- Midnight Thrift

- A New Day Has Come: A Review of Radical Hope: Letters of Love and Dissent in Dangerous Times

ON PINKNESS: The Pink House and its Secret Spatial Heart

Alastair Gordon

Pink to Pink: a 1957 T-Bird Coupe (Ford Motor Co.) parked in front of the Pink House, Miami Shores, (Arquitectonica), 1978 photo: Eric Meola

Pink to Pink: a 1957 T-Bird Coupe (Ford Motor Co.) parked in front of the Pink House, Miami Shores, (Arquitectonica), 1978 photo: Eric Meola

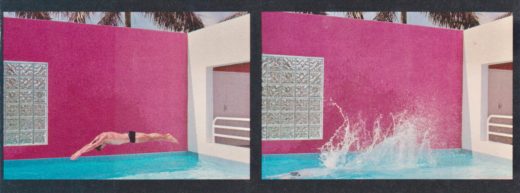

Early studies by Rem Koolhaas and Laurinda Spear (daughter of the clients and still an architecture student at Columbia) reduced the program to essentials: palm tree, lush foliage, beach, egg-yoke sun glued to tissue-paper sky in full-blooded, Endless Summer orange and yellow. The house is almost an afterthought, dropped casually between jungle and sea. A masonry facade is perforated by the oddly small rabbit hole, or so it appears, and there’s a staircase and narrowly enclosed “street” that branches off into seven mysterious chambers. The most incongruous features are two highways that extend orthogonally through either end of the facade. This was not just about sun, water and tropical fecundity. It was about expanding horizons and the mythology of drive-through mobility.

A lap pool penetrates the right flank of the house and stretches to infinity. In theory, one could swim (like John Cheever’s heroic swimmer) from the driveway, beneath the house and out to the edge of the bay and beyond. “He seemed to see, with a cartographer’s eye, that string of swimming pools, that quasi-subterranean stream that curved across the county”, wrote Cheever in his short story “The Swimmer” (1964). Koolhaas is an obsessive swimmer himself. “I swim every day wherever I am”, he said in a recent interview.

Spear and Koolhaas submitted the project to Progressive Architecture‘s annual awards program. A four-person jury met in New York to deliberate. They were intrigued but also befuddled. “It’s not the work of an architect”, complained Paul Rudolph, father of many experimental houses himself. “It’s either very great or very, very bad”, said Eberhard Zeidler, not quite sure what to think. “It’s so much at the edge of absolute disaster, yet it has such fantastic poetry”. Ivan Chermayeff found it “undeveloped” as a building, but successful as a “poetic diagram”, as if a “mad poet has stretched it out; taken the drawings and laid them down like a child’s cutouts.”

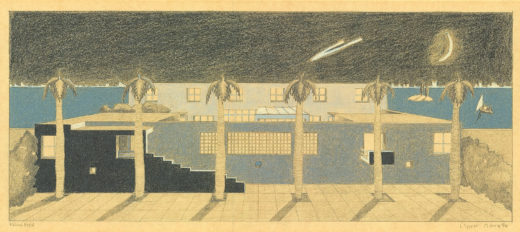

A mysterious porthole in the front facade reveals the aquamarine pool beyond.

After completing her studies at Columbia University, Laurinda reworked the plan with newfound partner and husband, Bernardo Fort-Brescia. (By then, Koolhaas had returned to Europe to finish work on Delirious New York, his “retroactive manifesto”, and launch the Office for Modern Architecture [OMA]).

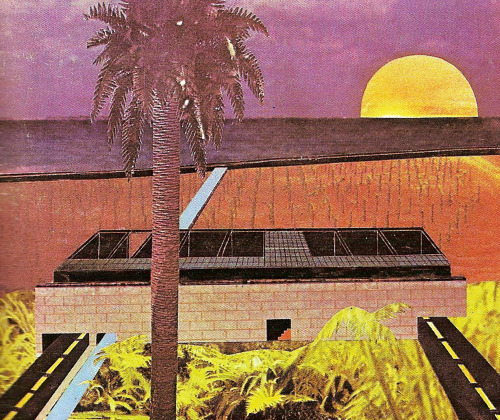

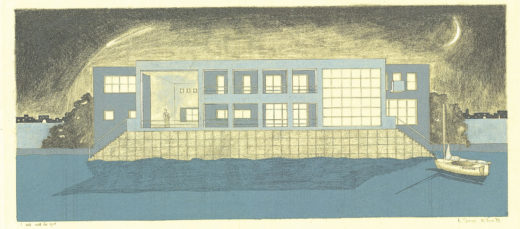

Spear’s renderings for the revised version combine the moody romanticism of Chagall with the hippy innocence of Alicia Bay Laurel’s Living on the Earth. In one drawing, there’s a shooting star and a sliver of moon glowing in the night sky. The house rises out of a cornflower-blue bay, a dreamy scaffolding, planar with square, punched-out openings and backlit screens, as in Kabuki theater. A sleepwalking woman stands by the railing and gazes out to sea. (Is this Spear herself?) There are echoes of Giacometti’s “Palace at 4AM” (1932), but this dream house is inundated by water with a sailboat moored to the banister and steps descending into the bay at either end. A faintly penciled caption below reads: “I will wait for you…”

