Living, Together: Architectural Cohabitation

Terence Riley

Share House in Nagoya, Japan

Last month, the New York Times published both a news article and an op-ed piece on the topic. In the news article, the writer provided statistics describing the disillusionment that the Millennial Generation and Gen-Xers and were demonstrating towards suburban living.Since 2000, the regions surrounding New York City “have experienced a drop in the number of 25- to 44-year-olds, with the declines particularly sharp in more affluent communities.” As an example he cites one well-to-do community that recently counted a 63-percent decrease in Millennials and a 16-percent decrease in Gen-Xers.1

The reporter cited two interpretations for the demographic decline, which he stated was not only happening in New York’s suburbs but also those surrounding Washington, D.C.; Chicago, and Boston. The first is the theory that younger people are more attuned to the cultural and social diversity of urban life and less enchanted with the demographic homogeneity in the suburbs. The other interpretation is economic. The suburbs are also increasingly expensive and, particularly in wealthy communities, there is a serious lack of affordable housing for young families.

Vishaan Chakrabarti elaborated on this phenomenon in his op-ed piece “America’s Urban Future,” published by the Times the same day. He writes, “The influx of young people into cities is the biggest part of the story, and rightly so. The ranks of the so-called Echo Boom—the children of the baby boomers—constitute about 25 percent of the population. After nearly 100 years in which suburban growth outpaced urban, Millennials are reversing the trend. Once only a fraction of young college graduates wanted to move to cities; now about two-thirds do.”2

Some Millennials, however, are moving back to the suburbs—to live with their parents. According to the Wall Street Journal, “In a report on the status of families, the Census Bureau on Tuesday said 13.6% of Americans ages 25 to 34 were living with their parents in 2012, up slightly from 13.4% in 2011.”3 For various reasons, living on their own has become too expensive for many young adults, a sad fact of the state of the economy during their early working lives.

Urban living is certainly not cheap, although high rents are still more affordable than down payments on suburban homes. In most cities, mass transportation is far more affordable than the annual costs of owning a car. Perhaps more importantly for Gen-Xers and Millennials, the city is where the jobs are. And since most of this cohort will change jobs many more times than their parents, the kind of networking that is inherent in urban life is essential to their professional careers.

In this sense, not only do young people need cities but cities also need young people. Or, in the words of New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, “Developing housing that meets the needs of how New Yorkers live today is critical to the City’s future economic success.”4 According to the department’s analysis, the city has one million studios and one-bedrooms, far fewer than the 1.8 million households that consist of one or two persons. Moreover, many of those smaller apartments are substandard and developers are not incentivized to create more.

To address this need, last year Mayor Michael Bloomberg initiated a design competition for “micro-apartments” on city-owned land on East 27th Street in Manhattan. Teams of developers and architects were invited to participate. The zoning code’s requirement of a minimum 400 square feet per unit was waived. The winning scheme, with 55 new micro-apartments measuring between 250 and 370 square feet, was submitted by nARCHITECTS (Eric Bunge and Mimi Hoang, principals), Monadnock Development, LLC and the Actors Fund Housing Development Corporation.

Each unit in the winning design comprises two distinct zones: the kitchen, bathroom, and storage area in the rear and, in the front, a well-proportioned flexible area serving as the primary living and sleeping area. (Ill. 1) (Yet another generation of newcomers to Manhattan will be discovering the joys of the Murphy bed, which folds up into a closet during the day). Floor-to-ceiling heights just under ten feet provide a bit of breathing room (and overhead storage), as do the Juliet balconies that open the unit to the light and air.

Ill. 1 nARCHITECT’s ground floor. Copyright Ledaean.

ill. 2 A cross section of nARCHITECT’s micro apartment. Copyright MIR.

As far as the last, my vote would be for Wynwood. For one thing, the people most likely to embrace the micro-housing/shared space concept are already there—during the daytime at least. They can be found in places like Panther Coffee, laptops open, cell phones in hand. Or, places like The LAB, founded by Wifredo Fernandez and Daniel Lafuente to, in their words, “drive and support the growth of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Miami.”6 Located in a converted 10,000 square foot warehouse, the open character of The LAB lends itself to formal and informal collaborations, networking, and group events. Housing that reflected the same attitude would go a long way toward making Wynwood a stable neighborhood with a 24-hour residential character.

