Culture Brokers

Ahmed Mori

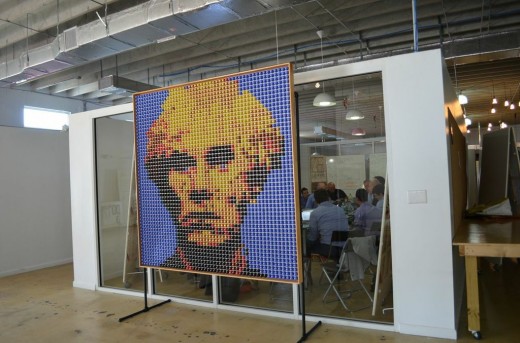

Portable work stations at The LAB Miami. Photo courtesy of The LAB Miami.

“I think entrepreneurs ARE artists, so is anyone who does human work, work that might fail, work that connects us.”

—MARKETING GURU SETH GODIN, IN AN EMAIL WITH THE WRITER.

It was a utopian scene. More than 80 folding chairs faced a chalkboard adorned with multihued verses as coworking campus The LAB Miami hosted a Friday night poetry and ballet commission as part of the O, Miami Poetry Festival. Tables of complimentary wine and desserts flanked Minerva Cueva’s égalité mural, a defaced Evian ad profiling the archetypal French revolutionary adage, the peer-progressive slant of which mirrors The LAB’s goal: to provide an urban home for a very mobile creative class. The crowd is worlds away from the Miami of reality-TV lore, marked by subdued perfume scents and less discernible accents. One attendee utters muertos de hambre, which in local Spanish describes the young man coding away in his laptop in the third row or the group of girls jotting down thoughts on their iPads.

Although “muertos de hambre” roughly translates to “starved to death,” it’s not typically pejorative, at least not in this particular case. Here its use moves beyond the charming celebration of gluttony portrayed in a “shit abuelas say” video, instead typifying economic stereotypes that underscore the cultural contradictions to which the city owes its fame. Traditionally, Miami has been dominated by suntan lotion and tower cranes, a stark contrast to the region’s much-lauded upswing in cultural-industry initiatives. More precisely, the mostly private cultural ventures operating out of South Florida represent a $1.5-billion-dollar economic impact that institutions like The LAB Miami want to capitalize on as they help fill a large vacancy in coworking ventures. A model where independent workers rent space or pay membership fees to work on projects, business efforts or contract work, coworking, because of its social nature, has become synonymous with collaboration, community education and overall entrepreneurial bustle.

“We really just wanted to solve the challenges Danny [Lafuente] and I were facing,” said Wifredo Fernandez of co-founding The LAB Miami. After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania a few years back, the two childhood friends figured they’d swim against the brain drain and set up shop in their hometown again. But without the resources they envisioned—talent, access to capital, mentorship and a professional setting where they could work and hold meetings—they felt limited vis-à-vis other urban centers across the country with cushier homes for the creative class. The dynamic almost hampered their future partnership. Case in point: while Lafuente returned to direct communications efforts at the Cuban American National Foundation, Fernandez spent time in Washington, D.C., completing the Teach for America program and attending seasonal educational seminars at the Institute of Design at Stanford.

Nevertheless, the two kept up closely with the progression of Miami over the last half-decade: the growth of Art Basel Miami Beach, the patronage of the Knight Foundation, and jumpstart initiatives like local web and tech meet-up Refresh Miami, business accelerator Incubate Miami, and the community-building Launch Pad at the University of Miami. Building off the momentum of these components seemed like a winning formula, they felt, and the team took an interest in marrying the city’s art scene and creative genius to its burgeoning tech talent.

Wynwood’s rise as the one of the country’s hottest critical masses of cultural businesses and institutions made Fernandez and Lafuente’s decision to pack up the moving truck a tad easier. Inspired by the experimental nature of the arts district, they slapped LAB onto the project and constructed a prototype in June 2012, a 700-square-foot space with custom-built tables fashioned from a $300 trip to Home Depot. To the team’s surprise, the space very quickly became a kind of honeycomb, carved out by a mix of techies, creatives and small nonprofits. The LAB’s success led to considerable event planning—programming classes, art exhibits with gallery-level organization, small-scale conferences, hacker meetings, educational seminars and guest lectures featuring prominent entrepreneurs from every corner of the country.

This influx of activity caught the Knight Foundation’s attention, whose funding helped spearhead the team’s transition to a new home beside the Light Box in the Goldman Warehouse. The transition was marked by a change in the LAB acronym: “love, art, business” surreptitiously became “learn, act, build.” With fourteen times the floor space, furniture by Emmett Moore and the work of local artists like Fabian De La Flor, The LAB proves itself to be more accommodating as “a hub for the creative class,” according to Fernandez. “We studied what Richard Florida [urban studies theorist and author of The Rise of the Creative Class] was writing about. Miami has these people. We know they exist in isolated pockets. So we tried to build a platform that could bring them together. It’s about people finding their tribes.”

