The work of Claudia Fernández installed at the Museo Experimental El Eco in Mexico City.

HUNTER BRAITHWAITE (RAIL): So you studied Art History in Mexico City, right?

PAOLA SANTOSCOY: I did.

RAIL: But then you got your M.A. in San Francisco?

SANTOSCOY: Yes. In 2007, I went to San Francisco to get an M.A. in Visual Criticism at CCA (California College of the Arts). At the time, I had already been working in museums or independent spaces in Mexico for seven or eight years. Actually, Tobias [Ostrander, PAMM Curator who worked with Santoscoy at Museo El Eco and the Museo Tamayo] was the one who suggested not to do an M.A. in Curatorial Practice, but to really try to think of something else because I was already working in that practice. So I chose visual criticism. It was really a very good choice because I had time to focus on writing and not think so much about exhibitions.

RAIL: Sure.

SANTOSCOY: When you start working young, as I did in institutions, your writing responds to the formats that are needed within that professionalization of art. You either write a wall text, or a catalogue text, or a review for a magazine…

RAIL: …Or a press release.

SANTOSCOY: Or a press release. Outside of those forms, it’s very difficult to think of a different structure of writing. So I asked myself, “Okay, if I don’t write for something within this format then what can it be, what can I write about if I just want to write about art?” Which seems like a very simple question.

RAIL: Did you experiment with different formats? I’m always sort of thinking of ways to sort of escape the 300-word exhibition review or the press release.

SANTOSCOY: During the M.A. there were different courses that were specifically about writing, and creative writing, critical or something and that helped a lot, but more than that I think it was the moment when you go back to what you do and try to respond differently every time.

RAIL: Could you just tell me how those two different pedagogical systems differed in your experience studying Art History in Mexico and then doing the M.A. in the United States? Were they similar?

SANTOSCOY: No, I think they were very different. First, there’s only one university here that has that B.A. in Art History. I think next year UNAM [National Autonomous University of Mexico] is opening a B.A. in Art History. But for a long time there was one place to study Art History, the Ibero-American University, and I felt that the curriculum of that B.A. was a bit old. I think we all did, even the faculty members. It was a moment when they were trying to really shake things up and change it a bit because the Art History department had very little exchange with the art scene, with what was happening outside, with alumni, with the real world.

RAIL: Going on that exchange between the art scene and the Art History department, Mexico City has one of the longest histories of any city in the hemisphere, but I’ve been struck by this narrative of the emerging contemporary scene—all of these art spaces popping up in apartments in La Roma or somewhere. Could you tell me a little bit about the connection between emerging contemporary art the historical wealth of the city, and how that informs what you do?

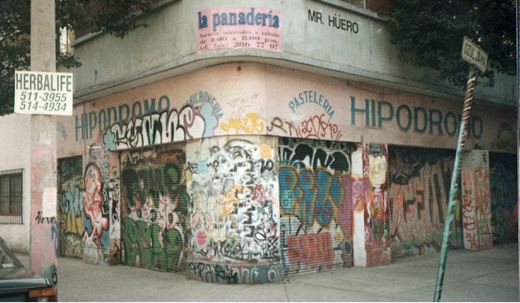

SANTOSCOY: The scene has changed a lot in the past ten years. I finished Art History in ’99-2000. That’s when I started working at an alternative space, at the time that was called la Panadería, one of the spaces in the ‘90s and early 2000s that was an important point of reunion for younger artists and the younger generation. But I think at the time it was very clear how the fact that having an alternative space was really an alternative to the institution, which wasn’t very open to new art, younger generations, or other types of experimentation or formats. Also, this model of alternative spaces was pretty much copied from Canada and the States.

These were artists that studied abroad in the ‘90s, came back to Mexico, opened these spaces, and started shaking things up in the scene. I think right now, that idea of alternative space doesn’t work the same way as it did 10 or 15 years ago—not only in Mexico, but in other scenes as well. I think here, for me, its very clear how really these independent initiatives have become co-ops, collectives, groups of people that decide to fundraise for projects in different format. They are not necessarily against the institution. Many times, they are working with the institution, collaborating within that same structure. Also, more and more institutions are reaching out, not to absorb these practices and institutionalize them, but to try to find the way to be in the middle and have this activity around you. El Eco is a very interesting example, because this is an institution that is an experimental museum by definition.