The micro-apartment/shared-space concept inserts another rung on the economic ladder that reflects the needs of the Millennial generation. Even so, other examples exist of even lower economic thresholds for addressing the cost of housing. Consider Share House, designed by Naruse Inokuma Architects (Jun Inokuma and Yuri Naruse) and built in Nagoya, Japan. Share House is defined as “a model of a residence in which multiple unrelated people live and share a kitchen, bathroom, and living room. In Japan, demands for share houses are increasing, mainly for singles in their 20s and 30s.”7

Share House has 13 identical bedrooms, each around 8’ x 10’, dispersed along the edges of an otherwise open flowing three-story structure. Spaces for meals and socializing are shared in a loose, informal way. Rather than a single dining table, occupants can choose where to sit—at tables of different sizes or on stools at the kitchen counter. Rather than a single living room, there are a variety of shared spaces, some larger, some smaller, some more central, others less so. (ill. 3)

Ill. 3 Share House

The flowing interconnected spaces of the Share House give it a generous open feeling, belying its incredibly frugal use of resources. The 3,500 square feet of the Share House is the same size as a so-called McMansion. However, the latter rarely provides shelter for more than a family of five, while thirteen individuals occupy the Share House. Both in terms of the of initial usage of physical resources per capita and the ongoing energy usage per capita, the Share House represents an incredibly green way of living.

Should Miami consider such an experiment in communal, environmentally sustainable living? You probably would not believe how many laws and regulations would have to be changed to allow it. For starters, the current zoning code does allow “dormitories,” but they have to be associated with an educational institution or place of employment. The code also allows “community residences,” but only for children, the elderly, the physically or developmentally handicapped, and the non-dangerous mentally ill. The code would also require the project to have 13 off-street parking spaces, even as the City tries to convince people to use mass transit. The required area for parking would occupy, by code, as much space as the house itself.

So, what about the Gen-Xers with kids that need a two- or three-bedroom residence and have decided to stay in the city rather than decamp to the suburbs? In Miami, the rapid increase in condominium apartments in the last decades has inexorably reduced the number of single-family houses available and made those that still exist more expensive. Being priced out and opted out of their parents’ dream of building their own home in the suburbs, is their only choice to shop around for the endlessly repetitive apartment plans offered on the commercial real estate market?

The answer is provided in a book titled Self-Made City, edited and authored by Kristien Ring,8 which is a case study of 125 co-operative apartments houses—referred to as “co-housing”—built in Berlin between 2004 and 2012. The critical distinction here is that co-housing is developed by the people that intend to live there, rather than real estate companies.

A project called Ten-in-One serves as a good example of how co-housing is created. In 2002, Christoph Roedig and Uli Schop—a gay couple who are also partners in an architecture firm—were both in their 30s and hoping to have a place to live in the city of their own design. They identified a site in Berlin’s Mitte neighborhood, which still had open areas where buildings had been bombed during WWII and where the Berlin Wall had been built and subsequently demolished.9

Ill. 4. Ten-in-One’s rooftop apartment. Photo: Andrea Kroth

In addition, the group collectively decided on communal amenities. 2800 square feet of the site was reserved for green space, including a communal garden. Since the top floor was coveted by most, it was judiciously decided that it would be available to everyone. A rooftop deck offers a sweeping view of the city. In addition, a studio apartment on the roof is used for frequent community dinners and can be reserved when house members have overnight guests. (ill. 4)

In the end, the members of the Ten-in-One project paid less for their apartments than did the average buyer in the city. One reason the costs were below average is the fact that there is no profit being generated from the process. The residents are only paying for the actual costs of the project. Moreover, they all got a custom-designed apartment and the architectural quality is far above the average. Also, a larger investment in better materials insures lower maintenance long term.

There is no reason to think that the relatively small-scale co-housing concept wouldn’t work in Miami, especially for those who have already saved enough to be thinking of a down payment on a condo. Does the city have an interest in promoting the concept, even creating incentives to make the concept more widely accessible? The Miami entrepreneur and activist Andrew Frey would argue in the affirmative: “Small buildings can help a regional plan achieve its goals. Small buildings add up to urban neighborhoods that are dense and mixed-use, which support walking, biking, car sharing, and mass transit. These neighborhoods promote public health and use water and sewer infrastructure more efficiently. Neighborhoods made of many small buildings (as opposed to a few big ones) help spread the wealth created by revitalization.”11 In other words, if the city wants to see urban neighborhoods develop in a more coherent and sustainable way, making it easier for co-housing groups to achieve their goals would be a good way to do it. This could be achieved by making the acquisition of city-owned land less onerous, by offering incentives to people willing to build in areas that developers often ignore, and by allowing greater density when that is a key factor in a project’s viability.

