Miami: A Driving Tour

Paddy Johnson

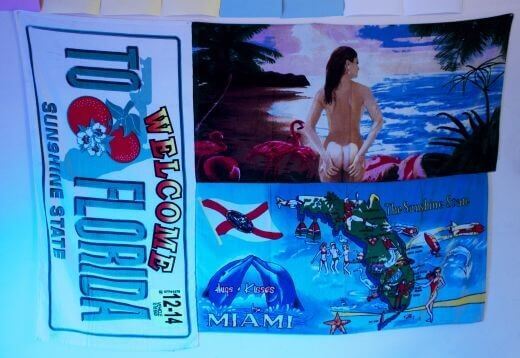

German Caceres, Emma Del Rey, Ani Gonzalez, Dianna Grace, Michelle Izquierdo, Genevieve Lacroix, and Joshua Veasey, The Miami Room, 2015. Installation views: ARTSEEN, Miami, February 2015

“Don’t walk. Drive.” I can’t count the number of times I was given these instructions while visiting Miami, regardless of how close I was to my destination. I was offered this advice after having parked just a two-blocks’ walk away from Pérez Art Museum Miami to see a pop-up art project nearby.

Perhaps more than anything else, driving my rental car around the city defined my three-day stay in Miami. This marks a significant departure from my typical visit. Like most art tourists and professionals, I head to Miami Beach in December for the fairs, and if I travel around the city, it’s in a cab or art fair shuttle bus. I don’t rent a car, I don’t expect to get around quickly, and I don’t anticipate spending much time on Biscayne Boulevard. During those trips, I spend most of my days studying the floor plans of fairs and my nights blogging from a perch on my hotel bed.

For this trip, I resolved to learn more about Miami culture and how it shapes the local art scene. Does the city’s car culture affect the art being made in any way, I wondered? What about gentrification?

Celebrity culture? In response, a few observations on the scene from a regular fair visitor, art expert, and Miami newb.

BISCAYNE BOULEVARD

It’s hard to exaggerate the importance, for any tourist, of a road that runs in a straight line. Nearly all my scheduled stops were off Biscayne Boulevard, making it nearly impossible to get lost. I stayed at the New Yorker Boutique Hotel, one of the many motels on Biscayne marked by their Bauhaus-inspired modernist design and kitschy 1950s-style neon signs. (Some are designated historic buildings and many are under repair.) Hallmark Miami baby-blue paint lined the white steps up to my room. The color

almost perfectly matched the sky.

These hotels were once designed to lure middle-class travelers, but eventually became infested with drug dealers and hookers. They have that look, too. My room offered no dresser and a shower that only occasionally drained. None of that seemed to matter each morning, though, when I stepped outside, the

bright sun glowing on my back. There may be no better reprise from New York winter than palm trees and a pool of warm air.

WYNWOOD

Hipsters ruin everything. Apparently, the Wynwood district is now defined by its robust nightlife scene and the galleries are being pushed out. Few cities can escape gentrification, which is largely driven by city policy and the buying patterns of the wealthy. Surely, though, the resources spent on commissioning graffiti have affected those patterns, as they’ve done a better job of branding the neighborhood as a center for bars than as a gallery district.

David Castillo Gallery left Wynwood last year, and the bulk of the remaining galleries resemble those that cater to tourists in New Orleans. Mostly we’re talking bold, graphic poster-like paintings, worship of the distorted figure, and black-and-white celebrity photography. One of the outliers

worth noting: Charley Friedman at Gallery Diet. Friedman’s show was defined by a spinning metal apparatus that supports a cloud of colorful beach balls, a wall-size yellow drawing comprising only densely arranged horizontal lines with a figure looking on, and a room full of pencil drawings vaguely related to both. Having seen the artist’s drawings and sculptures of figures spraying colored rain from their hands, this show was mostly impressive for its demonstration of the artist’s growth. Every time a figure gets introduced to this work, fantastical, cheese-ball narratives ensue. Better to just leave all that out and let viewers create a narrative on their own, as Friedman has mostly done here.

