Marcelo Bonevardi: A Metaphysical Absence

Estrellita B. Brodsky

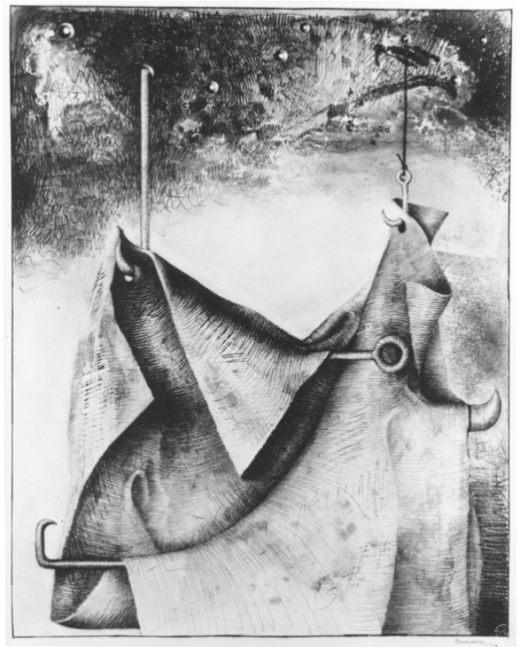

Marcelo Bonevardi, Skin, September 1974. Pastel and Charcoal on paper. 28 x 22 in (71 x 56 cm) Private Collection.

Marcelo Bonevardi, Skin, September 1974. Pastel and Charcoal on paper. 28 x 22 in (71 x 56 cm) Private Collection.

“Very cold, hard-edged abstraction never appealed to me. I did it for a short time when I was young but it never appealed to me. I always needed this kind of metaphysical, magical, mystical element.” — Marcelo Bonevardi, 1982

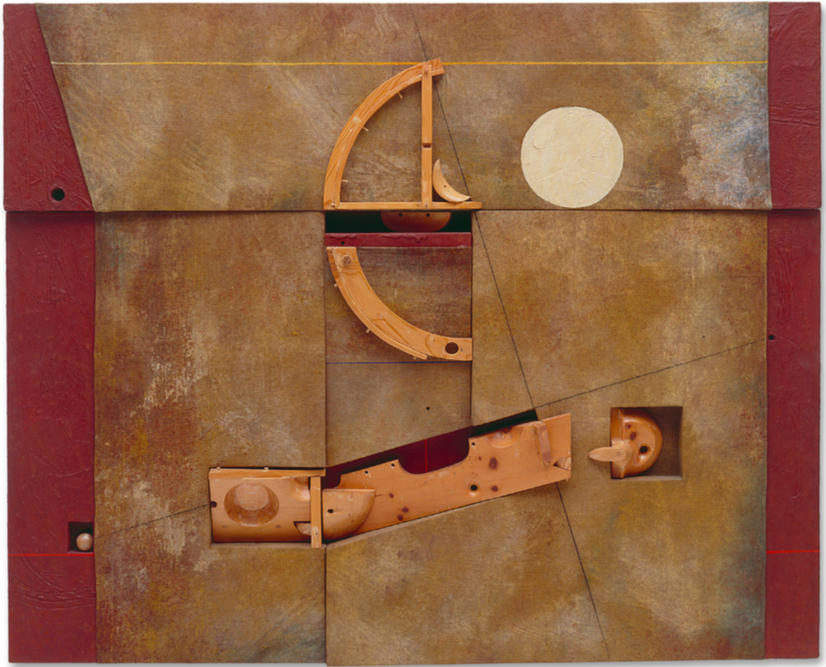

Marcelo Bonevardi, The Supreme Astrolabe, October 1973. Acrylic on stitched linen and wood construction with textured substrate, polished wood assemblage, and carvings. 70 1/4 x 87 inches. Courtesy the Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift: The Dorothy Beskind Foundation, 1973.

Marcelo Bonevardi, The Supreme Astrolabe, October 1973. Acrylic on stitched linen and wood construction with textured substrate, polished wood assemblage, and carvings. 70 1/4 x 87 inches. Courtesy the Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift: The Dorothy Beskind Foundation, 1973.

Marcelo Bonevardi’s aesthetic ideas are often related to the work of his fellow Argentinian countryman, the influential author, poet and visionary, Jorge Luis Borges. In the article “The Shadow Chaser,” Dore Ashton points out that Bonevardi shared with Borges a metaphysical desire to discover an aesthetic language.3 One might add that Bonevardi’s works also reflect a unique adaptation of concepts being explored by other artists and writers from Argentina and Uruguay. Most notably, from 1961 on, Bonevardi adopted the direct or indirect influence of these ideas to create an aesthetic vocabulary that included obscure, seemingly secret mythologies, replete with mystical and religious symbols, along with amulets, talismans, and astrological ciphers. These metaphysical references, housed within Bonevardi’s three-dimensional constructions, or represented in his haunting graphite and charcoal drawings, mark the artist’s self-proclaimed break with the course of modern art being advocated in New York journals and publications. Rather, Bonevardi proclaimed that he would follow his “own conclusions” and “passions” in seeking to transmit the “mysterious and magical.”