By April 2013, The LAB member count hovered around the 80 mark, comprised namely of programmers, investors, nonprofits, a landscape architect, a photographer and some graphic designers who pay a monthly fee to access a desk and a meeting area. Participants in the growing “maker” community, a DIY subculture where engineering-related interests such as electronics, robotics and 3-D printing are embraced, have also taken a particular liking to the campus. This is exemplified by Makeshop Miami, a LAB member and the space’s first incubated business project.

Founded by Michigan-transplant Tamara Wendt and Karja Hansen and Matt Lambert, two alums from the Duany Plater-Zyberk & Co. architecture firm, Makeshop is a fellow coworking cohort awaiting the completion of their “makerspace” in Little Havana. The fully outfitted studio space will accommodate high-tech electronics projects, while also offering equipment for working with textiles, ceramic, wood, metal and even food. And like most maker communities around the country, the group will offer education and training in subjects like 3D printing, providing a public-facing hub for hobbyists to transform passion and curiosity into profitable skills and world-changing exploits.

Photo courtesy of The LAB Miami.

Lafuente’s prediction doesn’t seem so far-fetched in light of a 2012 Bureau of Labor Statistics report, which estimates 40% of the workforce will be self-employed by the end of the decade. In turn, both parties’ belief that upending traditional models of work will help define the future of the city’s economic well-being is especially significant for the success of the cultural industries, whose livelihoods depend more on collaboration than on copious amounts of coffee and the latest Macbook. If Art Basel and driving through Wynwood weren’t already enough evidence, a market study conducted by Americas for the Arts last year reported that Miami-Dade County arts organizations were directly responsible for 17,951 full-time-equivalent jobs in 2010, and almost double that number when taking into account the economic impact of both local and foreign audience attendance.

It’s appropriate that Fernandez and Lafuente see The LAB as an application programming interface (API), a computer language and message format allowing software applications to “talk” to each other. They envision The LAB as a platform where members of the city’s cultural industries “connect and collide.” The swift rise of a large-scale collaborative work-learn space indicates that the nature of work in Miami could be changing, bringing about a spike in collaboration high enough to alter how projects and entrepreneurial ventures raise money.

Not to mention, headquartering talent a la The LAB increases investor confidence—angel, seed and Venture Capital funding is less risky in the presence of creative or tech talent. And since coworking spaces are usually a for-profit venture, The LAB’s success is important to the local economy on two levels. “People pay and spend a lot of money and time at networking events around the country, but the place you go to should be an all day networking activity,” says Wendt. “It’s community – it’s for the people who are out there on their own, freelancers, small businesses, etc. I think The LAB is really capturing that here.”

Photo courtesy of The LAB Miami.

Seeing as community-building is the common denominator for success among profitable coworking spaces, the successful few help build a city’s foundation for entrepreneurial vim. Now as Miami flaunts its cultural capital, it cultivates the qualities needed to breed, lure and retain creative types, aiming to ultimately incubate innovation. But an Atlantic Cities study this year revealed the region’s creative class still hovers just below the national average, meaning Miami could use all the coworking hatcheries it can house.

So do The LAB’s collaborative successes make the space a model for the future of cultural ecosystems in Miami? Hector Garcia, serial entrepreneur and co-founder of The Hangar, a Wynwood-based gallery/artist agency/educational space, blames any foreseeable roadblocks on the Miamian persona, the “egocentric team-of-one” attitude he believes drives cultural mentors away from engaging their community. “We need to find a way to make [initiatives like The LAB] permanent, find a way to keep them independent, while making sure they’re fundamental staples of Miami culture,” remarked Garcia.

“It’s important to find leaders, someone to lead an initiative.”Garcia suggests a triangular approach to advancing Miami’s cultural industries: the talent (say, an artist or fashion designer), a publicist-like figure capable of “making moves,” and an investor-mentor with expertise within the field in question. The last of these is a conduit between the talent and additional mentors, e.g., more established artists or designers.

Now The LAB isn’t the first coworking space in Miami, of course, but it’s the kind of cultural playing field capable of engendering partnerships like Garcia’s triangle. Their committed datamosh of artistic events, educational seminars and creative coworkers may seem easy-going and spontaneous at first glance, but no cultural bacchanal goes uncoordinated. Potential businesses and independent workers apply and a membership committee evaluates how well a candidate will fit in with the space’s culture, ensuring less competition in favor of increased collaboration.

This curated approach provides the membranous habitat entrepreneurs and artists thrive off, and it’s visible throughout. One look at Fernandez’s getup—a tailored sport coat paired with paint-stained chinos—or catching wind of Lafuente’s acting chops gives credence to educationalist Sir Ken Robinson’s notion that we’re educated via our own creativity. As a result, Fernandez and Lafuente’s LAB embodies an unapologetic embrace of a changing city culture, which makes it more of a nerve center for the tech and cultural communities than just another alternative to the cubicle or coffee shop. The LAB is a catalyst as much as a reaction, an effort to fill a void in a city with vibrant energy but few conductors.