Plaster model of the finished Pietá in the artist’s studio, South Bend, 1956. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

Plaster model of the finished Pietá in the artist’s studio, South Bend, 1956. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

ACT I: THE LETTER

His Excellency

Archbishop Joseph P. Hurley

Bishop of St. Augustine

40 Cathedral Place

St. Augustine, Florida

Your Excellency,

Although I have not had the pleasure and honor of meeting you personally, I am writing you in a matter concerning Cardinal Stepinac. We are both concerned about his fate, you as a high dignitary of the Roman Catholic Church, and I as a Croat and a Catholic. As Regent of the Nunciature of the Holy See in Belgrade you were present at the trial of Archbishop Stepinac. You saw his bearing during the trial, and you know the reason and the purpose why Stepinac was “tried and found guilty.”

My countrymen, priests and lay, together with other citizens of this freedom loving country are preparing in Detroit, Mich., in October, a manifestation for Cardinal Stepinac which will be at the same time a protest against the persecution of the Archbishop of Zagreb and the Church in general. The organizing committee has written you and has invited you to attend this manifestation. They asked me as a friend of Archbishop Stepinac to write you and request that you give an affirmative answer to their invitation. I am doing this hereby.

Your excellency has undoubtedly heard about the newest barbaric attacks on the Bishops and priests in my homeland. You certainly feel that it is urgent, both for religious and humane reasons, to renew the protests against these attacks on freedom, and to unmask the communist lie that there exists “religious freedom” in Yugoslavia. With this lie the Yugoslav regime is trying to fool the public opinion of this country.

I am certain that you will accept the invitation to go to Detroit if you find it possible.

Sincerely yours,

Professor Ivan Mestrovic

OCTOBER 10, 1953

Professor Ivan Mestrovic

817 Livingston Avenue

Syracuse, New York

Dear Professor Mestrovic,

I hasten to send you this message of cordial thanks for your gracious invitation to attend the manifestation in Detroit in honor of Cardinal Stepinac and in protest against the persecution of the Church in Croatia. Your invitation is all the more appreciated since it comes from one of whom I heard so much during my stay in your beloved country and whose great artistic creations I have viewed with so much pleasure and profit. It is my hope that some time when I am in the neighborhood of Syracuse I may have the happiness of visiting you and coming to know one of Croatia’s greatest sons.

My regret is great indeed that circumstances compel me to decline your kind invitation. . . . [B]ecause of my past position as Papal Legate in Belgrade, diplomatic proprieties oblige me to abstain from all public pronouncements about that country. You will, I am sure, understand that my usefulness to the cause which we both love might be impaired if I were not to hold scrupulously to the proprieties of my positions. I am confident, too, that you and your confreres will respect the request which I now make that my name be not used in connection with the religious persecution now raging in Croatia. You may be sure that the Holy See and the Church in America will miss no opportunity to alleviate the lot of your heroic people who once again are gloriously justifying their age-old title as “antemurale Christianitatis.”

Believe me when I assure you that my own services to the common cause will be greater if I am allowed to work in the manner which is permitted to me by all the circumstances of the case.

With sentiments of high esteem and of cordial personal regard, I am, my dear professor,

Very sincerely yours in Christ,

Joseph P. Hurley

Archbishop,

Bishop of Saint Augustine

So began the relationship between Ivan Mestrovic (1883–1962) and Joseph P. Hurley (1894–1967), two quietly towering figures whose unwavering engagements with faith and its preservation in the postwar order both distinguished their entirely singular careers as well as displaced them from the annals of their respective histories. One, perhaps the greatest sculptor of religious themes since the Renaissance, modeling Biblical scenes at a moment when critical trends ensured such work would find little standing in the modern canon; the other, an officer of the Catholic church, called upon as diplomat and intelligence asset by two sovereign states whose fluid policies repeatedly placed him at odds with both the US State Department and the Holy See. Though molded by starkly different conditions, duty and circumstance eventually (if only briefly) brought their lives into alignment. (FIG 1)

