PIONEER WINTER: IN PROCESS

CATHERINE ANNIE HOLLINGSWORTH

Pioneer Winter in rehearsal with sandbags, 2015.

Winter’s investigation is tentatively titled Host. As in: host of a party, guest, or disease. The title implies a dynamic relationship between a self and other(s), with one often imposing its will on another. According to Winter, a primary conceptual foundation of Host is that of the panopticon, the imagined prison architecture proposed by British social and political reformer Jeremy Bentham and later appropriated by French philosopher Michel Foucault to describe a mechanism of social control in which individuals self-censor because they believe they are under constant surveillance. In this context, “host” might describe the bodies of governed subjects that have been invaded by systems of authority.

Winter’s references to the panopticon are loose. In discussing his choreographic process, he talks about separate seeds of ideas he calls “images.” For him, this primarily visual mode connects in some way to the panopticon, which functions specifically through lines of sight. Thus far, many of the images also involve one body interacting with and/or controlling another body. In theory, he is looking at social systems through bodily relationships, asking how control is applied and enforced.

In our recent phone conversation, Winter described one of his first images of Host, an exercise between two dancers:

First, I took two women and I gave them both different directives. I told one woman, “Move across the room.” And I told the other woman, “Don’t move, don’t allow yourself to move.” So two people with conflicting goals are basically trying to outmaneuver each other physically.

Another similar image involves the application of physical weight:

I took four twenty-five-pound sandbags and I strapped them to different parts of my body. And I tried to move with the same fluidity. How do I find the ease in this discomfort? How do I negotiate this new weight? Can I shift all one hundred pounds to my right arm so that my left arm and my left leg can be completely free? Do I switch it to my left foot so that my arms and my right leg are completely free, but I’m just planted and I can’t move?

Other images are less about control and more about relation- ships, described through bodily negotiations:

Imagine yourself standing in front of someone. You may be a foot apart from the other person, and your eyes are closed. And you can only move when you feel the other person moving and they can only move when they feel you about to move. And you move centimeters at a time because that is the desired behavior, that you don’t move until you feel the acquiescence of the other person. And you sort of go through this progression until you’re touching. And you get closer and closer until you’re in a sort of embrace.

Each image is subjected to an excavation that Winter calls “image weathering,” in which he approaches the feeling state of each image as a way to uncover its core. He works on multiple images simultaneously rather than progressing through one image at a time, describing his vision of the final product as a viewfinder, with multiple lenses or slides. Alternately, he imagines a kind of collage of disparate elements that have been cut and pasted, rotated, or layered, with themes formed mostly by spatial or temporal association.

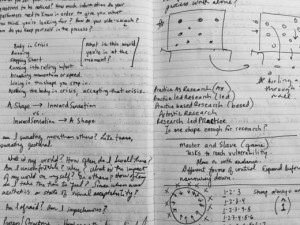

Pioneer Winter’s choreographic notes for Host

Winter currently considers Host as a critique of the panopticon, which he describes as a faulty system of governance because it imposes on the mind but ultimately fails to act upon the body:

My argument is that since the body at its flesh state, mechanical state, emblematic state, is unconscious of the restrictions placed upon it by the panopticon, only our mind is really aware of our restrictions. . . . You could argue that the body is free of the instrumentation of the panopticon.

This statement describes a mind/body split, claiming that control can operate on one aspect of human embodiment without the other. But overall, in its sketch form, Host contains multiple and sometimes conflicting articulations of control over mind or body. In some images, control might be applied directly from one dancer’s body to another, mimicking brute force. Other images rely on verbal cues aimed at the mind, or emotional state of the performer, duplicating systems of control that manipulate subjects without any reliance on physical enforcement.

Similar questions are also surfacing in the choreographic process itself. Winter asserts that his dancers are more than just technically proficient bodies. They are creative collaborators who tap into and move from their own autoethnographic experience under his direction. His cues are intended to recreate the feel-

ing state contained in the images, within their bodies. He also uses choreographic methods that call on dancers to access their own memories of people or places, and to respond physically. Simultaneously, he claims that dancers do not use their bodies, they are their bodies, and they are at their best when they can embody their personal stories beyond the reach of the mind.

At each level of investigation, it seems impossible to really separate the mind or the body as a target for control. Further, systems of control appear to be ever-present, even in the choreographer-dancer relationship. Winter is aware of the ambiguities embedded in Host, observing: “I’m critiquing the panopticon and the way it makes certain assumptions about human beings. But I’m doing that with the scenography myself. I think it’s systemic.” As a dance work, Host need not resolve questions of control. The key is whether his audience can engage with the ideas at play.