RAIL: It was founded in 1953. So it has a history.

SANTOSCOY: A very long history, a very interesting one also, because in the ‘50s it only functioned for three or four months.

RAIL: Really?

SANTOSCOY: Yes, this was a project that was very visionary at the time. The building and ideas are of late Modernism. In Mexico, Modernism came pretty late in relationship to Brazil, for example, or to other countries in Europe and other places.

RAIL: Why do you think that is?

SANTOSCOY: Muralism was very strong in the beginning of that century. Throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s, it was really the official art movement. I think it was very difficult for artists to create a break with that, which happened early on, but also for Modernism to become something that was embraced more ambitiously.

RAIL: Is there a political component to that? As far as Muralism’s engagement with the left?

SANTOSCOY: I think so, but just to jump back, when I was talking about the alternative spaces, I was thinking about how also in the ‘90s we were still under the PRI [Institutional Revolutionary Party] government, which we are again now. At the time they were in power for more than 70 years. This was the soft dictatorship that a lot of people talk about in Mexico, so being against the institution, being against the official kind of political precision in terms of culture and arts was important in the ‘90s and for these alternative spaces. I think now, although we’re back with PRI and some of us are very unhappy about that, there was a period where that changed and things moved in terms of cultural policy. I think institutions have definitely developed since. They’re not seen like they’re stuck, kind of in a non-flexible position.

RAIL: You had mentioned earlier that in the 1990s, alternative spaces worked differently than they do today. Are they working today? Is the mission of the alternative space viable in Mexico City? Can it exist outside of the institution? Or outside of funding structures?

SANTOSCOY: It’s difficult. I think they are pretty much within the system. They just choose different ways of funding their projects, of presenting themselves, of producing. I think also, the cultural infrastructure of Mexico City has grown a lot. The Fundacion Jumex now has a museum, but 10 years ago it was just starting to collect. They were responsible, together with the city and the cultural ministry, for sending a lot of people abroad to study. I was one of them. It was a big generation of people studying abroad with money from this foundation and from the cultural ministry and then coming back and re-thinking the way both institutions or just art practice can be.

One more thing. I think artists have more options today then they did 10 or 15 years ago in terms of producing projects. There are many different formats, many different possibilities—not only the commercial gallery, the institution or the alternative space. I think now you have a broader span of possibilities to realize a project. It can be from a talk, to a walk, to a huge production of a film, or a piece. It can be anything. And there are different groups of people or institutions or associations that might be able to facilitate that.

La Panadería

SANTOSCOY: The National University is playing an important role in the art scene now. They also in the past 10 years have renewed a lot through their mission, and their commitment to producing not only art but knowledge, and by being in the scene. The University has six museums. One of them is El Eco, which they bought in 2004 and restored to how it was in the ‘50s. They have the only public collection of Mexican contemporary art. The sad part is you cannot go to the museum and see that collection; it’s not always on view.

RAIL: One of the hurdles we have in Miami is trying to create an art world without a strong academic background. Are most of the artists that practice here educated here as well?

SANTOSCOY: Most of them, or abroad. Right now also, there are pedagogical projects and experiments outside of the official universities. There is SOMA, which is a very good example because it’s also a group of artists. The artists behind SOMA are also the artists that were behind La Panadería in 1994. They were the ones opening this alternative space that at the time made sense as an artist-run space and an artists project. Then 10 years, 15 years later, they are embarking on a project that’s very different. It’s a pedagogical project, but it’s run by artists. It also involves inviting people from abroad coming here. There was another project for some time called Teratoma, which was a group of mostly curators, art historians, and philosophers who came together to do projects together.

RAIL: When was this?

SANTOSCOY: 2003 to 2007, I think. Teratoma had the first attempt of a curatorial practice program in Mexico at the time. A curator named Pip Day, who had been living in Mexico for a long period was in charge of this program. It was a short program I think—nine months, or 10 months—with a group of people, and it was focused on curatorial practice. It didn’t have any academic recognition, but she would bring people to speak. She would organize workshops for this group. Now, there’s a masters degree at the National University in curatorial practice, which is very new. It’s only two years old.

RAIL: Can we return to El Eco?

