- BEST SHOW: CATHERINE INCE ON ARCADES PROJECT: CONTEMPORARY ART AND WALTER BENJAMIN AT THE JEWISH MUSEUM, NEW YORK, 2017

- WILLIAM WALKER: BETWEEN HIS ARRIVAL & EXECUTION IN HONDURAS (1860)

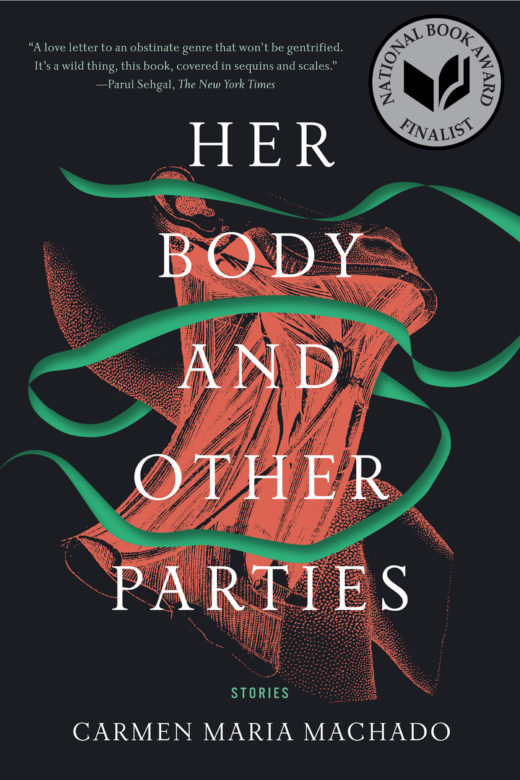

How the Voice Outlives the Body: A Conversation with Carmen Maria Machado

Lynne Barrett

Of course, overnight acclaim is not really sudden. Before this moment came years of work. Machado’s stories, appearing in such magazines as Lightspeed, Strange Horizons, Guernica, Gulf Coast, Granta, and Tin House, had blown readers away. Many were selected for award anthologies including Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy, Best Horror of the Year, and Best Women’s Erotica. Her fiction draws upon the traditions of horror, fantasy, and the fairy tale, but at the same time reflects pop culture and our moment’s most pressing questions. She writes about sensuality, pain, betrayal, the grotesque, and the beautiful, focusing, as her book’s title suggests, on women’s bodies as centers of experience. She does this with a boldness and freshness that makes the reader feel these stories have never before been told.

Machado is now writer-in-residence at the University of Pennsylvania and lives in Philadelphia with her wife. On the Saturday morning of the Book Fair, while announcements and music competed outside, and crowds extended for blocks in every direction, celebrating reading, writing, books, and community, we found a quiet nook in the stacks of the Miami Dade Wolfson Campus library.

Lynne Barrett: I want to ask you first about the short story form. You’ve done so much to stretch and bend and play with it and put other forms into it. Why has the short story attracted you and why does it work so well for you?

Carmen Maria Machado: I love reading short stories. I’m one of those writers who, if you recommend an author to me and I go to a library or a bookstore and I see a novel and a collection, I’ll always pick the collection first. I feel the collection is a way of taking the temperature of an author’s skill and you can see a range. And I love novels, too, but I also find novels kind of baffling. I feel like a novel is like a car. I don’t know how it works; I don’t know how it goes together. I can get through it, but I don’t really know how to do that—

LB: I share that with you. I’ll start something I think is a novel—

CMM: And then it becomes a short story.

LB: Yes, you’re writing and, suddenly, there’s the end.

CMM: I just did this last month. I had something I thought was going to be a novel, and I came to the end of it and there were twenty-seven pages, and I thought, Well, great.

LB: I think that’s in the nature of wanting to tell something with a shape to it. It’s a baggier thing, a novel, in some ways. But I was also thinking about how much your stories come from a tradition of the tale, fairy tales, myths, that in themselves have this idea that life can go from here to there fairly fast. You can feel the world turning upside down, quickly, so there’s more vertigo to the short story.

