Reading List

“Music and Information Theory” and “What is Value and Greatness in Music,” Leonard B. Meyer, Music, The Arts, and Ideas (1967)

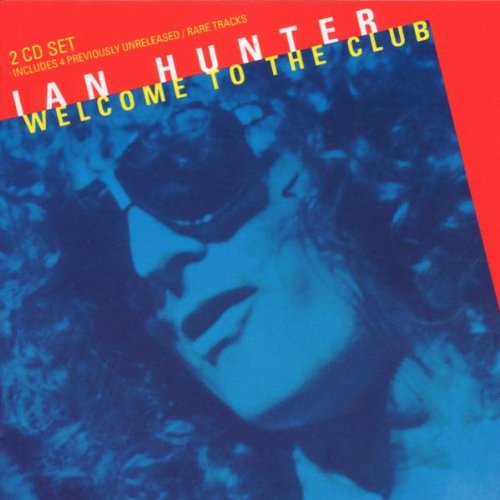

Playlist

“Once Bitten Twice Shy” written and performed by Ian Hunter

“Irene Wilde” written and performed by Ian Hunter

“Goodbye to Love” by Richard Carpenter and John Bettis, performed by The Carpenters

“At This Moment” written and performed by Billy Vera and the Beaters

“Just Once” written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, performed by James Ingram

These are all songs that I like for one reason or another. Now, what I want to talk about today is writing pop songs. I did this for many years, and I had some cuts and I had some hits, and I had some non-cuts and some non-hits—more of those than the previous. I lived in Nashville and LA, so I know how those songwriting scenes worked. I can describe my career as a songwriter as Billy Joe Shaver described it to me once, “I can take one ’a yourn’ and sell it, and you can take one ’a mine, and not.” Billy was very proud of his abilities to appear subservi-ent and hapless—also he had three fingers cut off in a saw mill accident, and that really helped.

My Dad played in bands so I grew up with music of this sort. I think the first thing I learned all the words too is Rogers and Hart’s “Mountain Greenery”—In a mountain greenery /where God paints the scenery / just two crazy people together / While you love your lover, let /blues skies be your coverlet / When it rains we’ll laugh at the weather—because I liked the eu-phony. I sat in the tree outside the window of our living room and played it over and over until I got too tired and came down. Then I was in a number of bands—same people but we kept changing the name. When I went to school I thought I was a poet and liked formes fixes—Villa-nelle, Rondeau, Virelai, all these strict French poetic forms. I was very happy about it, but you can’t write villanelles forever. Now, what is a villanelle? Look at the repeating structure of Dylan Thomas’ poem, Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light—that is a villanelle, a beautiful form.

There is a sort of a prime distinction between writing songs and writing poems and it’s very simple: when you are writing a poem, you are trying to write something which is eccentrically your own. But, if you’re writing a song, you’re trying to write something that is eccentrically everybody. In other words, you’re trying to make a song people can whistle and hum and think, totally man! That kind of public confirmation is what songs are all about. That means that what you are doing is struggling toward some generalized cultural norm—having done that you hope everybody will like it, and they will buy your record, and you can go live in West Palm Beach.

Big mistake in my life: I was in Nashville writing essays about music, writing about art, and writing songs. And I decided that I could be a B+ songwriter, but I could be an A+ art critic. At that time I was so medicated I thought it would be best to write art criticism about things that are really hard and confusing. Now, I was wrong. Because I did not take into account the difference in income between a B+ songwriter and an A+ art critic—being a B+ songwriter means you get to live in West Palm anyway, and nobody is going to bother you.

But the point is, the crowds are different. Most of the people I know who are songwriters, are really crazy people. They are non-joiners. And yet, all they want to do is write nice stuff like “Gentle on My Mind”, or something like that. Whereas, “serious” poetry is usually written by people from Connecticut, who have attempted to distinguish themselves from all the other serious Connecticut people they know by writing things called “Jezebel at Four Fifteen.” And so, what I mean is, you have an inversion: you have crazy people writing pop songs, and boring people writing poems. And a simple survey of the poems and pop songs available should make this clear to you. Now, these are equally difficult. It is really hard to write a song that everybody likes. And it’s difficult, too, to write a poem like “Jezebel at Four Fifteen”. And so you try to find the place to write what you like.

Now, there are different kinds of pop songs. There the songs that you write with a band: where you all stand around in the room and finally come up with the base line and play that over until someone finally says, Hallelujah, I love her so!, and then you move on from there and eventually you’ve written a song. Most good Rock and Roll songs are written that way.

Most songs are written from little fragments—three or four notes—a riff, and a piece of lyric—that’s the heart of it. You have a riff, or you have some words that you want to put into it, like, My baby is taller than Jerry—or whatever you want to write. So you build your song around these kinds of armatures. And, I find it best to write the song with someone else. Because, when you’re writing a pop song, you’re looking for the maximum possible audience, so it’s best to write them with two or three people.

Now, you’re trying to write about two minutes and forty seconds to a three-minute song—the standard form of a pop song. Do ya’ll know Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony? That structure is A-A-B-A, which is coincidentally also the structure of most pop songs. Even if they’re not arranged particularly well, that is still the structure. Most pop songs have verses, bridges and choruses. You can arrange these units in any number of ways. The simplest way is: two verses—sixteen bars in all—and a chorus. So you have a verse and a chorus, a bridge and a chorus (and that’s a release, in other words it’s something different than the chorus and the verse), then it’s just chorus, chorus, chorus, chorus, chorus. The idea, of course, is to make a little machine—and that is the best that you can call it, a little machine. You have a verse and you repeat the verse, you have a chorus and you repeat the chorus, then you play the bridge, and then you play the chorus, and then you play the chorus, extending into infinity.