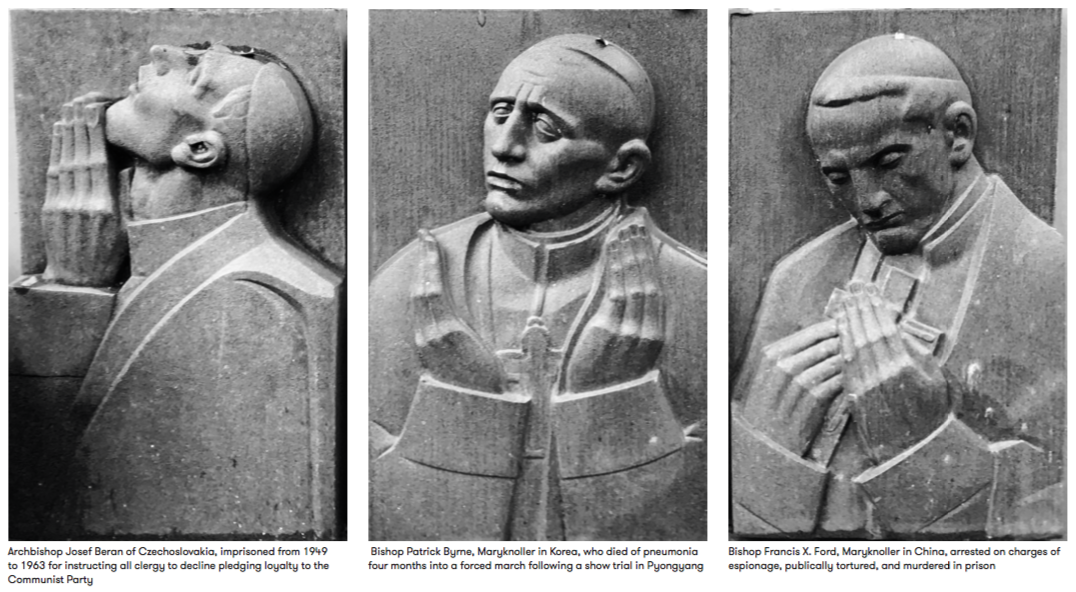

For the City of Miami, this affiliation culminated in a rather exceptional memorial project: the shrine to Our Lady Queen of Martyrs, a sculptural suite honoring “those who suffered for the Faith in the great Communist persecution of the twentieth century.” Twice relocated before its installation in a highly modified form at the Archdiocese of Miami’s Pastoral Center in Miami Shores, the memorial consists of an over-life-size bronze Pietà and six granite portrait reliefs showing victimized prelates after the fashion of saints. In aggregate, the work contends with some of the most fundamental dilemmas faced by any person of faith in the modern era who wishes to reconcile the demands of the spirit and those of the flesh; of church and of state; of the individual in society; of the present moment as it collides with the eternal.

While the relationship between Mestrovic and Hurley may have seemed to outside observers classically that of artist and patron, their correspondence reveals a far more intimate fellowship. Each found in the other a wellspring of hope that the human spirit might yet emerge intact from the catastrophic first half of the twentieth century. References to the commissions for the Florida diocese are almost inconsequential in the arc of the eight-year exchange. Expressions of sincere admiration and updates on bronze casting are punctuated by numerous entries with confidential! penciled at the top, each returning the conversation to a mutual concern: the fate of the Croatian church under Communist rule and, most particularly, the case of Cardinal Aloysius Stepinac.

FIG I From left: Ivan Mestrovic, Joseph P. Hurley, and unidentified priest (possibly John P. McNulty). Saint Augustine, 1955–58. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

FIG I From left: Ivan Mestrovic, Joseph P. Hurley, and unidentified priest (possibly John P. McNulty). Saint Augustine, 1955–58. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

Cardinal Stepinac, Archbishop of Zagreb, remains a deeply controversial and polarizing figure. In many ways he encapsulates the broad range of conflicts that have long beset the Balkans—struggles for independence and self-determination, the entanglement of religious and national identity, and ethnic violence, to name only a few—and that came savagely to the fore in the twentieth century. When in 1941 Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy appointed the ultranationalist Ustaše movement as governing party of a nominally independent State of Croatia, Croats who had long yearned for national sovereignty were faced with a decision: embrace the repressive new regime, which under the banner of Catholic Nationalism systematically slaughtered Jews, Serbs, Roma, and political dissidents; or abandon, at least for a time, the dream of a self-governing Croatian state. Mestrovic, a devout Catholic who had been active in the Yugoslav independence movement and who had devoted much of his creative energy to patriotic themes, chose the latter. He was arrested soon after the Ustaše rose to power and held for five months in Savska Cesta prison before extended negotiations with the Vatican secured his release to carry out a series of commissions in Rome and thereafter remain in exile. No doubt Stepinac, a close friend of the revered artist, played a central role in these proceedings.