CMM: I think it was Ray Bradbury who recommended you start and finish a short story in the same day, which is an insane piece of advice, but is really interesting. I think the idea being that you can capture a mood or something if you can finish it one sitting.

LB: A grasp.

CMM: Yes, You can wrangle that essence, which is impossible with a novel. It’s like a house versus a small beautiful object. I’m obsessed with the glass paperweight version of it. I’m interested in the house, the novel, but it’s just not something I know how to do right now. I keep trying. Maybe one day I’ll learn, or I’ll trick myself into writing a novel, which is my plan. I have a novel in stories I’m working on right now so maybe that will be the key, the way in. But I just love the form, and I think I’m a natural short story writer. I feel I’m able to get a handle on the form in a way that feels very instinctual to me.

LB: Something else that I’ve seen is that there’s been a change in what magazines will carry. There used to be a certain notion of what the short story was because of the minimalists, but there’s been an opening up. I think that’s partly because magazines don’t have to deal with certain marketplace elements. For instance, you can have something that makes you more uneasy, because it’s merging genres, where for the novel they want to shelve it somewhere in the bookstore in a particular category.

CMM: Mmmm, I mean, I think—

LB: Feel free to disagree—

CMM: I just think that there are certain things you can do at a short story length that’s impossible to do at a novel length. I’m thinking about, for example, my story “Inventory,” where that is a perfect sort of constraint for a short story, but try to imagine that at novel length. I mean it’s possible, I’m sure some writers could do it, but for me it just feels like that works better as a short story.

LB: Yes, because it’s got that force of a list or catalog, while telling an apocalyptic tale. I think this is true for a number of your stories, because they operate on a progression that gets to, or in this case right up against, its end point. And “Inventory” builds layers of progression. There’s a personal catalog of “Every person I have ever loved. Every person who has ever loved me.” But also we follow the geographical movement, west to east, fleeing the advance of an epidemic, so that we are wondering whether anyone will still be left alive. Which gives a personal story the excitement of an adventure story. But if stretched over a novel, it would lose the tension of that speed.

CMM: I think the novel has a lot of formal space. I just don’t know how to access it. I don’t want to talk shit on the novel. It’s an incredible form. For me, and everything I try to do, I feel the short story is the way in for me. At least right now.

LB: And you’ve been able to do amazing things with it so there’s nothing wrong with that.

CMM: No, not at all.

LB: Except that there are people who want novels out of you.

CMM: You know it’s hard. And it really makes me sad, because for a lot of prizes it has to be a novel; it can’t be a short story collection. This book isn’t eligible for the Booker Prize or whatever, because it’s not a novel.

LB: Shame on them.

CMM: (Laughs) Not that it was going to win the Booker Prize. But, do you know what I mean, there’s an implication that there’s a certain sort of serious literature and that with the short story form you’re a dilettante, you’re just jetting about. But we know from Alice Munro, the Nobel Prize—

LB: Yes, that’s a great example. It turns out if you persist long enough and your work accumulates enough force, then people see it. I also think that we have a lot of short forms in our entertainment, some of which substituted for the short story. This semester I’m teaching a class in mystery and suspense, and one of the books is Sarah Weinman’s anthology Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Women’s Domestic Suspense.

CMM: I also taught that book, which is so great.

LB: And they love it, but they often haven’t heard of more than one or two of the authors. And you see there was a whole world of the short story as a moneymaking proposition for women in commercial magazines from the ’30s through the ’60s. And now, because of the Internet, it’s easier to invent a magazine. It seems as if every day I’m seeing something new as they keep redefining mixtures of genres, open to fresh subject matter, experimentally trying to figure out how to capture stories they want to see.

CMM: In the genre world the short story is taken a little more seriously as a form. Not coincidentally, this was the world of pulps, science fiction and fantasy. People like Ray Bradbury supported his family writing short stories and selling them to magazines. In the genre world there are professional rate standards for authors.