As built, the Pink House is a progression from water to water, a color-coded conversation between lap pool and Biscayne Bay, setting up a sequence of rhythms, reflections and alternating syncopations, beginning at the 115-foot wide facade and proceeding through other layers and colored foils, from blushing rose on the first wall, to wild flamingo on the second, to a paler, conch-shell pink on the two-story wall of the main house. “The alignment of colored planes seems to evoke the idea of screens to protect the nucleus of some secret spatial heart”, wrote Fulvio Irace, an Italian critic who wrote the first deep analysis of the project (“The Dream of a House”, Domus, January 1981). But where, exactly, does this secret spatial heart hide itself?

There are subtle hints of numerological symmetry throughout. Six square windows in the main house correspond to the six palm trees in the front courtyard. Three panels of translucent glass block are rippled like water and suffused with sea-flecked light. The foundation plinth was not a neo-classical affectation but arose in response to a flood-control law that required the first floor to be eleven feet above grade. The entry staircase leads to an open-air terrace that, in turn, surrounds a narrow sixty-foot-long pool which assumes a central role and confirms the project’s conceptual bias towards wetness.

The first-time visitor can preview this underwater “chamber” through a luminous eye that gazes out from the center of the main facade in cool chlorinated blue. It is round like a porthole or camera lens and is the true metaphysical entry to the house, suggesting other ironic subversions of the American Dream: Cheever’s “quasi-subterranean stream”, David Hockney’s homoerotic pool culture, or Joan Didion’s “subaqueous suspension”. (Both Jay Gatsby and Joe Willis, narrator of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, are found dead, floating in their respective swimming pools). The aquamarine lens is also a peephole for watching unsuspecting swimmers–what Irace refers to cryptically as the “voyeur’s ambiguous game”–a ritual that evokes Miami Beach’s early days of Aquacade ballets and glass-bottomed boats. Morris Lapidus designed an underwater bar at the Eden Roc Hotel with a similar porthole (but much larger) for watching scantily clad mermaids dance in dreamy syncopation.

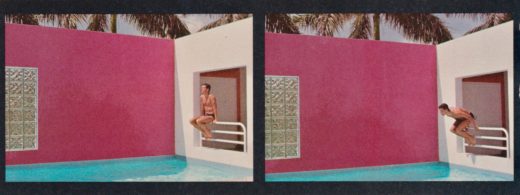

The house was completed in 1978 at a cost of $277,000. While some of the early responses were negative—”NEIGHBORS SEE RED OVER PINK HOUSE”, ran a headline in the Miami Herald and Councilman Ralph Bowen grumbled something about the color being “inappropriate”—but most reviews were enthusiastic. Besides design journals like Progressive Architecture and Domus, the house quickly rose beyond the insular world of academic architecture and became a pop icon, featured in mainstream publications like the New York Times, Vogue, Time, Newsweek and House Beautiful. It was also a favored location for fashion shoots and TV commercials.

The house became a popular location for fashion shoots and TV shows like Miami Vice. Bruce Weber shot a male model in the pool at the Pink House for the February 1980 issue of Gentleman’s Quarterly (GQ)

The Pink House embodied a certain moment and mood: European rationalism cross-fertilized with the tropical surrealism of Miami. Everything about the place—the color, the pool, the translucency—seemed to exude a simmering, barely sublimated sexuality. It also represented a crucial turning point for the city at large. Suddenly Miami appeared to have a culture that went beyond retirement plans and palm trees, a culture that was edgy and slightly dangerous, with fast cars, cocaine cowboys, cigarette boats and outrageous architecture.

Early collage study for the Pink House, c. 1973

Land-side facade, Pink House, rendering by Laurinda Spear

Bay-side facade, rendering by Laurinda Spear

Alastair Gordon is an award-winning critic and author who has written regularly about the built environment for the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. His critically acclaimed books include Naked Airport, Unfolded, Weekend Utopia and Spaced Out. He teaches critical writing at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, and is the architecture critic for the Miami Herald.