Stepinac’s own positions during the war years were decidedly more equivocal than his friend’s outright opposition. He adhered to the official Vatican policy of “impartiality”—the preferred term for neutrality and nonalignment—neither openly embracing nor condemning the new regime; tacitly supported new race laws restricting the rights of Jews and Serbs, though opposed the program of extermination; welcomed prohibitions on education and behavior that deviated from the most conservative interpretations of Church dogma, but dissented in the matter of forcibly converting Orthodox Christians; quietly critiqued specific policies while supporting the national agenda in general terms. In other words, while certainly not guilty of all accusations leveled at him in 1946 by the courts of the now-unified and communist Yugoslav state, neither is it clear that the he was entirely innocent. Nevertheless, Stepinac’s trial, conviction, imprisonment, and house arrest became a cause célèbre for American Catholics and Croatian émigrés, who even before the Archbishop’s death in 1960 had come to view him as a martyr for the faith against the march of atheistic communism.

Observing the trial of his friend and other developments in Yugoslavia, Mestrovic rejected a personal invitation from Marshal Josip Broz Tito to return to his homeland, instead moving to the United States to accept a position as Professor of Sculpture at Syracuse University. It was from here that he penned his first letter to Hurley regarding the planned manifestation in Detroit. Though the two had never met, each was well aware of the other’s stature: Mestrovic, the internationally renowned artist and heroic son of Croatia, whose actions and opinions held immense sway in his homeland.; and Hurley, a Vatican diplomat and occasional asset of the US State Department, whose clandestine activities against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy found him banished to the apostolic backwaters of Florida before being elevated briefly (1945–49) to the position of papal regent of the apostolic nunciature in Belgrade. The two men remained close well after the completion of the Florida commissions; after all, as Hurley wrote late in 1961, in “matters which are close to our hearts. . . . We have so many things in common.”

ACT II: THE COMMISSION

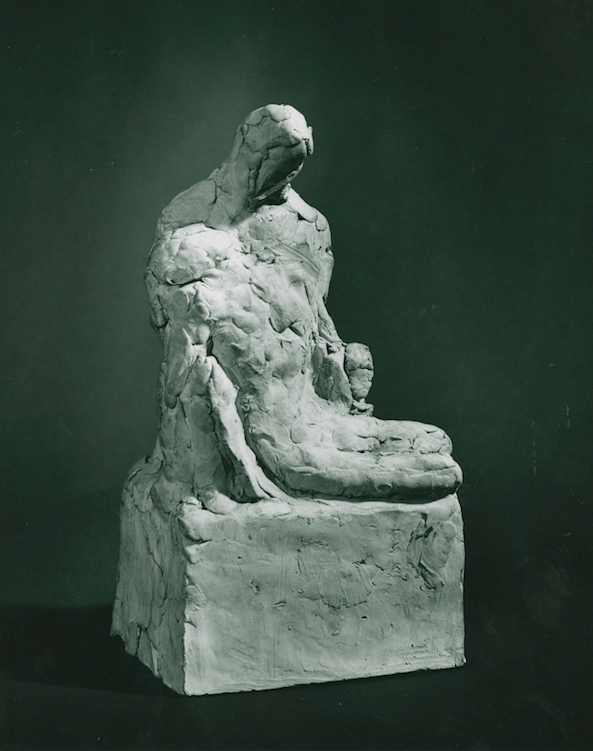

FIG III Plaster model of the finished Pietá in the artist’s studio, South Bend, 1956. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

FIG III Plaster model of the finished Pietá in the artist’s studio, South Bend, 1956. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

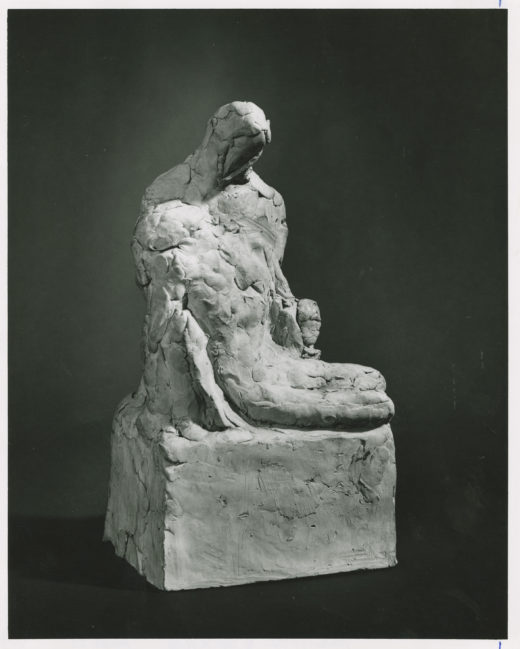

FIG II Preliminary study for the Pietá, 1955–56. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

FIG II Preliminary study for the Pietá, 1955–56. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