SANTOSCOY: In the ’50s, as I said, it was a very visionary project because it was a museum with no collection, an experimental museum. It was a privately funded project. The project of the Museum of Modern Art or the Museum of Anthropology, they are from the ‘60s. In the 1950s having this experimental museum was definitely visionary. It was meant to be interdisciplinary and it was really a project space. But the museum had a bar, and also the possibility of having a small commercial gallery on the second floor, which didn’t happen. We don’t know if that would have happened.

RAIL: Does the bar exist today?

SANTOSCOY: Yes, but the bar is not open everyday. Since we are a venue of the University, we are not allowed to sell alcohol.

RAIL: For a bar?

SANTOSCOY: Yes.

RAIL: That’s a problem.

SANTOSCOY: On the university campus, you cannot drink alcohol. That’s a legacy of the ‘60s and the student movement when they prohibited drinking on campus, which is ridiculous, I think. We do have cocktails at our openings, we are just not allowed to sell them. So we use the bar for all the openings and those things, but we also have a program that happens every two months. My dream is that it can happen every week. At least once a week, where we open the bar from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m., and there’s a host that we invite and that host decides the guest list, and what were drinking, and the music. But it’s still part of being a project. We don’t go as far as I would like to, which is actually having the space just opened for a drink, where the locals could also be part of that and not having the guest list of the museum.

El Eco in the ‘50s opened for a very short period of time because the patron who commissioned the building died of a heart attack at 37. He died in debt and the family took over to try and start paying the debts. Goeritz was out of the picture, and so this project for the experimental museum stops at that moment. The space became a restaurant afterwards so his family starts to pay for the building, then a bar, one of the first gay bars in Mexico in the late ’50s. It was very successful. Then in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s it’s a theatre space. The different theatre groups that passed through modified the architecture. So by 2000, the original architecture of Goeritz, which was a sculpture more than a building, was gone. It had to be completely restored. The University bought this building and restored it, to reopen it in 2005.

Luckily, [they did this] with the idea of recovering its original purpose and saying, “Okay, this is still the experimental space, its not Mathias Goeritz’ mausoleum. It is a project space.” Today we have the responsibility of trying to answer what an experimental museum might be. Behind Goeritz’s ideas there was, for sure, the idea of the total art work. Goeritz wrote a manifesto called Emotional Architecture Manifesto when he did the building. Right now some of those ideas are still important and interesting, but to think of experimental, curatorial or artistic practice in the present means very different things. We try to approach it through experimenting with formats—with actually how an institution can relate to the outside and create different collaborations, where other voices can come in and really allowing artists to think of different structures.

RAIL: To go back to the art writing. How does writing inform your curatorial practice and vise versa? Do you see your role as especially authorial? The Nature of Things comes from Lucretius, it’s literature playing out as an exhibition.

SANTOSCOY: I don’t see myself as an art critic, that’s something I would say. I think that’s a role that entails a lot of responsibility, not that I don’t want to have, but responsibility in terms of consistency, writing often, having an editorial voice, and having an opinion that you can follow through. For me, an art critic is someone who you can follow, in terms of what they are thinking and saying. I think my contributions have a more organic and unorganized span in terms of my writing for articles about something that I’m interested in, or a project that I’m working on, to an interview with an artist, to a review about an exhibition, or even creative writing in more experimental magazines that don’t address contemporary art directly. I think that’s my way of contributing to the discussion in terms of art practice. The writing is pretty much where you can speculate something that you might later take on.

RAIL: Which writers would you say are influential in this mode of organic, unorganized contribution?

SANTOSCOY: There’s a woman in Brazil that I like a lot—a psychoanalyst who writes about art, called Suely Rolnik. She has written a lot about art, she has even curated some shows, but she’s a psychoanalyst….Her writing comes from a place that is very different from structured, academic art writing. Then there is this woman that I really heard about, or read about very recently, about two years ago, from Lebanon. Etel Adnan is a writer, an artist, and a poet, and she has very beautiful texts about art and life.

RAIL: I didn’t realize she was a writer. I love her paintings.

SANTOSCOY: She has amazing poems. She has a very beautiful, beautiful text called The Cost For Love We’re Not Willing To Pay. She ends up speaking about art really in that text.

RAIL: Do you think curatorially, when you’re actually staging an exhibition and putting objects in a space, or do you come from somewhere else? Perhaps a more literary conversation?

SANTOSCOY: Not always. I think I come more from a conversation with the artists themselves.