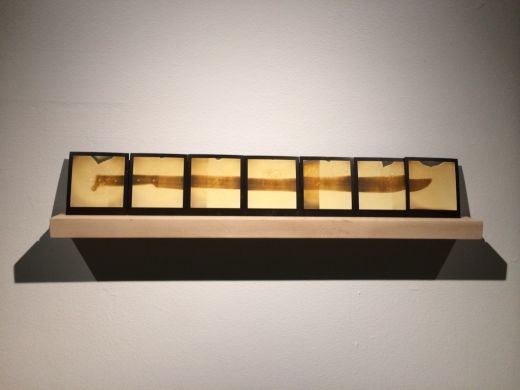

William Cordova, untitled (narratives), 2011-2014, Polaroids on custom Ceiba wood shelf.

May 22 – July 12, 2014

Swing/SPACE/Miami

In the catalogue for William Cordova’s fleeting and detritus-fueled exhibition at Swing/SPACE/Miami, the artist reprints an excerpt from Towards a Third Cinema by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino:

“Each projection of a film act presupposes a different setting, since the space where it takes place, the materials that go to make it up and the historic time in which it takes place are never the same. This means that the result of each projection act will depend on those who organize it, on those who participate in it.”

The exhibition is a loose, drifting assortment of stories: that of freed slaves, diary excerpts from the artist’s life, even a short story by a Cuban science fiction writer. But it is the viewer who, in sifting through the work, makes new connections, and constantly contributes more tales.

You first see a machete hacked into a row of seven polaroids. Each image is yellowed and distorted by bubbles, which is fine because everyone knows that polaroids are never just about image quality, but about image physicality: the weight and feel, the thing of the image. To take a polaroid isn’t just to preserve a moment, but to listen to that coital grind as the exposed film spews from the camera mouth like Gene Simmons’ tongue. That Cordova is interested in all of this ancillary experience, time and touch-based, becomes clear as one moves to the next room. In a darkened chamber, two slide carousels on the floor project two images.

On the left: coastal scrub, what was once Fort Mose, near St. Augustine, Florida. It’s the type of photograph taken to remind the photographer that they’ve been there, as opposed to announce the place, in the form of a postcard or a landscape photo, to others. It is shot quickly, almost as an afterthought, to aid later memory. The photograph on the right is denser, with more green and less sky. We feel like we’re intruding on both of these photographs. On a nearby wall a vinyl record contains ambient sound taken from the sites. Cinema haunts this installation, not only because the projected image. The title of this piece, Sculpting Elsewhere in Time (fort mose, st. Augustine, fl/ceiba mocha, Matanzas, cuba) 2012 nods to Andrei Tarkovsky’s book on cinema. The parenthetical, however, attends to the social and political history which Cordova revisits.

Fort Mose, a few miles from St. Augustine, was established in 1738 as the first settlement of free blacks in what would be the United States. At that point, the land still belonged to Spain, which had offered refuge to slaves escaping from English colonies. After the Fort was wiped out by General James Oglethorpe (the man who founded George as a debtors colony), the inhabitants went first to St. Augustine, and then eventually to Ceiba Mocha, Cuba.

Installation view

Another of which lies behind the final wall, projecting an nondescript yet evocative image into a small wooden box. It is a picture of a street with trees that stretch up and over the single automobile parked there. It’s an old car, 1940s maybe, such are the curves of the wheel wells and hood. In the middle is a burnt-out hole. Not black and charred, just white. Off to the side is another turntable, containing a recording o Miami poet Lela Lombardo reading a short story by Cuban writer Ivette Vian. The work, like the exhibition, splices many different strands of meaning, but is most touching when they slightly unravel.