© 2007 Sidney B. Felsen

This December a pair of Baldessari’s works commissioned by art collector and real estate developer Craig Robins as part of a series of permanent public artworks in Miami’s Design District will cover two façades of a new building designed by the IwamotoScott architecture firm and the Leong Leong design office. The works, titled Fun One and Fun Two are comprised of production stills taken from Baldessari’s extensive archive of found images, printed large-scale onto perforated metal and mounted to the sides of the building. The Miami Rail asked Nicolas Lobo to talk to John Baldessari about his soon to be completed commission, as well as other recent work and the often-made comparison between Los Angeles and Miami.

NICOLAS LOBO (RAIL): Hi John, thanks for taking the time to talk. I want to talk to you about the work you are doing for the Design District to be unveiled in December and also the work you recently showed at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow.

JOHN BALDESSARI: Well Moscow is not as recent but I’ll talk about it. [Laughs.]

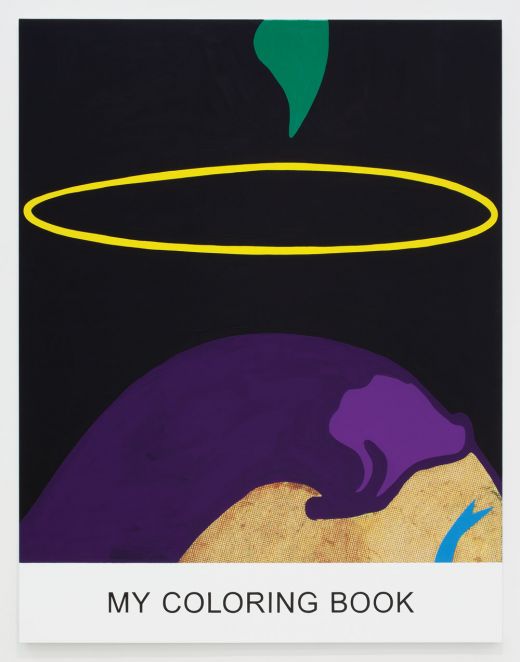

RAIL: O.K. great. In some of your canvases from the past few years you have been excavating paintings from art history to make new ones. I’m thinking about what you showed in Moscow. Often you allude to a kind of two-part experience. What is your interest in the double?

BALDESSARI: Well I guess I’d have to start all the way back when I was a painter. I gave up painting because it’s usually on a single canvas and it dawned on me that it implied there might be a single truth about something. I thought, well that’s not true. So I started using multiple canvases and moving into photography and using the multiple image. So that’s where it started. You know, I have an idea that you can’t understand black without white. One thing has to explain the other. So I always have to have more than two elements in my work.

RAIL: So two is the least amount while still having more than one?

BALDESSARI: Well, I have done single canvases but it’s image and text, so there are still two elements. By the way, the title of the exhibition in Moscow addresses the issue. It was called 1+1=1.

John Baldessari, Double Play: My Coloring Book, 2012. Varnished inkjet print on canvas with acrylic and oil paint. 84 3⁄4” x 65 3⁄4”. Courtesy of the Artist.

BALDESSARI: It’s a principal guiding idea in my work.

RAIL: So you stopped painting early on in the 1960s?

BALDESSARI: It was the mid-‘60s.

RAIL: Was it a gradual thing or did it happen all of a sudden?

BALDESSARI: Well I thought about it a lot and then I just decided I was on the wrong track. So one day I sent out notices to friends and anybody that I thought might be interested. I said come by my studio and I’ll give you any painting you want. Anything that was left over I turned into a ceremony or ritual for me and eventually had cremated in a crematorium. Then I had the ashes in urns, so it became a very formal event. I put a notice in the newspaper that I had done this and that was the end of it.

RAIL: Did you keep the ashes as a personal thing? Or was it work that ended up in a collection?

BALDESSARI: Well at first it was personal but then it got more and more public attention. I still have some of the ashes but some went to the Hirshhorn Museum I think.

RAIL: But you still use the canvas format, even now. The works shown in Moscow are printed images, but you stayed with a very classic canvas size and format, something very painterly. Why do you keep that aspect of painting in your work to this day?

BALDESSARI: Well you know when people see a stretched canvas they automatically believe it’s art, which is a complete fallacy of course. It’s so embedded in our culture. If there is a stretcher bar and canvas then it must be art.

RAIL: And you want your work to be instantly recognizable as art?

BALDESSARI: I would actually prefer that people say, “this is not art.”

RAIL: I feel like humor is another important part of your work, would you agree?