LB: Very clear ones. You can see they know they’re going to be assessed based on that.

CMM: And you can get things like Nebulas, Hugos, Shirley Jackson Awards. All those awards have short story categories, so you don’t need to have published a book. They can say you wrote a really excellent short story that was published in a magazine this year and we want to honor that.

LB: This leads me to a question I had, because you’ve also moved around a lot in terms of the magazines in which your work has been published. It must be that you can look at something you’ve written and say this can go in a number of directions. Would you say that you’ve been shifting or experimenting with where you send things?

CMM: It depends on what the story is. Sometimes people have requested work from me, so if it’s a magazine that I want to be published in, I have those in a list, and when I have a new story I’m thinking, Who’s a good fit, okay this person asked for work from me, I’ll try it. So that’s part of it.

It also depends on the story itself. I’ve published some stories in literary magazines where I’ve been told by a genre magazine that the fantastic element is too slight, they think, to satisfy their readers. Which is perfectly fine; they know their readers. Or I really want the story online. Or I haven’t published in this magazine yet, and I really want to. I’ve been working on this book and I have other books I’m working on, so it used to be that I was constantly submitting and I’ve slowed down in the past couple of years, but I do my best to go back and forth. I have a soft place in my heart for the really excellent genre magazines, with all their free content, that professionally pay their writers and are just on it in so many ways and are really culturally important.

LB: Which is interesting because a lot of that comes from the fact that they do have readers.

CMM: Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

LB: As opposed to the fact that there are magazines that are bringing in money from the writers in some cases, which is a different model.

CMM: Exactly. These [genre] magazines may have subscription models, some of them do fundraising, some do anthologies, there are all these ways they raise money, but they’re always clear: We’re paying our writers, this is our rate. There’s no weirdness about it, which I think is beautiful and really encouraging, and I wish certain literary magazines would adopt that same set of principles.

LB: You’ve published in Granta, and I have here this past summer’s Tin House that has your first post-collection story “Blur” in it. One thing you can see is that top literary magazines like these also want to make sure they’re reaching readers. And the breadth of what’s being published seems to have widened, somewhat.

CMM: Yes, though I think Tin House has always been in its own universe.

LB: Yes. I see them as committed to story, as opposed to some magazines that I think are committed to a certain kind of restraint. Storytelling that values boldness must have control but not necessarily restraint, if I can put it that way. Another place where you’ve been publishing stories is in anthologies, which can allow exploration of all sorts of subjects and forms.

CMM: I get a lot of anthology requests, and at this point I’m not doing many of them, because I’m just too busy. But I must say it has given me some opportunities to write stories that I had percolating but had not had an excuse to write.

LB: So it operated as a prompt in a way?

CMM: In this collection, “Eight Bites” ended up not being in the anthology because I had to withdraw it because it had gotten away from the prompt, but initially it was commissioned by an anthology that came out last year called The Starlit Wood, an anthology of retold fairy tales, a beautiful book. And so I had claimed “The Little Mermaid,” and, if you look, that story does have some very faint Little Mermaid in it.

LB: There we are at the seacoast—

CMM: And it has the Pomeranians Flotsam and Jetsam, and the doctor who is Ursula the Sea Witch.

LB: And the sisters. I wrote down this passage from it where she’s speaking to her sisters, after her bariatric surgery:

I call my sisters. “It might be my imagination,” I explain, “but did you also hear something, after? In the house? A presence?”

“Yes,” says my first sister. “My joy danced around my house, like a child, and I danced with her. We almost broke two vases that way!”

“Yes,” says my second sister. “My inner beauty was set free and lay around in patches of sunlight like a cat, preening itself.”

“Yes,” says my third sister. “My former shame slunk from shadow to shadow, as it should have. It will go away, after a while. You won’t even notice and then one day it’ll be gone.”

It has the effect of a fairy tale there. But not a specific one.

CMM: It was actually was supposed to be “The Little Mermaid.” And there’s the cutting element. But eventually, when I submitted it, they said, “You’ve kind of gotten a little further away, I don’t think that’s legit.” But I like how the story turned out.

