- Widening the Horror Genre: A Conversation with Victor LaValle

- FUTURE CITIES: MIAMI | RESEARCH INTENSIVE PUBLIC SESSION

Dara Friedman, Perfect Stranger

Amanda Sanfilippo

Dara Friedman, Dichter, 2017. Four-channel HD color video transferred from 16 mm film, with sound, 32 min., 13 sec.; 24 min., 10sec.; 22 min., 51 sec.; 24 min., 46 sec. Edition of 6.

Dara Friedman, Dichter, 2017. Four-channel HD color video transferred from 16 mm film, with sound, 32 min., 13 sec.; 24 min., 10sec.; 22 min., 51 sec.; 24 min., 46 sec. Edition of 6.

November 3, 2017 — March 4, 2018

Like the young woman on the exhibition banner staring down motorists over the Macarthur Causeway, bold makeup, teased hair, mouth slightly open as if singing, Dara Friedman’s mid-career survey at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) is a forceful declaration of its right to exist. A robust presentation, the largest from the artist to-date, Perfect Stranger features works spanning from the earliest days of the artist’s career in the 1990s to 2017.

With a track record of national and international exhibitions at institutions including the Hammer Museum Los Angeles, The Museum of Modern Art, and Public Art Fund, New York, Friedman (b. 1968, Bad Kreuznach, Germany) is known for her performative approach to time-based media. Distinguished in her practice for her influences from an early education in Structuralist film in Germany, Friedman contributes to a distinct legacy but also belies formalism in the pursuit of a far more voyeuristic, interactive and situation-specific mode of filmic production — one that deeply considers the vitality of the world and not only the phenomenon of light.

