bit of process, and then a range of novel things.

RAIL: What sort of opportunities come out of Instagram?

ARSHAM: Tons. You discover the people that are following you are other artists, they’re musicians, architects, whatever. And they want to do something together. And they reach out.

RAIL: What is it like to be a young artist and a father?

ARSHAM: I’ve always said that Snarkitecture has children in mind when we design stuff. A sense of play. I take Casper [Arsham’s 20-month-old] to galleries a lot. His reaction is pretty funny. Just what he likes. You’d think all of the colorful stuff, but it’s not even that. I took him to the Roxy Paine show and he was just like staring. I never let him out of the stroller because then he’s going to start batting things, breaking art. He hasn’t gotten to the point where I could teach him not to touch. He will get there. This is why we can’t have nice things. He already broke two of my Kaws toys.

RAIL: Does he give you the opportunity to remember what it was like to be young and less inhibited?

ARSHAM: I think that certainly the way he plays with stuff and some of the things that he’s drawn to—like cartoons. He watches cartoons on Saturdays and he’s been all about this cartoon called Noddy—it’s a British cartoon that has been around since the ‘30s in storybook form. The way that these writers think about how to convey information to the child is amazing. Super simplified. Also, after Basel I’m taking him to Disney World.

RAIL: For the first time?!

ARSHAM: Yes. I love Disney World. It’s one of my favorite places.

RAIL: Oh my God. You are a child of Florida.

ARSHAM: When I was a kid I remember realizing for the first time that the architecture’s all fake there and not only is it fake but it’s all an illusion. For instance, in places like Epcot Center, the buildings that look really tall, they’re not really that tall, it’s all forced perspective. Not only are the buildings sloped like this but on the first floor the windows are 100% sized, on the second floor they shrink to 80%. So if you see a bird land on the top window, the bird’s going to look huge. All of that illusion stuff is what I love about that place. Illusion is something that I use a lot in my work.

RAIL: I suppose that’s a good reason to like Disney World.

ARSHAM: So, I’m going there with him. I’m almost more excited about that than I am about Basel.

Alexandra Cunningham Cameron is the Creative Director of the Design Miami/ fairs. She designs the curatorial program for both Miami and Basel and oversees the company’s year-round events, editorial, and international activations.