BALDESSARI: Well I’ve had other people use that word, I don’t think it’s humor like funny-ha-ha.

RAIL: What about in the Greek sense?

BALDESSARI: Well it kind of emerges. You know, I think a lot of the work of Goya is very funny, but I don’t think he was trying to make it funny. Maybe it’s more ironic or satirical or whatever. I don’t work with humor as a goal.

RAIL: But you enjoy a sense of satire?

BALDESSARI: Oh yes, of course. I don’t think anything is sacrosanct. I think art should stand on its own two feet, and if it can’t then it shouldn’t exist.

RAIL: So you’re not really comfortable with the word humor, but there is a certain something, I don’t know, a stance, an attitude that I called humor just now but it could have a different name?

BALDESSARI: That’s O.K. Whatever words other people choose are O.K. with me. That’s just the way it is. I just want to make clear I don’t have that as a goal.

RAIL: Do you think this attitude your work has is related to the place you come from—this California, or L.A. feeling?

BALDESSARI: No I don’t think so. It probably started way before Duchamp, but Duchamp is a reasonable enough person to bring up. You know, showing the urinal. Now I read that there are scholars who think he didn’t even do that piece, someone else did it.

RAIL: A certain R. Mutt?

BALDESSARI: Well, there’s the attitude that art is up for grabs. It’s certainly the basis of all of Warhol’s work.

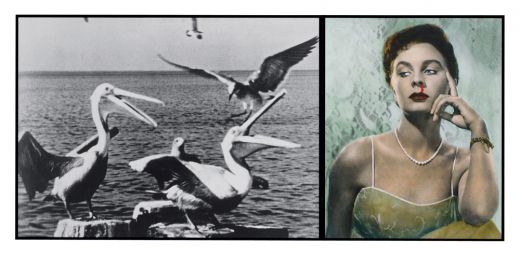

John Baldessari, Fun Part 2, (2004/2014). Image courtesy of the artist and Miami Design District Associates.

BALDESSARI: I think so. One comments on the other. I have to say the choice of finding imagery that I thought would work in Miami was kind of…you know. I was very aware of the situation so it had to be something dealing with the sun in some way.

RAIL: It’s funny that you bring it up, because I wondered if while you were choosing the images you had thought of the comparison between Miami and L.A. that is often made.

BALDESSARI: Yeah, well it probably helped. [Laughs.] You know, living in similar surroundings. The only difference is the temperature and the humidity, but other than that there’s not a lot of difference.

RAIL: That reminds me, I wanted to ask you why in these works for the Design District you did not include any colored elements or dots that have appeared in many of your other works made with similar images.

BALDESSARI: Actually one very small slice of one of the images did occur in a past work. Also I read a quote about me in a magazine where they said I’m going to be known as the guy that puts dots in front of people’s faces. So I wanted to get rid of that. I do other things too! [Laughs.]

RAIL: [Laughs.] That’s fair. In one image there is a kind of painted backdrop. I’m not sure if it’s a found image, or something you photographed yourself?

BALDESSARI: Oh no, that’s a film still that I also used as a beach towel. It seemed playful, and I thought people might like it in Miami.

RAIL: You often use film stills and present them as still images in your work. Are you drawn to film stills more than simple photographs?

BALDESSARI: Over the years I’ve collected them. They aren’t necessarily film stills, although sometimes they are. I guess the overarching term would be production stills. Pictures taken while a film is being shot and then used for press releases and that kind of thing.

John Baldessari, Pelicans Staring At Woman With Nose Bleeding, 1984. Silver gelatin print, color photograph and oil tint. 30 1⁄4” x 64 3⁄4”. Courtesy of the Artist.

BALDESSARI: Yes, there are two eyes there.

RAIL: Can you describe the quality that you like in them? Is it a slowing down of some kind? When you take an image of something that’s supposed to be seen in motion and then you kind of freeze it?

BALDESSARI: One could speculate and say that was the case, but a camera shooting at one-thousandth of a second is capturing motion. I see it as just another eye.

RAIL: I was looking at what you did with Mies van der Rohe’s Haus Lange, the brick house where you blocked out the windows and replaced them with ocean views. I thought that was interesting because you were working against the architecture and the ocean-view images were a pretty stark contrast to the actual view out the windows. Did you have similar ideas about working with the building in the Design District? How was it to work on such a large architectural scale?

BALDESSARI: Well I’m interested in architecture in general so anytime I get an opportunity to do anything I’ll do it. You know Frank Gehry is a very close friend of mine. We talk a lot, so maybe there is some influence there.

