Ryan Sullivan

Erin Thurlow

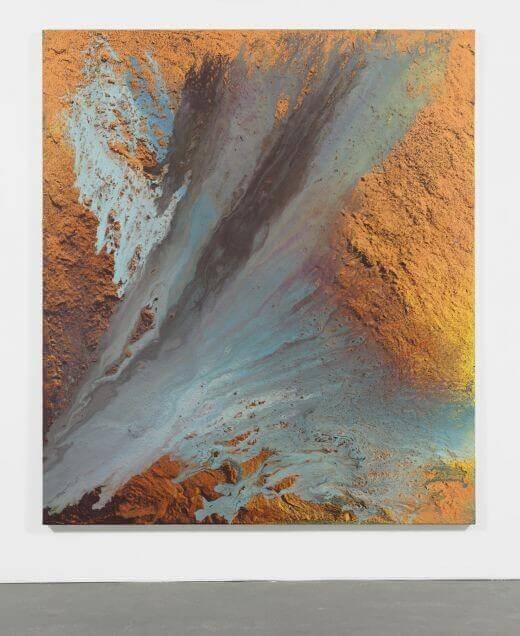

Ryan Sullivan, Untitled, 2014. Latex, synthetic polymer paint, enamel, and lacquer on canvas, 243 x 213.4 cm

April 16–August 9, 2015

Minutes—or maybe even seconds—into viewing Ryan Sullivan’s paintings at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, the work induced a kind of reflexive mental search algorithm, bringing to mind a succession of names, images, and ideas: Jackson Pollock, Gutai, Robert Smithson, Andrei Tarkovsky, Star Trek, Edward Burtynsky, Paul Virilio, NASA, and global weather imaging. Although abstract, the paintings are recognizable in a way that makes metaphor and analogy feel unnecessarily belabored. Sullivan seems to understand this, as the works are all untitled.

The large-scale, identically formatted paintings feel contemporary, even as the methods for creating them could seem outdated, not only by the half-century since the flagging of Abstract Expressionism, but also by imagined aeons. The process looks geologic. Sullivan’s technique appears to be a confident combination of accident and skill, pouring paint that pools and dries unevenly to make surfaces crackle, bulge, and fissure, topographies caused by the tectonics of possibly incompatible materials. These surfaces are splashed and sprayed with more paint, often at acute angles that accentuate the canvases’ irregularities in a way that reads as uncannily as light (or wind or other atmospheric phenomena) raking a battered landscape, as photographed by a high-flying drone, or a satellite.

Sullivan allows the materials to interact according to their own properties, performing much of the work across the vast picture plane, creating a huge amount of detail, giving the paintings the feeling of large, high-definition screens. Of course, there is a danger for the artist in hiding his hand and allowing so much of the process to be left to the inherent behavior of the materials. While getting lost in swirling pools of color can be a nice aesthetic experience, like staring into a fire or spotting shapes in passing clouds, it can also be boring. But Sullivan mostly saves his paintings, and viewers, from that fate. When the imagery begins to meander, he manages to keep the paintings moody and contemplative, succeeding by turning up the contrasts and keeping the action palpable.

Sullivan’s wide palette can call to mind lava, desert, aquatic expanse, superstorms, or cosmic rays, and the paintings often imply planetary surfaces wracked by natural phenomena or natural landscapes wrecked by the kind of industry that manufactures the very pigments and chemicals that were used to make them. But this kind of allusion barely warrants mentioning. It was all there as soon as I looked. These are not paintings in search of a critic, accessible as they are to the viewer in a way that can be difficult to pull off.

The illusion of light in the paintings, and their subsequent resemblance to photographs, created by the artist splashing or spraying paint across the very real bumps and ridges, has the unsettling parallel effect of describing optical phenomena while simultaneously physically embodying it. Photographs do this, too, but in a way that coaxes us to forget the medium and actually obscures their identity as objects. In a jarring contrast, these paintings resemble photography while retaining their own highly tactile, solid aspects.

The most evocative of Sullivan’s paintings act almost too rapidly on the senses, and the brain is forced into its familiar game of pattern recognition. Rather than a singular image, what is actually being evoked is the blazing speed of the Internet itself. These are not ideas/images that we process with any real reflection, at least not immediately. They wash over our minds like a stream, the way we experience most information in our overstimulated existence. But this happens in a way that does not leave us without agency. As much as Sullivan’s painting is inspiring these image readings, they remain abstract and the brain works, pleasurably, to complete the picture, and to recall and even generate ideas, if only fleetingly. Considering how cerebral the works feel, it is doubly paradoxical that Sullivan produces them in such a highly physical way, vicariously grounding us and reminding us to return to our own visceral, desiring, aging bodies.

I initially thought that the paintings were successful in part because these qualities would translate well to the computer screen, where many of us actually view art today. However, looking back at the images on my laptop for reference, I was disappointed. The unexpected correlation between the abstract and photographic quality is still viable, but the works lose much of their tension once flattened to the virtual and forced to forgo the physicality from which they draw their internal contradictions. It turns out that while visual prosthesis and digital information processing must be fixed firmly in our minds for these paintings to perform in the way I describe, those media are actually poor portals for experiencing them.

Of course this endeavor of situating and justifying the act of painting in the face of increasingly powerful imaging technology has been the engine of modern painting, one of its central premises as well as its source of peculiar anachronism and ascribed value, at least since the invention of the camera. By locating the sensual connection between the body and the image, Sullivan’s paintings tilt at the limits of the sensible as delineated by our virtual immersion in a world of images. One must be in the presence of this art, and be present in one’s body, in order to fully grasp it.