Bonevardi reacted against traditional painting and sculpture while adopting ideas of the universality of primitive and archaic occult myths. Of interest are his relationship to proposals by Borges, whose writings Bonevardi returned to that transformative year of 1961, as well as those of the Argentine artist and Borges’ collaborator Oscar Alejandro Schulz Solari, best known by his symbolic alias Xul Solar, as well as the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García and his School of the South. By no means does this approach suggest that Bonevardi was a “Latin American” artist whose work fits neatly into a regional mold. Rather, the premise is that the artist, after leaving Argentina and settling in New York City in 1958, reacted to a broad range of ideas, including, but not limited to, those of Argentine and Uruguayan artists and writers.

By the time Bonevardi left Argentina on a Guggenheim scholarship, the country had developed a flourishing avant-garde art scene. After World War I, Argentine and Uruguayan artists returning from extended stays in Europe laid a solid basis for experimentation. Borges and Solar were among the first generation of influential Argentines to return to Buenos Aires in 1924 with ideas absorbed from international art movements. Joining others who formed members of an avant-garde literary-artistic group named La Florida, which was identified with the publications Martin Fierro and Proa, Borges and Solar sought to develop a new form of non-European avant-garde. They elaborated the idea of incorporating the nation’s mythical folklore as an international Pan-American approach. A polyglot and avid student of the English occultist Aleister Crowley, Solar collaborated with Borges by illustrating many of his essays and books including El Tamaño de mi Esperanza and El Idioma de los Argentinos. Solar’s delicate, colorful watercolor illustrations incorporate his imaginary symbolic lexicon, astrological and occult signs, as well as symbols from Eastern religions and Mesoamerican culture to create a reinvented universal. The subject of a 2013 exhibition Xul Solar and Jorge Luis Borges: The Art of Friendship, Borges’ friendship with Solar and their shared intellectual concerns can be considered a mutual exploration.5 Their investigation into the possibilities of a metaphysical fantastic order that could incorporate both the local and global, the real and the imagined, the material and the absent, resonated with Bonevardi.

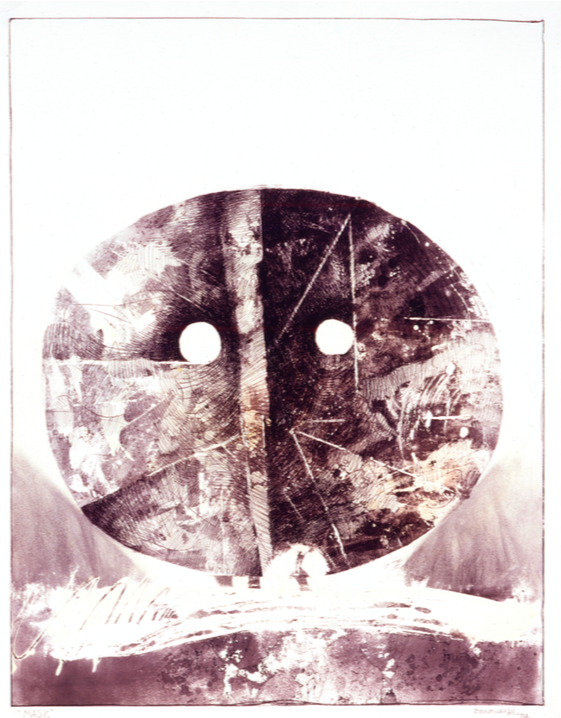

Marcelo Bonevardi, Mask, 1974. Watercolor and charcoal on paper. 27 1/2 x 21 1/2 inches. Private Collection.

Marcelo Bonevardi, Mask, 1974. Watercolor and charcoal on paper. 27 1/2 x 21 1/2 inches. Private Collection.

Throughout his career, in works such as Astrologer’s Table (1964), Astrologer’s Table II (1964), The Magic Project series (1963) and Amulet (1963) as well as a Chart for a Horoscope (1967), Bonevardi used multiple references to the occult and mystical experiences.6 Furthermore, although Bonevardi was never a student of the Uruguayan master, Joaquín Torres-García, his contact in 1961 with two of Torres-García’s School of the South students living in New York, gave him an opportunity to reflect on the Uruguayan master’s constructivist ideology that advocated pre-Columbian symbols as a universal aesthetic language. Julio Alpuy, a Uruguayan artist working in canvas and wood constructions, conveyed Torres-García’s concepts of embracing the pre-Columbian symbols as an alternative form of figuration. Particularly relevant to Bonevardi, as an Argentine living in New York, was the concept of a vernacular pictorial attitude situated in just such an idea of universalism.