RAIL: When an artist and an architect talk about architecture, what kinds of topics come up?

BALDESSARI: Well I think we talk about everything but architecture. [Laughs.] The only time we talk about architecture is when we talk about the house he’s designing for me. But those are always very practical questions. You know Frank grew up in L.A. and was part of the art community and would go to the openings and he would know most of the artists. I think of him as a fellow artist that does buildings.

RAIL: Did you work with the architects that are designing the building your images will be displayed on in the Design District?

BALDESSARI: I don’t think we had any voice contact, but we had lots of e-mails back and forth. There was concern about how visible the imagery would be on the material they selected.

RAIL: It’s some kind of perforated metal, right?

BALDESSARI: Yeah, I hope it works. They reassure me that it will, but that’s all I can say at this point.

RAIL: To change the subject slightly, I wanted to ask you about education. I know you’ve spent a lot of your life teaching. I wonder how important you think it is for a city to have an educational framework for its cultural development?

BALDESSARI: Can you say the question in another way?

RAIL: Well, the schools you taught at in Los Angeles were very instrumental in the development of the kind of art that is made in Los Angeles today. Can you speak about that with regard to what similar things might or might not be going on in Miami right now?

BALDESSARI: I know at one time Craig Robins had an interest in starting an art school in South Beach and then for whatever reason, the discussion stopped. I don’t know if he is still thinking about that. I know there was a big meeting of art educators in Aspen at one point and they talked about it. And some people I recommended met with Craig in South Beach.

RAIL: So do you think it’s essential to have something like that in a city that is interested in defining itself culturally?

BALDESSARI: Yes, I think so. A lot of young artists today do go to art school, and do go to graduate programs. I think it’s good for any city and it has been very good for Los Angeles because a lot of those graduates are staying in Los Angeles instead of gravitating to New York.

RAIL: That’s a good case for it. Do you think the MFA system is ideal or do you see some other ways of doing it that are more effective?

BALDESSARI: Well I read every now and then of do-it-yourself art schools. You know, students get together and bring in artists to talk with them. It fulfills some kind of need as applied in the art field. But I think some other issues need to be addressed.

RAIL: You don’t seem so enthusiastic about the do-it-yourself school idea. What are those other issues that need to be addressed in an art-education environment?

BALDESSARI: Maybe I should clarify that. The good thing about them is that they are made of artists who invite their own artist-teachers to come. So I don’t see anything bad about it, I think it’s all good. Actually in the university system, I think what’s not good is having a set curriculum—one course following another course that one has to adhere to. And the larger issue—does one need an MFA to be an artist? It’s more and more in the air that you have to have an MFA to be an artist. I think that is unfortunate.

RAIL: Yes, I agree with you there. If I’m not mistaken you once said that art can’t be taught.

BALDESSARI: Yes, I still say that.

RAIL: But at the same time you taught art for many years, so I wonder what it was you spent your time doing.

BALDESSARI: What I tried to do when I was teaching was to make sure there were a lot of artists around who could serve as role models that the students could talk to, so they could at least find out what other artists think art is.

RAIL: So a facilitation of people who would become artists regardless?

BALDESSARI: Yes, you get to talk to somebody who does something you have decided to do. There is a kind of teaching going on there but I don’t know if you’re teaching art. I have no idea how to teach art.

RAIL: That’s a winning quote I think. Anything you would like to add on the subject of Miami or otherwise?

BALDESSARI: I think Miami, certainly South Beach, is becoming more and more important on the international art map. And I think that’s terrific for Miami.

RAIL: What was it like to see Los Angeles become important as an art city?

BALDESSARI: Well it’s a slow process. It’s like the lobster being boiled in hot water. Does he notice the water getting warmer? Not really. [Laughs.]

RAIL: [Laughs.] Well you’ve just answered my next question but I’ll ask it anyway. Are there any particular turning points in that process, where you kind of took notice and thought, aha! Either for yourself or what you saw going on in the city?

BALDESSARI: I think you start noticing that more artists are staying in Los Angeles and are not going to New York. You see more galleries moving in. You’re aware that something is happening.

RAIL: So what do you think are some of the best ways people in Miami can participate in that kind of network?

BALDESSARI: The people in Miami I’ve met are doing a pretty good job making spaces to show work and having programs that are open to the public, bringing in guest speakers. So yeah, I think it’s terrific.

Nicolas Lobo is an artist living and working in Miami. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, he also produces radio programs and has published three artist books on the subject of sound and culture.