The Pursuit of Abstraction

Ivan Shapiro

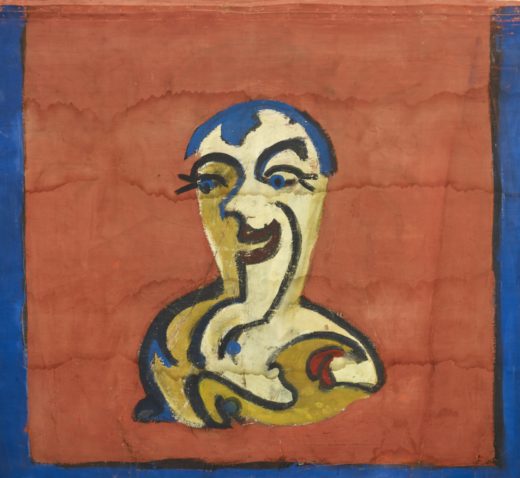

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Theater curtain, 1920 (reverse) and 1931 (obverse, detail). Tempera on canvas, 2.1 x 4.9 meters. The Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection XX1989.480

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Theater curtain, 1920 (reverse) and 1931 (obverse, detail). Tempera on canvas, 2.1 x 4.9 meters. The Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection XX1989.480

UNIVERSITY

OCTOBER 13, 2016–APRIL 16, 2017

World War I and the turn of the century created an anxiety that placed a certain emphasis on science, empiricism, and a search for what was seen as true objectivity. This angst manifested itself in culture: religion and non-representational arts were not only seen as unnecessary, but untrue. The spiritual and scientific realms were viewed as mutually exclusive and unrelated. The Pursuit of Abstraction documents the resistance to this line of thinking that ensued in the first half of the twentieth century.

At its core, this exhibition is about dualities and dichotomies. It is about seemingly unrelated worlds, worlds at odds, and worlds that have more in common than it would first appear. Fittingly, it includes a special 1908 edition of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche’s novel that discusses the death of God and the rise of human-centered conceptions of divinity. Much in the style of ornate religious texts and medieval manuscripts, this particular edition aesthetically elevates this seminal work to the point of sanctification. To paraphrase Nietzsche, one cannot exist without the other; in reckoning between these worlds, it becomes clear that science and notions of objectivity become dogma without religion and art, and viceversa. After all, pseudo-science and ideas of eugenics and racial purity led to the rise of fascism. In this way, art and the language of art becomes a liberating force. This exhibition asks us to examine the necessary entanglement of this relationship. These realms, although seemingly at odds, keep each other in balance. Without art there is no feeling. And without science there is no evolution (of feeling). Ironically, science reasserts the importance of art and religion. Metaphysics makes clear that the spiritual and the scientific exist concurrently. It is this idea of monolithic time and the existence of simultaneous, often contradictory worlds that helped to reconcile the conflict at hand. The Pursuit of Abstraction makes clear that art, much like science, provides a language that helps to visualize the spiritual and divine—the ineffable and unexplainable. Ultimately, both are valid and necessary, and neither is more or less “true.”

This conflict bore splitting reactions within the artistic community. During this period some artists and designers wanted to hold on to prewar aesthetics. They desired a return to earlier philosophical thought and theology, ultimately seeking deliverance back to artistic practices of the nineteenth century that rejected experimentation in favor of invoking biblical imagery and symbolism. Perhaps this was born out of fear, out of a desire to return to simpler times. On the other hand, there were those who sought to embrace the industrial revolution and what would later become Futurism. These thinkers committed to moving forward in order to escape atrocities of the near past. Regardless, both schools of thought were based in disillusionment, as artists searched desperately for ways to assert their relevance in a world that began to see art as superfluous.

This duality is reinforced when one examines the roots of some of the artistic strains included in the exhibition. Cubism is featured throughout, such as in Mary Swanzy’s Propellers (1942), which depicts an industrial scene dominated by fragmented images of protruding aircraft propellers and the stark lines of factory smoke stacks. Here, Swanzy adopts the collagelike composition typical of Cubist works to communicate urban imaginary. Although the intellectualization of this form began in Europe with the appropriation of what was known as “primitivism,” the practice itself began in Africa. Ironically, this “primitive mode” proved most effective as a way of communicating the psychological fragmentation of modern life postwar.

The exhibition is divided into several sections. One section stresses the importance of human ritual. In this space, images of community, such as Henrietta Shore’s Women of Oaxaca (1928–30) and William Penhallow Henderson’s Corn Dance (1926–27) test notions of industry and singularity. These works prize the shared experience. They reassert those activities and services that provide communion. These pieces take note of customs that support the pursuit of mysticism, spirituality, service, and selflessness.

At the centerpiece of this exhibition is Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Theater Curtain (1930). Hung in the middle of the exhibition’s main space, the curtain can be viewed from both its front and back sides. In keeping with the exhibition’s theme of appropriated “primitivistic” imagery, the curtain illustrates ancient symbols of human activity and existence- action and emotion, storytelling, our relationship to ourselves, and our relationship to nature. Made for the Mixed Choir of Davos Frauenkirch, the curtain was born out of the belief that performance represented a cleansing ritual by which the splintering forces of capital and industry could be excavated from mind, body, and spirit. Both sides of the curtain are exposed as a result of reuse. In that way, the seeming vulnerability of its exposure is also what reveals the presence of its strength and resistance.

Unassuming prints of wood engravings such as Michael John Gallagher’s The Deluge (1935–39) and Pamela d’Avigdor’s Storm (1930) illustrate Judeo-Christian notions of guilt and fear—the apocalyptic consequences of science, technology, and other attempts at superseding God. We see metropolitan Babel in the vein of Fritz Lang, as well as biblical images of destruction and rebirth, images that simultaneously allude to the artistic process itself.

The Pursuit of Abstraction, The Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, 2016

Ultimately, both war and scientific discovery created a sense of anxiety and disillusionment that could only be cured by a “leap of faith,” equal amounts abstraction and spirituality. In designing her stained glass windows for a spiritual center in Dornach, Switzerland, Assja Turgenieff believed that, “by admitting spirit to the building’s interior in the form of light, the windows aimed to unite the outer world of objective reality and the inner world of the soul.” With this it becomes clear that the empirical or objective is not apparent unless it pursues and ultimately stands in contrast with the darkness of abstraction.