On September 18, 1954, Mestrovic received a letter from Monsignor John P. McNulty, secretary to Hurley at the Belgrade nunciature and after, inviting the artist to carry out two statuary projects for the Diocese of St. Augustine, which at the time oversaw church activity for the entire state of Florida. The first was for a memorial in St. Augustine dedicated to Padre Mendoza de Grajales, the Spanish priest who established North America’s first permanent mission, Nombre de Dios. The second commission—the one that interests us here—concerned the planned shrine to Our Lady Queen of Martyrs, which was to be built on a site in Coconut Grove adjacent to Mercy Hospital and Immaculata Academy (now Immaculata-La Salle High School). McNulty visited Mestrovic in Syracuse in early November, and by the end of the month Mestrovic had outlined his conception for the shrine:

As regards the monument to the Queen of Martyrs . . . it seems to me that the best solution is to be found in a Pietà, i.e. the figure of the Holy Virgin holding the limp body of Her Divine Son. In view of the fact that this group would stand in the open it should be given, to my mind, a background to give it prominence and a sacred appearance. On this stone background, in the shape of a semi-circle, I would suggest that portraits of the most prominent contemporary defenders of and martyrs for Christendom should be incised.

The pedestal for the Pietà, as well as the background wall, would be executed in granite or another hard stone to give the impression of durability amidst the fleeting passions of the modern world. Mestrovic began modeling the Pietà in clay (FIG II) in 1955 following visits between St. Augustine, Syracuse, and Notre Dame (where he was now a Professor of Sculpture), during which the artist and Hurley clarified the overall plan for the shrine. By April 1956, the plaster model of the grouping was complete (FIG III) and by the end of August was en route to a metal foundry in Rome. The bronze casting arrived in Miami one year later.

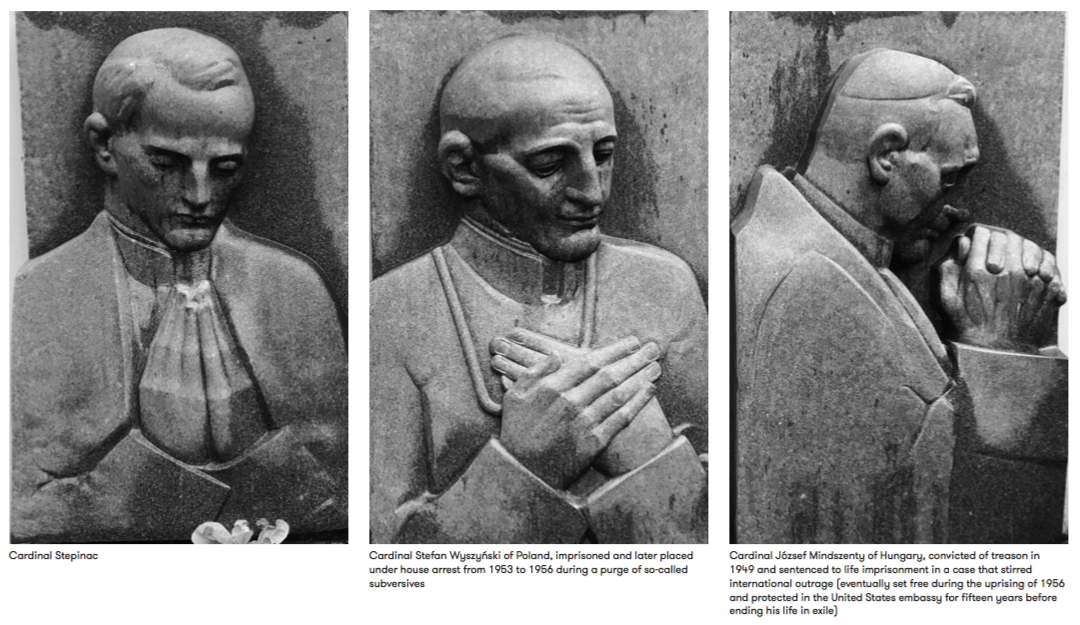

In the meantime, work on the relief portraits began. Hurley personally selected the six figures to be represented:

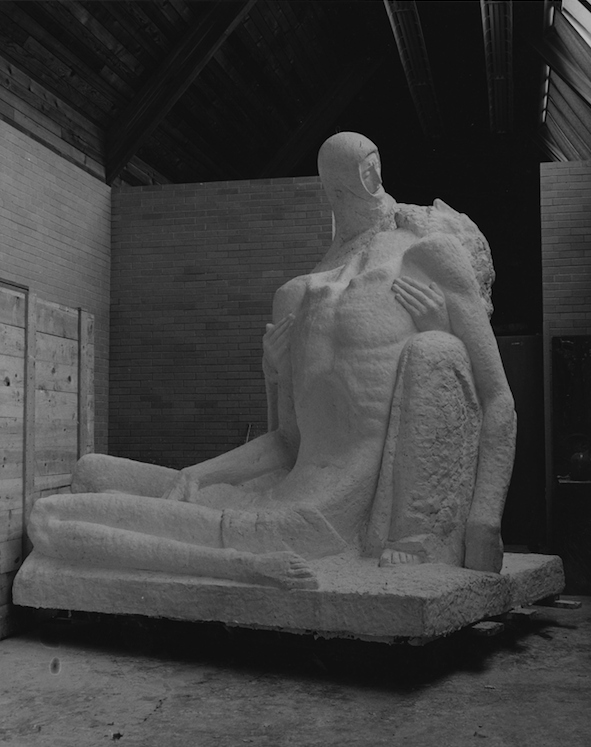

FIG IV–V Views of the unfinished shrine to Our Lady Queen of Martyrs, near Mercy Hospital

FIG IV–V Views of the unfinished shrine to Our Lady Queen of Martyrs, near Mercy Hospital

and Immaculata Academy, Miami, 1958–59. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

ACT III: THE REVOLUTION

FIG VI View of the Pietá at Our Lady of Mercy Cemetery, Doral, c. 1978. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

FIG VI View of the Pietá at Our Lady of Mercy Cemetery, Doral, c. 1978. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

From 1940 through the 1950s, Hurley showed himself to be an astute investor in the Florida real estate market, purchasing thousands of acres throughout the state and amassing a portfolio that by 1954 exceeded in value the capital assets of many of the Sunbelt’s most successful banks. When Vatican officials announced (without consulting Hurley) that Florida would be divided into two territories, Hurley received orders to transfer to the new Diocese the deeds to all church property in the state’s southernmost sixteen counties. Owing to postwar population trends, the undeveloped parcels in South Florida were far more valuable than the portion of the portfolio situated in the north. Hurley defied the order that he sign over title, setting up a land dispute that would last for the next seven years; it began in 1959 when the Archbishop set up a holding company (the Catholic Burse Endowment Fund) to receive ownership of the contested properties on behalf of the Diocese of St. Augustine, and ended in 1965 following the convocation of three separate Vatican commissions and threats to Hurley’s status in the church. The following year, Coleman outlined plans to construct a shrine to Our Lady of Charity, honoring Miami’s Cuban refugees, on the waterfront site then-occupied by the unfinished shrine to Our Lady Queen of Martyrs.

Whether or not personal hostilities had a hand in the dismantling of Hurley’s memorial project, the fate of bishops in Eastern Europe and East Asia certainly seemed ever more remote in light of the new Cold War front that had opened not far from Miami’s shores. Under Coleman’s leadership, the Diocese of Miami played a central role in receiving the waves of exiles that came to South Florida in the wake of the Cuban Revolution. It was only appropriate that the local Catholic community erect a beacon of solidarity with its sisters and brothers still suffering across the sea. And yet Coleman’s call that it be erected on the site previously slated for Mestrovic’s Mother and Son and modern Martyrs can hardly be viewed without suspicion.

The Pietà was removed from its pedestal sometime between 1967 and 1972 and relocated to Our Lady of Mercy Cemetery, overlooking construction of the Florida Turnpike Extension. (FIG VI) The reliefs likewise moved west to the cemetery, where they remained in their crates until sometime around 1981, when they reportedly were unpacked for installation inside of a mausoleum chapel. (FIG VII) The entire suite of sculptures moved once again in 1983, installed together for the first time in the garden of the Archdiocese of Miami’s Pastoral Center in Miami Shores. The reliefs are mounted in groups of three directly on the two flat walls to either side of the Pietà, which itself is elevated and facing Biscayne Boulevard—hardly the arrangement Mestrovic and Hurley originally envisioned. Years of exposure to the subtropical salt air has taken a severe toll on the bronze; surface corrosion abounds, in some places giving way to deep cracks and deterioration. The Diocese is currently in the process of developing a conservation plan. Following Mestrovic’s own example, let us not lose hope that, with care and concern, it might yet be restored to Eternity.

FIG VII View of the uncrated relief portraits at Our Lady of Mercy Cemetery, Doral, c. 1981. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

FIG VII View of the uncrated relief portraits at Our Lady of Mercy Cemetery, Doral, c. 1981. Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

Matthew Abess is the Visual Arts editor at The Miami Rail.