German Caceres, Emma Del Rey, Ani Gonzalez, Dianna Grace, Michelle Izquierdo, Genevieve Lacroix, and Joshua Veasey, The Miami Room, 2015. Installation views: ARTSEEN, Miami, February 2015

DOWNTOWN

Downtown Miami reminds me a little bit of my neighborhood in Queens. Much like home, Miami’s downtown is filled with faltering mall arcades and renovated bank interiors. Buildings barely stretch into the sky.

This was probably my favorite part of the city (despite the parking costs). Largely populated by small businesses run by immigrants, hoteliers, and at least one crumbling department store, more character and diversity exists here than in most places I visited. A few standouts: In the jewelry district, a diamond-encrusted soccer ball surrounded by tiny necklaces. In the New World School of the Arts ARTSEEN exhibition space, a makeshift art lounge installed by students included a wall mural made of Miami

towels, a hanging umbrella lamp shade, and a collection of Miami postcards that were probably printed in the ‘90s. La Epoca, the iconic Cuban department store located in a former Walgreens houses an installation of hanging white balls from its ceiling. Everything was on sale, so it seemed like a good time to shop, as well.

DE LA CRUZ COLLECTION

I can’t say I was overwhelmed by the de la Cruz Collection, which currently has a checklist of predominantly male blue-chip artists on view: Dan Colen, Rashid Johnson, Sterling Ruby, Rudolf Stingel, and so on. It’s a bit of a disappointment, because within the city of Miami, I’m told the family is famous for its generosity and educational programs. (And of course, they did host my talk, so I’m grateful for that.)

That talk took place in a room filled with Rob Pruitt’s rainbow gradient happy faces and Félix González-Torres’s candy piles. Pruitt’s faces supposedly relate to his childhood desire to paint happy faces on famous Expressionist works, whereas the piles of candy represent Gonzáles-Torres’s late father’s weight— viewers are invited to take the candy, diminishing the pile as death did him. Basically, the works have nothing to do with each other beyond their formal similarities, so the overall effect of the pairing is only to diminish the metaphoric possibilities of the candies. Bummer.

Undoubtedly, Ana Mendieta’s coffin photos spoke most powerfully. In them, she placed herself or an outline of herself inside a number of different coffins—a burning coffin in the shape of her figure, a chalk outline of her figure on stone, her figure laying among overgrown weeds. Knowing she either jumped or was pushed to her death in 1985 makes those works seem prescient.

PÉREZ ART MUSEUM MIAMI

Man, even the parking at this new $131-million museum is fancy. Instead of painted lines on asphalt, drivers park on gravel with thin flat cement lines dividing the spaces. Classy.

As for the art, Global Positioning Systems currently fills a good portion of the museum, a collection show paired with some private loans. Basically, it’s a hodgepodge of contemporary art organized loosely into categories the curators were tasked with conceiving: History Painting, Forms of Commemoration, Visual Memory, The Contested Present, The Uses of History, and Urban Imaginaries. Thus, the show isn’t about reflection or historicizing so much as it is about figuring out how to work with the collection and the new space.

We see a few canonical standards, but not many—Christian Marclay’s collage of people in movies answering the phone, a small Hernan Bas painting, and a John Baldessari constellation of cropped and framed movie photographs in which he covers faces. We see plenty of middling work, though the worst is Thomas Hirschhorn’s oversize CNN necklace in gold. It’s fashioned in the style of hip-hop jewelry to suggest that news is just another form of entertainment, a message so simplistic and obvious, we’d learn more simply by subjecting ourselves to the network itself.

But there are highlights, too. Of all the works on view, I was probably most pleased to see Paul Chan’s Untitled (After Robert Lynn Green, Sr.) (2007), a photo of a New Orleans resident holding a sign with the first lines in Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot. The sign reads “A Country Road / A Tree / Evening.” According to Chan, within Godot exists a “terrible symmetry between the reality of New Orleans post-Katrina and the essence of this play, which expresses in stark eloquence the cruel and funny things people do while they wait: for help, for food, for tomorrow.” In engaging New Orleans residents to reenact the play, Chan meant to encourage people to think critically about what value means.

At that time, through to today, those lessons remain valuable.

Paddy Johnson is the Miami Rail’s Spring 2015 Visiting Writer. The Visiting Writer Program is generously supported by the John S. and the James L. Knight Foundation.