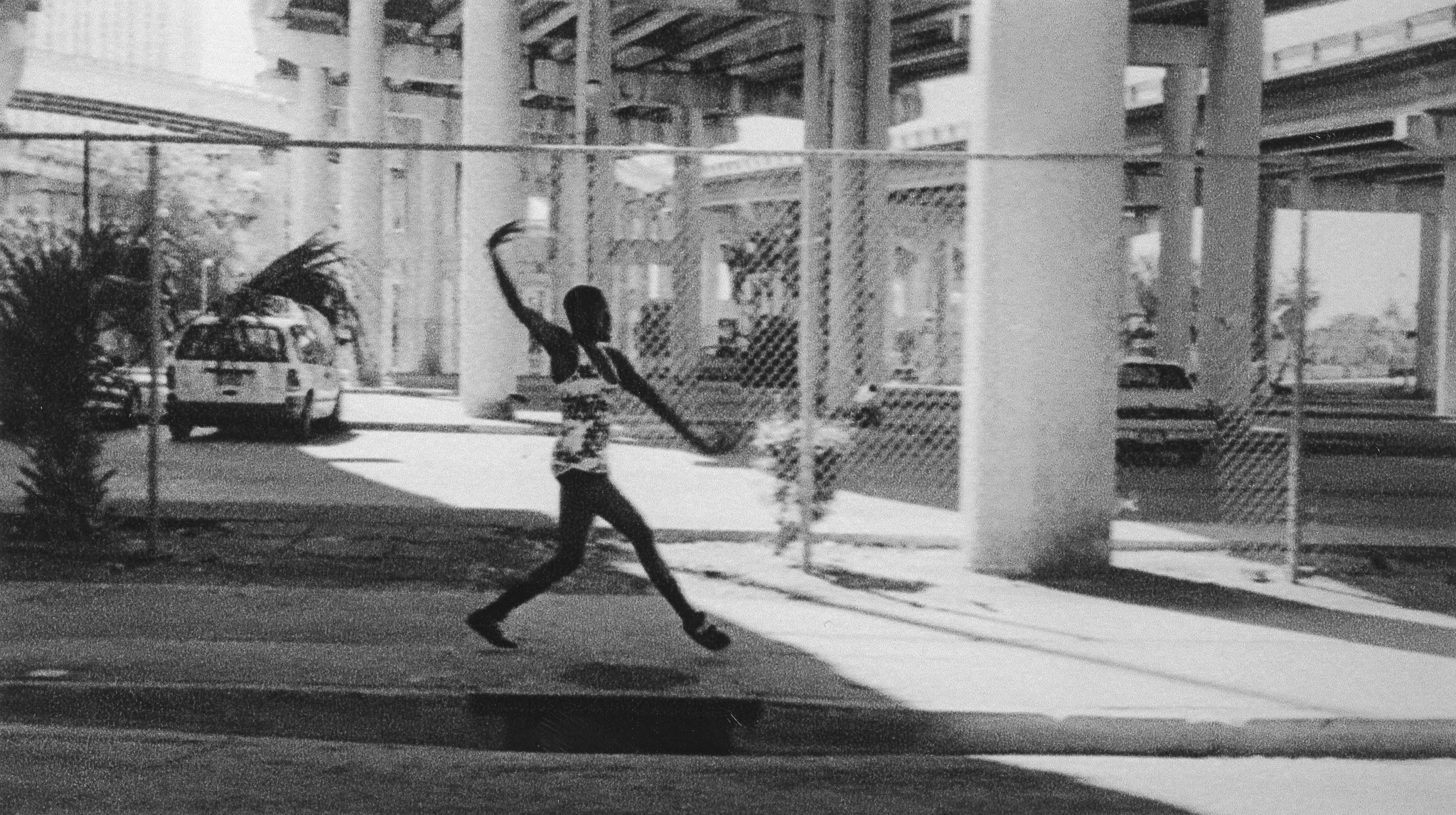

Dara Friedman, Dancer, 2011. HD Black-and-white video transferred from Super 16 mm film, with sound, 25 min. Edition 1/5. (film still)

Dara Friedman, Dancer, 2011. HD Black-and-white video transferred from Super 16 mm film, with sound, 25 min. Edition 1/5. (film still)

At the PAMM, the exhibition is arranged to follow Friedman’s career as she worked through and around a diverse set of ideas, formats and presentation methods in media that includes Super 8mm film, 16mm film, multi-channel video projections, and dueling monitors. While some works are set in studio environments, others sprawl out into the world, offering singular glimpses of Miami and its environs, or the urban density of large cities such as New York and Rome.

What the selected films and videos share is a range of expressions communicated through gesture and motion in choreographed situations or opportunely captured moments. In some, Friedman herself is the performer. Others use actors solicited through casting calls. These remarkably simple, yet deeply resonant works create fundamental, archetypal expressions of human experience. Powerfully, many works champion the freedom of others to be seen and heard, and to share and receive respect in that process.

I have had the opportunity to work with Friedman in Miami where we both live. In 2015, I commissioned Tequesta Ghost, a site-specific performance work for Fringe Projects that was a response to the recent archeological uncovering and subsequent burial of the ancient city of the Tequesta natives. I am also organizing a permanent public artwork — Friedman’s first in Miami. I joined Dara to discuss the mechanics and poetics of her work, and to reflect on the exhibition at PAMM.

Amanda Sanfilippo: Perfect Stranger was a major undertaking. There are seventeen works from a span of more than twenty years of your practice. What are your impressions from this process, and do you see a sense of evolution or change in your work?

Dara Friedman: A close friend pointed out that the first big gallery in Perfect Stranger, with seven early works in it, most with sound, all running simultaneously, is the same in structure as the most recent work, Dichter (2017, also on view), in the project room. Which makes sense because I wanted the mechanism for Dichter to mirror the one of Chrissy, Mette, Kristan1 (2000). In that piece you have a simple action, a woman ripping her silk blouse open and the sound of popping buttons substituted for gunshots. Each woman takes a different amount of time to complete her action, which is simply looped to repeat endlessly. So three women doing the same action in their own time, all together, which creates a structured chaos with no visible pattern, yet is dominated by repetition. Dichter does the same thing; Sixteen people reciting a poem of their own choice, in their own time, looped endlessly, returning to a sort of structured chaos… shouting and talking over each other and then sometimes making space for the one or (an)other statement to stand solo.

So that’s the structure, but the subject matter, it turns out, is also really similar. The women in Chrissy, Mette, Kristan rip their blouses open because they are just so full of their own powerful energy that can’t be contained by their clothes. When I made it I was very newly pregnant with my first child, and the realization of this power to grow human life… within you, was like a… bomb. I mean if that super power doesn’t make you feel like ripping your clothes off…

And then in the most recent work, Dichter, I ask actors in Berlin to recite poems, their choice, that put gas in their tank when they were teenagers, and which they have been carrying around inside them since then. We’re now in these awful, cynical times. Let’s remember what thrilled and energized us in the first place, the urges and desires that made us want to be artists. Let’s remember what that felt like. A poem by Rainer Maria Rilke or Goethe or Byron, poems from the 18th or 19th century still have the power to reach out and kick us and turn a light on our better, fiercer natures. We did vocal exercises that literally filled the actor’s body with the vibration of these strong words, so that the actors’ bodies became vibrating vessels for the poetry. Uncontainable.

Yes, I think you progress, but not in a straight line. The movement seems to be circular. The piece Revolution2 (1993-2003) intimates or draws this; it comes back to itself, but it also moves forward. We don’t always just need to leave a place or idea. We can leave it as a means to return to it.