LB: I see what you say, because there is that sense of what you’ll sacrifice, the self-mutilation in order to get something.

CMM: Yes, but it’s pretty deep in there. I only tell that it came from “The Little Mermaid” as a little trivia fact, because I don’t think of it as a retelling anymore. I feel it got away from that sufficiently.

LB: But the prompt worked.

CMM: But the prompt worked. Exactly. And I had another story “Help Me Follow My Sister Into the Land of the Dead” in an anthology called Help Fund the Robot Army and Other Improbably Crowdfunding Projects. I’d already been thinking about a Kickstarter-shaped story, so I saw this prompt and thought I could use the hundred bucks that I’d get paid. I sat down and I wrote it pretty quickly, because it just took that little kick to go, “Okay, cool.” So sometimes the prompts actually help me. But at this point I’m too busy to do too many of the ones I get sent.

LB: I was thinking about how in your stories you’ll use place in such a way that it feels contemporary, yet also strange. For instance, “Real Women Have Bodies” has the mall, which feels like a real mall, and yet at the same time it’s at the border of the uncanny, and so is the motel at the edge of town. The story begins:

I used to think my place of employment, Glam, looked like the view from the inside of a casket. When you walk through the mall’s east wing, the entrance recedes like a black hole between a children’s photography studio and white-walled boutique.

And we’ve been there, but you open up its hidden possibilities. We can recognize a place as contemporary or near-contemporary, and at the same time it is being made timeless. I was interested in how you’re choosing to do that. For example, not in that story, but in “The Resident,” you’ll include a geographical detail but use that technique that’s in 19th century fiction where you’ll say the P______ Mountains, using an initial. Can you talk about that stylization? What would you call that?

