Brookhart Jonquil: in a Perfect World

Rene Barge: Relay

Cara Despain

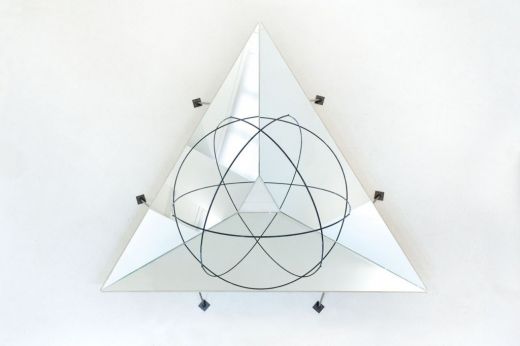

Brookhart Jonquil, In a Perfect World, 2013. Mirror, wood, fiberglass rods, steel. 7ft 8in x 7ft 8in x 2ft 6in. Photo courtesy of Emerson Dorsch.

The navigability of a space is crucial to your experience in it. The way light enters and exits, how sound travels and how visitors are guided through all play into the functionality and aesthetics of a building designed around the sensory experience. The newly renamed and remodeled Emerson Dorsch Gallery’s co-owners and architectural collaborators clearly considered these factors and articulated a thoughtful, sleek new home inside the Wynwood warehouse they have occupied for over a decade.

Consolidating the formerly expansive rooms to offer one large main space, a project room and a large entry area, the new gallery succinctly proffers an inviting and professional interior that is well- suited for the quality of work it houses. And it’s not even a windowless white box—natural light pours in the modest panoramic windows and all-glass entry along the east-facing wall, allowing a rare green courtyard to be visible from inside. “It’s nice,” said co-owner Tyler Emerson- Dorsch, “for people to have an opportunity to transition and prepare for viewing art rather that just entering abruptly into the middle of an exhibition.” It does make a difference. After traversing the pleasant yard area and entering through the foyer on the side, visitors are first greeted, presented with information and given a more natural sense of the space they have entered before they assess the work. At the very least, their eyes can adjust from the intense external daylight to the also intense internal bright whiteness of an art space before making critical assessments. This mindful guidance is disarming and underscores the gallery’s newly reinforced identity as not only a professional commercial gallery but also a place for gathering and exchange among community. Though often galleries are seeking to expand, here downsizing the exhibition spaces seems something that will prove to be advantageous. Not to discount the charm of our familiar cavernous Wynwood warehouses, but it is nice to almost forget you are in one for a moment.

How apt, then, that the two opening exhibitions should so keenly and directly deal with the effects of space and non-space. Rene Barge’s piece in the project room, “Relay,” depends on the tension and curvature of the utilitarian materials to be perceived both visually and audibly. Using custom-made transducer systems the sculptures, or rather the negative space created by their simple arrangements (which change configuration over the course of the show), communicate with each other to create unique sonic exchanges that evolve and change with each relay and each different set-up. The visible forms, thin-gauge sheets of wood forced into place by Dyna Bend exercise elastic whose color intentionally evokes Christo’s “Surrounded Islands,” (1980-1983) are

the physical enablers for the subtle and sensitive audio. Modular and self-contained, they create an insular system that seemingly sustains itself indefinitely. The isolation of the project room allows the opportunity for effective interaction with the piece. Though appearing as a blunt test of durability, the dual constructions also carry a kind of delicacy that might be missed if visitors are reticent to penetrate the boundaries of their interiors to listen. Though being drawn in to the microcosm is part of the point, they struggle some-what to be alluring.

Brookhart Jonquil’s solo exhibition In a Perfect World presents another layered microcosm and a macrocosm simultaneously. Drawing from Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Maps and Platonism, Jonquil’s faceted constructions elicit as many reflections as their mirrored surfaces. Similarly hinged on tension, they begin using the same spherical forms and add different basic shapes that are echoed and completed by angled mirrors on wood and metal supports that are pierced by strained, arched fiberglass poles. Though bound by tense energy they are static— their structural stability implied by their multi-dimensional completeness. Following Plato’s postulation that true perfection in form lays in emptiness or outside of a non-physical reality and abutting that with Utopianism, Jonquil attempts to realize representation of perfect forms using Euclidian geometry.

Many substructures are alluded to in his attempt: subatomic physics, and on the philosophical end of perhaps the same spectrum, the idea that there is some flawless elsewhere that exists outside of material form and matter with all its fickle trappings— such as ever-changing physical states and time. As sculptures, the pieces draw in and also create space, fracturing the environment around them—allowing themselves to exist in that environment, but also beyond it. At the center of each is an exposed piece of the white wall, nearly unrecognizable as such even though it is altered only by reflection. When mirrored from each facing panel, this shape takes on many additional faces and become the nucleus of a whole form which is mostly extant in fictitious space. When standing in front of the works the non-real space appears as good as it’s authentic counterpart and functions as a possible reality. However, we understand it is irrational because the wall is what actually lies behind the sculpture and not this alter-dimension. Here is the discrepancy between visual and physical perception, and between a model for perfection and it’s actuality. Creating a model for motion, dimensions and phenomena that lay outside of our perceptual capabilities means that model will inevitably be an abstraction of the concept it represents. Trying to make visible the structure of an atom, for example, means slowing it down—according to quantum mechanics an electron can be at any point in space within its field at any given moment, but our model wants to plot it in one place or all places for the sake of depicting multiple possibilities. Constructing a model strips a concept (especially slippery ones like perfection or Utopia) of its liminal quality and subjects it to physical limitation and human error. Though beautifully fabricated, Jonquil’s sculptures cannot achieve the perfection with which it is possible to render them in as geometric models, and the mirrors can merely reflect what he has built. Lovely as they are, they are mostly empty space meant to refract our limited notion of an ideal. Among the strange magic multiplicities found darting around in the kaleidoscopic caves it is this reality that is the overarching reflection, and it is what makes the show so acute and exquisite.