AS: That first gallery you mention is really intense. A visceral energy comes through in pieces such as Whip Whipping the Wall (1998-2002) — where you are standing in a room and literally shredding through paint and sheetrock on a wall with a large intimidating whip, and Bim Bam (1999), where you violently slam doors repeatedly.

DF: The earlier works are angry, yeah, I was pissed! The actions are also displays of prowess… I wanted to smash and break through. I was concerned with not being seen or dealt with. This came from being in art school in Germany and the context there of being apparently invisible as a young woman making art. There was a desire to feel like you count and, and when no one seems to hear or see you… this feeling, you know, it doesn’t go away. Although it probably comes from a much earlier, much more indelible place. Like a sort of chronic gaslighting that young women have been trained to think is a norm, where your wishes and opinions are run over as if they were a speed bump, and you stand there blinking wondering what the hell just happened. It makes you want to whip off your wig or your face or body covering and scream, “Listen assholes, I’m here and I can see and hear and think and feel and love and I know things so for the love of god pay attention!” You know? Yeah, that feeling seems to be coming back. Which actually makes me smile. We’ll see how that goes…

AS: After leaving that first exhibition space there is a shift from you physically being in front of a camera to being behind it — where you engage different individuals (solicited) through casting calls, etc., as the subjects or catalysts of the films.

DF: It seems that I stopped filming myself after having children. I think that was simply because I was learning how to live with other people. You simply can no longer allow yourself to be so self-involved. So turning the camera on in a room by myself no longer jived with how I was living. Living with children, I had to train myself to anticipate the needs of others, as well as communicate my own. I had to learn to function as a group. And I think this fact of life simply mirrored itself in my art practice.

AS: You also started, to some degree, utilizing the public realm and (looking) beyond contained spaces, for the situations in your films to unfold. What drew you to use the streets of Miami as a context, as in Dancer3 (2011), rather than in an auditorium or studio?

DF: The studio, just like your thoughts and sense of self-worth, is contained within you. It’s not bound to real estate. Inside a person is the place that art making begins. The gallery, the museum, is the support structure often for manifested thoughts and feelings to be presented to others.The Public Art Fund became the support structure for the production of Musical4 (2007-2008), and then later Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, as a place to show it.

For me, I like quiet, so that I can hear myself think. And that can happen on the street. I look for a tension in the work. Like a type of tension illustrated by surface tension. You know when you have a little blob of water sitting on a smooth surface… It’s a liquid that for a moment exists as a blob, in spite of its nature, in a really fragile way, holding its shit together against all odds if you know what I mean. I look for that sense of strength in an artwork.

But you can do just about anything if you have support, if you feel that someone has your back. I’m the person who has the performer’s back when they are singing in the street, so that they can express themselves in an unguarded manner. And, of course, I also need support so that I can do that. It’s an entire chain link of support that links everyone together and becomes subject as well as structure.

AS: Is there something that interests you about creating a lived situation, where not every detail is intentional, but the work is taking place out in the real world?

DF: Basically, I would have to say that everything is intentional. Even what appears chance or random. That’s because a decision has been made to allow it to be chance or random. I am an editor. It’s is an incredibly controlling hand that can cut and frame the world into a very specific existence. Sometimes when I am editing and I don’t know where it’s going, it feels like raking mud. You rake, and then it oozes back into a muddy puddle. But then you keep raking and raking and raking and eventually out of the mud, a form manifests. And this too is the real world. Art is the real world. It is no more or less real that a stoplight, or a teacup, or an ocean wave, or a glance or a premonition. It’s all real and of this world.

AS: In the work Musical I have always felt a real sense of vulnerability in the performers. A kind of tenderness. These individuals are putting themselves out there, singing in the midst of crowded urban areas, such as Penn Station in New York, and absolutely no one cares. But you really feel them giving it all and you can see how brave each one of them is being.

DF: These were mostly students ready to put themselves out there. Many of performers had just arrived in New York City and were looking for a way to be heard, to feel themselves existing in the loud, crowded city. Coming raw with lots of desires and wishes wanting so much to be heard, to be seen, to be counted. There is a human need, and genuine strength and courage to be harvested, from giving voice, hearing yourself saying something good out loud and publicly. The ad that I posted for the casting said, “Come sing your song like you really mean it on the streets of Manhattan.” It’s simple, tender stuff…you know, like giving sincere compliments to strangers. When someone out of the blue, a stranger, says something very particularly kind to you, you put it in your pocket and carry it around with you for pretty much your entire life. It’s like a little shiny stone that you rub and makes you feel good. A powerful tender short exchange that lives and lives.

AS: It reminds me of when I lived in London as a student and I would go to open mics to sing.