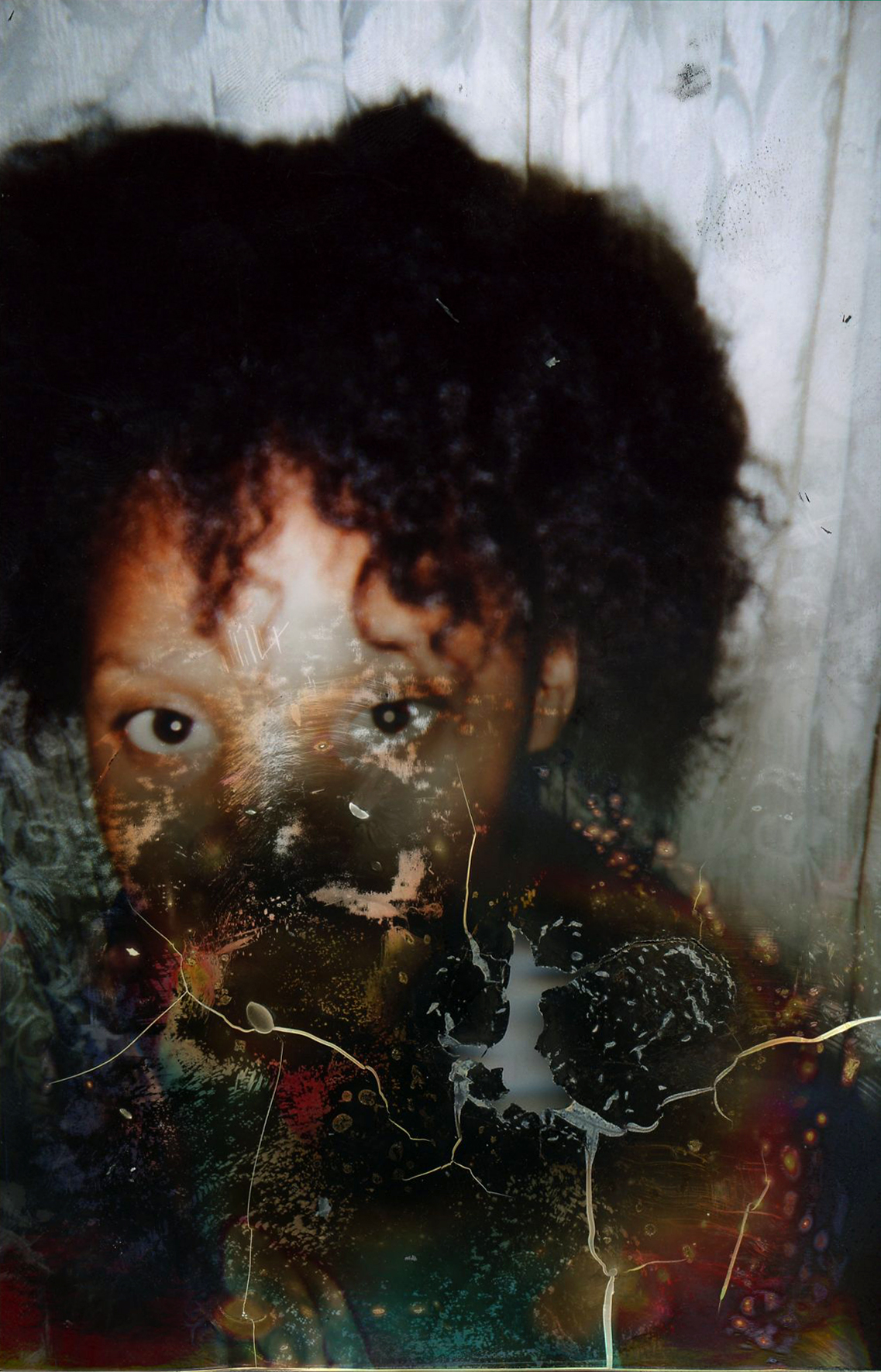

Amanata Adams, Cracked, image courtesy of YoungArts

Amanata Adams, Cracked, image courtesy of YoungArts

CMM: I think it’s called a literary redaction or people call it the “Dostoevsky Dash.”

LB: They used it in the 18th century in gossip in newspapers as a way to avoid libel.

CMM: Exactly, exactly. And I think there are many different reasons that gets used. It could be used for a sense of verisimilitude, implying this could be near your house. “The Resident” had this old-fashioned feel to it, and I thought it would be to fun to try that technique in that story.

As for “Real Women Have Bodies,” those major set pieces, the mall, the store, and the motel, are all places I have physically been. That store, Glam, literally existed at the Coral Bay Mall in Iowa City. I walked past it. It had black walls. It was called Glam. I thought, Well, there you go.

LB: It’s a great name for it.

CMM: It’s great, right? And then the other mall details— I worked at a mall as a teen. So a lot of those places, like the Sadie’s photography studio, I worked at a place like that.

A lot of that is straight up taken out of my own life. And then the motel— One time I drove from Iowa to Pennsylvania for a holiday when I was in grad school, and I stopped at this terrifying motel in Ohio somewhere. It was frozen, this frozen tundra with a trucker motel and a bar, and I’m straight up just ripping that off my own experience.

LB: And yet at the same time, because it’s taken out of all the other context of explanation, it has the feeling of mystery and spookiness.

CMM: Yes, but all those places already had that. I remember being in that motel and thinking this is definitely haunted. I don’t actually believe in that sort of thing, but it had this feel to it, and a lot of places for me have that liminal, edge-of-reality feeling.

LB: So here in Miami we are at the edge. Every minute you’re feeling at the edge of things, even though obviously regular-old real life goes on. But there’s always a sense of being at the edge of America, the edge of the Caribbean, the edge of Latin America, and there’s also the water’s edge.

CMM: And I’m sure, after all the hurricanes, it’s like the edge of existence, right?

LB: Yes, we all faced it, and our threat moved around from the east coast to west coast of Florida, and up the middle. And I would contrast it — I think you’re from Pennsylvania, and I’m from NJ — and there is a sense of solidity, even though it’s not solid, necessarily, but there’s a resistance to change because it was settled so much longer ago than Miami.