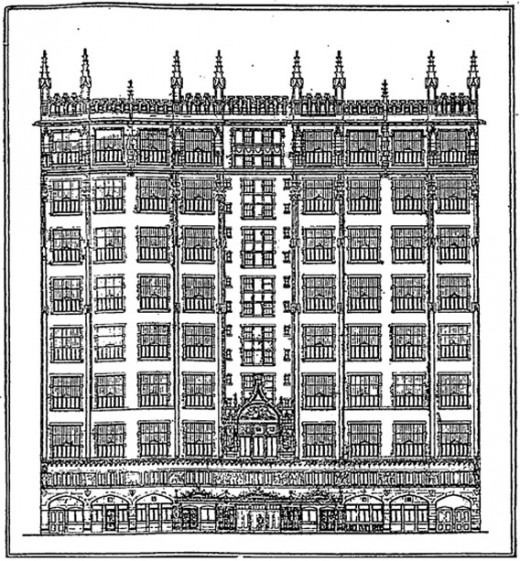

The well-to-do and the wealthy could benefit from the co-housing concept as well. In a number of cases they, in fact, already have. One of the best examples is the Hotel des Artistes apartment building in New York City, which was under construction 100 years ago. (ill. 5) The purpose of the project was to create a building where artists could live and work with neighbors who were also artists or otherwise involved in the cultural life of the city. Penrhyn Stanlaws, a successful commercial artist, created what was called a “syndicate” of like-minded people to develop the property at 1 West 67th Street. They hired the architect George Mort Pollard to design the building, an 18-story, neo-gothic structure with 72 apartments.12

Ill. 5. Hotel Des Artistes Elevation

In what today would be considered a virtuous if not noble act, the members of the syndicate also decided to develop the lower floors as small, rental apartments for artists who needed affordable space for living and work. These, too, were duplexes with the same provision for double height spaces. (ill. 6)

A double-height studio apartment in the Hotel des Artistes.

It’s hard to imagine the 1% choosing co-housing today, even the upscale Hotel des Artistes variety. I think they’re going to miss out on the fun. The 99%, meanwhile, may just be able to find housing that reflects their way of life, offers a more sociable alternative to traditional urban housing, and creates neighborhoods that are culturally and architecturally vital.

1. Generation X comprises those born between the mid-’60s and the mid-’80s. The term was coined by Robert Capa, and popularized by Douglas Coupland. The Millennial Generation follows.

2. “America’s Urban Future”, By Vishaan Chakrabarti APRIL 16, 2014 NYT

3. More Young Adults Live With Parents By Neil Shah Aug. 27, 2013 11:21 p.m. ET WSJ

4. Mayor Bloomberg Announces Winner of adAPT NYC Competition to Develop Innovative Micro-Unit Apartment Housing Model

http://www.nyc.gov/html/hpd/html/pr2013/pr-01-22-13.shtml

5. Micro Digs’ Sliding TV, Murphy Bed Tempt Singles: Review By James S. Russell Jan 29, 2013 12:26 PM ET Bloomberg News

6. http://thelabmiami.com/about-us/

7. http://www.dezeen.com/2013/08/29/share-house-by-naruse-inokuma-architects/

8. ‘Self-Made City. Berlin: Self-Initiated Urban Living and Architectural Interventions’ by Kristien Ring, edited together with the Senate for Urban Development and the Environment of Berlin, JoivisVerlag Publishers, 2013.

9. In addition to the information available in Self-Made City, the project was profiled in the New York Times. A Showpiece of Communal Living in Berlin, by Sarah Wildman, November 9, 2011. The architects provided additional information.

10. The ten formed a legal corporation to enable them to develop the project. When complete, the building became a condominium, with each of the owners having title to their apartment. For more details, see Self-Made City, op. cit.

12. Streetscapes/Hotel des Artistes, 1 West 67th Street; Cornerstone Building on a Block of Artists’ Studios. Christopher Gray, NYT, May 14, 2000. Over the years, newer tenants renovated their units, adding kitchens. The lower floor units are no longer rental spaces, having been sold to individual owners. The building still has an aura of upscale bohemianism, but the last artist to live in the building was LeRoy Nieman, who died in 2012.