Another student of Torres-García living in New York, the Uruguayan artist Gonzalo Fonseca soon became a close friend of Bonevardi. Fonseca incorporated Torres-García’s concept of art into his enigmatic work, creating fantastical architectural sculptures that blended pre-Columbian archeological sites into a seemingly contemporary world. By early in 1962, Bonevardi adopted a constructivist approach that incorporated the mystical proportions advocated not only by architects, but also Solar and Torres-García. More than solely a system for configuring the surface of a work or object, for Torres-García as discussed by Jacqueline Barnitz, “The grid and the symbols were [for Torres-García] all part of the same process, thus inseparable.”7 As Torres-García understood it, “real symbolism as the ancients understood it obeyed rules of rational structure without the need for interpretation or reading.” 8 This particular blend of primitivism presented within a modernist grid became a particularly compelling interest in Bonevardi’s search for a universal art form. Bonevardi’s exposure to Fonseca’s collection of pre-Columbian artifacts as well as his frequent visit to Mexico and its Mayan cultural heritage reinforced his curiosity about ancient cultures.

After 1961, Bonevardi began deploying three-dimensional architectural spaces that incorporate shadows and a wide range of materials such as canvas, wood, fabric and metal in a broad array of colors and textures. The construction Magic Project V (1962), demonstrates Bonevardi’s new process of building a wood structural support covered with stitched and painted canvas within which recesses or rooms expose hypnotic drawings of concentric circles. The different planes create shadows that blur the delineation between the object and its silhouette. The canvas serves multiple purposes as the support, the pictorial plane and a colored materiality. The differentiation between the real and the imagined, between craft and high art becomes indistinct. In other works, such as Oracle (1965), and Shelter (1965), Bonevardi creates similar structures with more elaborate cutouts in which wooden amulets and mystical ladders are encased. By late 1966, Bonevardi was painting directly on the textured substrate of the wooden structure rather than wrapping it in canvas as with Threshold Guardians (1966) and Trap for the Moon II (1966). Adopting titles that make religious or astrological references, these works no longer convey a pictorial space or a structural box but rather objects seemingly imbued with ritualistic powers that are closer in feeling to animistic African or pre-Columbian objects.

After frequent visits to Mexico in 1972, Bonevardi’s contact with indigenous American cultures reinforced ideas of a universal symbolism as proposed by Solar, Torres-García and also Juan Larrea. An influential figure living and teaching in Bonevardi’s hometown of Córdoba, Larrea was a Spanish poet living in exile in Latin America who had traveled in the 1930s to Peru. He later published treatises on the Incan culture he considered to be grand and mysterious including Corona Incaica in 1960, which Bonevardi admired and quoted. For Larrea, the Andean stone structures manifested a universal consciousness, and pre-Columbian culture offered Larrea near-mystical fascination as a model for a New Jerusalem in the New World.

While it is possible to understand Bonevardi’s work against this shared common ground, it is also critical to acknowledge its difference to the earlier masters’ works. An advocate of Solar’s legacy, Aldo Pellegrini, the Argentine critic and curator, wrote an introduction in 1969 for Bonevardi’s first Buenos Aires exhibition since his departure for the United States.10 Pellegrino characterized Bonevardi’s art as imbued with an impenetrable silence. His structures were to be considered not solely as contemplative sites, but also as abandoned archeological vestiges of mystical cultures similar to the way that shadows can suggest a ghostly human presence or mirrors present an intangible reversed image of an object. Bonevardi’s recollection of a storage cabinet in his father’s architectural office is particularly revealing. He remembered a box in which tools were kept. Each tool’s shape was outlined in grey in order to facilitate putting them back. As Bonevardi described it, even when the tools were missing or not correctly placed, each tool continued to have a presence in its shadow form.11 The silhouetted shape was as powerful as the tangible object it was meant to represent, if not more so.