CMM: But I feel like Pennsylvania is actually also a weird liminal place, because it’s not quite the Midwest, it’s not quite New England. But I see that there the feeling of liminality is from the place being many things at once, while here it would have that feeling of being on the edge of something.

LB: The liminal also has the sense of both possibility and loss built into it, which I think is in your work. There are many moments of crossing thresholds in some way, and a lot of times those have gains and losses intertwined with each other. And the physicality of the body, which is in your book’s title, supposedly solid yet always changing, and the world, too, as a body that’s shifting or shiftable.

But that leads me to another kind of doubleness, because, reading your work, I thought a lot about the way in which we’re pulled into situations with a lot of sadness, but the stories themselves are full of wit.

CMM: Yes, I think humor and darkness exist in tandem with each other and heighten each other. I never thought of myself as a funny writer, but people would say that a lot of these elements are very funny while they’re very dark, and it makes a lot of sense.

LB: I was looking at the end of your story, “The Husband Stitch,” which is based on the short horror tale “The Girl with the Green Ribbon Around her Neck,” which you’ve set in our familiar American world with teenage sex, marriage, maternity, while keeping the element of the green ribbon around her neck which must never be untied or removed, the one thing, despite surrendering so much else, that she will not do for the husband, who can’t give up wanting her to, so we feel the horror in how possessiveness can destroy what is supposedly love. At the same time, there’s her voice telling it, and right when we’re dreading and anticipating the final moment, which is, we know, going to be grotesque, she says:

If you’re reading this story out loud, you may be wondering if that place my ribbon protected was wet with blood and openings, or smooth and neutered like the nexus between the legs of a doll. I’m afraid I can’t tell you, because I don’t know. For these questions and others, and their lack of resolution, I am sorry.

And that’s very funny, that moment of direct address. So we’re laughing, and then she says what she does experience. And, too, the voice outlives its own body. Which of course is another thing that stories do, because the voice is always outliving whatever happened, and it can go on and keep being read and reread.

This also reminds me of your novella “Especially Heinous,” which takes the form of a series of invented episode capsule summaries for Law and Order SVU, because it’s about the perspective of being watched and watching. So reminding readers that they’re reading gives some distance, and at the same time you’re pulling people right back in. So can you say whether that’s something you’re very conscious about, the reader reading?

CMM: Yes, because I really love that when I’m reading something. It’s weird because some teachers or writers would argue that, oh, you don’t want to disrupt the dream of the story, and there are different explanations of that, but I do think that some of the stories require it. When you have a story about stories, inherently, you’re already commenting on the reader and the process of that story. Both “Especially Heinous” and “The Husband Stitch” are about stories. And so it doesn’t make any sense to be immersed in the dream, because the reader is a participant in the story as much as any of the characters. It makes sense that one would do that.

LB: You have a memoir coming out next?

CMM: I do. In two years. Due to my publisher next year and then coming out in 2019.

LB: That’s not even two years now. We’re almost in 2018.

CMM: It’s true, it’s true. I thought that the pub date for “Her Body and Other Parties” would never come when I sold the book two years before. And then here we are. (Laughs)

LB: And it came out this fall.

CMM: October 3rd.

LB: So that’s been quite an amazing experience.

CMM: Yes, this has been a surreal month and a half in my life.

LB: Because of course it was a finalist for the National Book Award. So you actually had it come out with that already there in front of you.

CMM: Which was unexpected and tremendous.

LB: Are you exhausted?

CMM: I’m very exhausted. But it’s not bad. It’s just a lot of energy, and I’m teaching also, so it’s even more of an energy drain in every direction.

LB: So it’s one of those wishes come true tales.

CMM: (Laughs.) Right, exactly. But it’s hard to complain.

Lynne Barrett is the author of the story collection Magpies and the handbook What Editors Want. Her recent work can be found in Mystery Tribune, Necessary Fiction, and Just to Watch Them Die: Stories Inspired by the Songs of Johnny Cash. She is editor of The Florida Book Review.