DF: Exactly. Perfect medicine. In London, no one makes eye contact in the street. No one sees you. So it is as if you don’t exist. It can make you crazy if you’re not used to it. So an open mic, it helps that. Its like, I see you and hear you, therefore you exist. There is huge validation there, that tenderness and feeling in Musical perhaps contains that…is a witness to that.

If someone is lonely and wants to stop being lonely, they can make themselves porous and receptive to the world around them. If they want to attract someone or something, they have to first make themselves capable of receiving it. You’re not going to throw a ball to someone who has their hands in their pockets. Imposing, foisting your needs on someone isn’t going to work either. They’re just going to run away in the opposite direction as fast as they can. Rather than asking for something, if you are giving and open, this allows for a connection with others. Of course there have to be boundaries and rules. For me that’s why I like to have an open audition. The people who turn up to the audition are game and ready to meet you halfway. It’s a fair exchange.

Dara Friedman, Dancer, 2011. HD Black-and-white video transferred from Super 16 mm film, with sound, 25 min. Edition 1/5. (film still)

Dara Friedman, Dancer, 2011. HD Black-and-white video transferred from Super 16 mm film, with sound, 25 min. Edition 1/5. (film still)

AS: Though vulnerable, there is something different about Dancer. Would you ever use the word “generous” to describe that piece, the performers? They were not really performing for an audience, maybe for themselves, or for the city itself?

DF: I wanted Dancer to be electric, to share something I was carrying around with me that I wanted to pass along to others. Like hot-wiring a car, a jolt! I always go back to thinking about the Aesop Fable, The North Wind and the Sun,5 looking down at a man on Earth and making a bet between them who could get his jacket off quickest. The Wind says he can for sure do it, and blows and blows and blows. But the man simply hugs his jacket tighter against his body. Then it’s the Sun’s turn. And the Sun beams down warm rays on the man, and within a short moment he is quickly taking his jacket off. So yes, maybe that type of generosity is what you are feeling in Dancer. That type of energy that gets things to happen. If you want someone to pay attention, you have to show them how it’s done, by you yourself paying attention to what you are doing. In the truest sense, minding your own business.

AS: Is there something about being “game,” open to things, in the ways we have just discussed, that promotes an expression of freedom?

DF: In a game, the rules of the game evolve by playing. When we play, we exercise freedom, but within a context of respect. Rules are a little bit like laws. Some laws are created by nature. Other laws are created by people. If “people” can create laws and you’re a person, it means that you can make laws too. You are free to make up the rules to play your own game. If you want to play, it’s important to be game.

Dara Friedman, Perfect Stranger, at the Perez Art Museum, Miami, installation view.

Dara Friedman, Perfect Stranger, at the Perez Art Museum, Miami, installation view.

1 In Chrissy, Mette, Kristan (2000), three separately projected 16 mm color films play simultaneously on slot-loading 16 mm film projectors, each with optical sound and custom loopers and siting on mirrored plinths. The individual film loops repeat at 45 sec.; 14 sec.; 29 sec. In each film, a woman standing in front the camera rips open her blouse. As this happens, the sound of gunshots is played.

2 Revolution (1993-2002). A “young man walks along Washington Avenue in Miami Beach, at dawn. The camera keeps him in frame using a steady trucking shot. Meanwhile, the image tilts clockwise and continues to rotate until the world appears to have turned fully upside down. As this 360-degree revolution progresses, the horizon line rights itself. The film comes full circle and begins again.” – From the exhibition catalogue Dara Friedman, Perfect Stranger, as organized by Curator René Morales, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, page 114.

3 Dancer, 2007-08, HD color video, with sound, 48 min. Edition 2/5. “Sixty-six people of diverse ages and backgrounds, from classically trained ballerinas to pole dancers, tap dancers, clubbers, capoeiristas, calypso dancers, yogis, belly dancers, and tumblers – move through Miami, using the city’s sidewalks as a stage. The sound consists of sweeping musical medleys punctuated by the city traffic and the dancer’s breathing. The camera moves alongside each person’s body like a dance partner.” – From the exhibition catalogue Dara Friedman, Perfect Stranger, as organized by Curator René Morales, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, page 138.

4 HD color video, with sound, 48 min. “A total of fifty-five participants, selected by Friedman through open-call auditions, perform in the crowded streets and subways, diners, and plazas of Midtown Manhattan while singing a song meaningful to them at full volume.” – From the exhibition catalogue Dara Friedman, Perfect Stranger, as organized by Curator René Morales, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, page 128.

5 The moral of The North Wind and the Sun is “Kindness affects more than severity.”

Amanda Sanfilippo is the Curator for Art in Public Places of the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs and the Executive Director and Chief Curator of Fringe Projects Miami, a temporary, site-specific public commissioning agency.