Ultimately, it is this reflective approach that sets Bonevardi apart from his precursors who advocated for a universal language of mystical, religious, or pre-Columbian symbols. For Bonevardi, the universal signs and forms within his architectural structures can most often be interpreted as absent agents. In works entitled Annunciation (1980), Bonevardi reduces the Annunciation, often celebrated by the Renaissance master Fra Angelico with the angel Gabriel bearing multi-colored wings announcing the Incarnation to Mary under Roman arches, to a reflective hush. In Bonevardi’s related drawings and constructions on the subject of the Annunciation, the arches are denoted as a hollowed negative archway; the shaft of light is a solid wood plank he labels as the “Ominous Line;” the Virgin is an ovoid shape with two holes; and the figure of Gabriel with multi-colored striped wings is reduced to diagonal stripes of multi-colored stitched rough canvas. Bonevardi’s scenario is reduced to a short hand of a menacing premonition. In unpublished notes, Bonevardi records his interest in using “reflection” as an effect. And in work such as The Supreme Astrolabe (1973), a wooden sphere object has less materiality than its shadowed silhouette, which heralds its absence. Bonevardi’s project of making three-dimensional works that incorporate shadows as absent forms is unique. There is something quietly disturbing in the way the works whisper foretold warnings such as “the fall of the angel” or “the trapped angel,” or the “catholicity”.

The foreboding shapes in his constructions suggest silenced witnesses to another Argentine reality of which Bonevardi could not have been unaware and which cannot be ignored: the unspeakable frightening reality of Argentina’s “Dirty War.” The exquisitely drawn charcoal and pencil sketches as art historical references to the images of Piranesi’s Carceri series also serve to reinforce the conveyed sense of doom. Bonevardi’s drawings from the 1970s on seem to represent images of sadistic tools used by interrogators rather than those of a benevolent magician. It would have been impossible for Bonevardi to not be aware of the fact that Córdoba was the site of the 1969 civil uprising known as “El Cordobazo,” brutally suppressed by the military dictatorship of General Juan Carlos Onganía. The following decade witnessed increasingly brutal repression by the ruling military junta during the period from 1976 to 1983. In an effort to “purify society” by eradicating leftist dissidents, security forces were responsible for seizing and interrogating tens of thousands of people at detentions centers where fifteen to thirty thousand were eventually killed or disappeared. The largest detention center outside of Buenos Aires was located in a clandestine military base, La Perla-La Ribera, in Córdoba where Bonevardi was living at the time.

It is not surprising that Bonevardi would distance himself from the terrifying events suffered by Argentines during that time in what many call a nightmare. But the eerie photographs of abandoned or demolished buildings in his 1990s Demolition Series convey a more direct sense of loss, of lives gone missing, including those of friends Bonevardi knew directly who had been abducted by the security forces in Córdoba. The works are not a political statement, but rather a continuance of Bonevardi’s interest in a universal language. Whereas in his earlier explorations, the artist was fascinated by the universality of the mystical, astrological or pre-Columbian symbols, in these later works, images of modern day architectural ruins function as a form of contemporary archeology, one that forces us to re-inhabit a space of absence. The buildings’ cracked and damaged party walls, layered with broken painted plaster, represent a violent transformation. The edifice has been destroyed, its past purpose and previous tenants forgotten. We are, nevertheless, forced to face their absence. As with Cross (1994), in which the encrusted patina of plaster and paint leaves traces of an abandoned past, Bonevardi explores the metaphysical element of loss as a universal language for modern life.

Bonevardi’s uniqueness emerges from a transnational dialogue with artists he encountered either directly or indirectly in New York and Argentina. Among these influences are the ideas proposed by masters from the southern cone as well as the events happening around him in his home country. Often overlooked, these references quietly reveal themselves in Bonevardi’s compositions, in their constructions’ secret compartments and in his drawings of mysterious tools without purposes. Their meaning is never clear. Rather, Bonevardi presents the viewer with architectural spaces, tangible objects and their perceptible traces or absence. Ultimately, one is invited to confront these elements and enter at one’s own risk into an exceptional yet common world.

I would like to thank Gustavo Bonevardi and John Bennett for their generosity in making the Bonevardi archives available for research.

Estrellita B. Brodsky, PhD, is a New York-based curator, collector, philanthropist, and an advocate for the art from Latin America who has endowed curatorial positions in Latin American art at Tate Modern, MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is the founder of ANOTHER SPACE, a program established to broaden international awareness and appreciation of art from Latin America. Brodsky holds a doctorate in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University and has curated the first U.S. museum survey dedicated to Julio Le Parc at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM): Julio Le Parc: Form into Action, (2016-2017); the first U.S. retrospective of the venezuelan kinetic artist Carlos Cruz-Diez at the Americas Society in 2008; and the exhibition Jesus Soto: Paris and Beyond, 1950-1970 at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery in 2012.

An exhibition of major works by Marcelo Bonevardi will be on view at Courthouse One in Miami’s design district from December 2nd through the 10th from 11am till 6pm, and from December 11th through 31st by appointment.