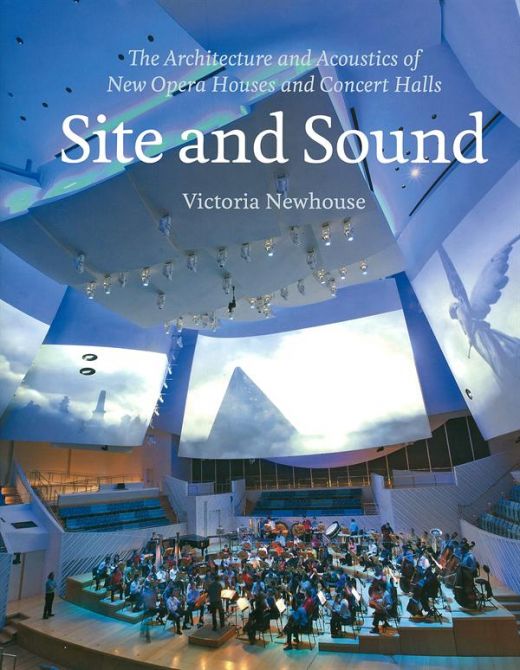

The interior of the New World Center, bathed in moody blue lights during a performance, with projections of clouds and aural objects against the sail-like forms of the ceiling, is on the cover of Victoria Newhouse’s recently published Site and Sound: The Architecture and Acoustics

of New Opera Houses and Concert Halls. The orchestra is not formally dressed, but in jeans. People mill about; the audience is gone. The scene is most likely not even that of a rehearsal, but of a class in session. This reflects New World itself, as a symphony and an orchestral academy in one, and a very public place.

Site and Sound is to concert halls and opera houses what Towards a New Museum, one of Newhouse’s earlier books, was to museums, bar none: a thorough and insightful retrospective of a peculiar moment in the recent past when a specific building type became an international symbol of the contemporary city. Site and Sound documents a global boom in performing arts center construction, when concert halls reached a period of extreme vogue and at least 360 new halls were built in the United States alone within the last few decades, including the one at New World, and the Arsht Center’s two halls.

Newhouse’s new book is a gracious tour through the history of concert hall architecture, the current state of the craft, and its experimental future. It is written as a retrospective of recent history, but it takes the long view. It is insightful and nuanced, yet relaxed and rather stately, like the woman herself. With an unlimited budget of time and money, Newhouse, who is the wife of a magazine tycoon, has seen multiple performances in each hall she discusses.

She takes her time, exploring each hall’s architecture and acoustics in depth. With the advent of halls designed for a multitude of uses, or even genres of sound, acoustics can never approximate the perfection of a single hall devoted to the genre of a single composer or royal court. Thus the greatest success of a hall must be measured in the sum total of its visual, audial, and tactile experiences; in its full ambience.

Half of New World’s land is devoted to a park and public SoundScape concert lawn by the Dutch landscape designers West 8, with advanced video projection and sound technology. More than half of the Frank Gehry-designed building is an atrium filled by a pile of freestanding rooms taking various forms, subtly divided between public and academic uses. The hall is only one destination in the center’s series of spaces.

Newhouse’s conclusion on the New World Center, that “these heady ideas and the heady concert hall stemming from them are off to a promising start,” is modest, but why would she pick this building, with people in jeans, for the cover? Unlike the Arsht Center, which she chose not to include, New World Center is a unique and successful public place, embodying the evolution of the art form.

New World, along with all the other concert halls in Newhouse’s book, exhibits the power of site for the experience of sound in the ways that sound is experienced today. Sound can no longer, of course, be sustained as an elitist pursuit, as can still be seen in the citadel-like design of New York’s Lincoln Center before its more recent renovations. These new buildings are presented as public possessions, and as places democratically accessible. She, the tycoon’s wife, is no longer the primary recipient of the music hall’s gifts.