I’ll quote my old friend Tom Dowd, who is a pretty good record producer—he produced everything from Lynyrd Skynyrd to the soundtrack for Saturday Night Fever. Tom had one rule: Don’t bore us, get to the chorus. The idea is to make the chorus come faster and faster. So if I say: first verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, chorus, chorus. What that amounts to is a situation in which the chorus, the hook, the thing you want to come back to every time, happens sooner and sooner. If you’re speaking in Pavlovian terms, you’re saying verse, verse, cookie. verse, cookie, bridge, cookie, then cookie, cookie, cookie—this is the way you want a pop song to work. You want to start off by teasing them with the cookie. Then you want the cookie to come more and more rapidly so you are comforting their desire more and more rapidly—and that is why a pop song is a little machine of desire. Now some of them are brilliant and some are really bad. When they’re brilliant I find them breathtaking.

You have to write all this shit. Now, where do you start? I used to write with two guys, Jimmy Rushing and Ernie Rowell, who was bass player for George Jones. It’s best to work with three people: one person writes riffs, I write lyrics really fast, and somebody else writes harmony, and then you can write a song in ten minutes. The problem with writing a song in ten minutes is that you’re probably plagiarizing something. I remember driving around in Nashville and, Holy shit, I had this beautiful melody!—it was so good. I went running home to tell my girl-friend Marshal Chapman, and she said, Gee Dave that is really great, but that’s the tune to Tom Waits singing “Ol’ ’55.” This actually happens all the time: you’ll have sat down and written a song, and then you’ll have spent the next two weeks listening to every song you can find to figure out where you stole it. Because there is a kind of mind-meld going on, on Music Row or on LeBrea or wherever the songwriting scene is.

So you do that, and then you pitch it. Or if you’re lucky someone will say, Write a nice song for the Judds. And I did write one for them called, “If you Cross That Bridge You’ve Gone

Too Far”—because that was the instruction to get to everybody’s house in Nashville: You take the 347 right past the 7-11 then a quick right, now there is a bridge up ahead and if you cross the bridge you’ve gone too far and you have to turn around and go back. So we wrote a pretty good little song that went: If you cross that bridge you’ve gone too far, tell your good time friends you’ve been set free. And that takes a minute, but, it could make you a million dollars.

The problem is deciding what title is the corniest without being completely fucking corny—it’s pop music, you’ve got to be corny, but you can’t be too corny. This sort of thing happens all the time, in this case it happened to me and Ernie and Jimmy. Ernie suggested a lyric, If I said you had a beautiful body would you hold it against me? We all said, oh god that sucks so bad! Then the Bellamy Brothers made about two million dollars off of it. Don’t always throw it away just because it’s shit—I don’t know any painters that do.

Now, let’s take a look at these two bits of text:

From Hank Williams’ song “Cold, Cold Heart”

I tried so hard, my dear, to show that you’re my every dream

Yet you’re afraid each thing I do is just some evil scheme

Some memory from your lonesome past keeps us so far apart

Why can’t I free your doubtful mind and melt your cold, cold heart?

And a line from an Ed Ruscha drawing, with half the number of words:

GIRLS WITH NARCISSISTIC PERSONALITY DISORDERS

Now, both of these little phrases operate on the same principle. Both of scan, in the sense that they have a level of euphony, but what else holds them together? In the case of Hank Williams, it all holds together – Some memory from your lonesome past keeps us so far apart / Why can’t I free your doubtful mind and melt your cold, cold heart? – pretty good for a twenty-two year old kid, but what is good about it? Now the point here is that most songs are held together with structures that are not quite visible, but the Ruscha and the Hank Williams are held together by the internal “R” sound. Read the Williams, it’s got about thirty-two internal “R”s. The Ruscha is very similar. What happens when you’re writing a song is you’re trying to embed a structure that nobody notices—you know this song and you didn’t notice the “R”s. I know this song and I didn’t notice until I looked. So you’re involved in embedding structures of one sort or another and in many cases the rest of the song doesn’t even have to rhyme. It helps if it rhymes but it’s not that important. Why don’t we listen to “Once Bitten Twice Shy”—this is a straight ahead little pop song written by Ian Hunter, with Mick Ronson on the guitar.

ONCE BITTEN TWICE SHY

What you have here is the verses are all pushed—one-and-two-and-. And then when you release into the chorus you have a kind of straight eighth note beat—my, my, my, once bitten twice shy—which is pretty steady, which is what makes it feel like it’s releasing. The verses at the same time, are all pushed. They come a little sooner than you might wish if you aren’t paying attention. So you build up a structure describing Rock & Roll life on the road, building up tension and then it releases with, my, my, my, once bitten twice shy. Which I presume has some symbolic meaning. [Laughter.] My point is: this is a really simple song, but we would all go to heaven and die to have written my, my, my, once bitten twice shy. It’s got rhythm and it’s got kicks and everything that you want. And so, if you have that, you’re half-way home—Halfway home in the parking lot / By the look in her eye she was givin’ what she got. Also, and this is so often the case with Rock and Roll songs, is they’re really fun to play. They feel real good. Ian Hunter is a really good songwriter. Can we listen to the Ian Hunter song “Irene Wilde”?

IRENE WILDE

This is a nice all-truth ballad. Obviously, it’s a sentimental song, and if it wasn’t a sentimental song it wouldn’t be any good. Ian told me that he actually went back once and tried to look up Irene Wilde and she was married to a butcher and weighed about three hundred pounds, so ba-sically it was good for everybody in the end. The hook, I’m going to be somebody someday, is just a straight ahead Rock & Roll on-the-line hook. It’s all you want, a little bit of aspiration, and it’s a song nearly everybody can communicate with. This is what you’re looking for. You’re not looking for “Jezebel at Four Fifteen,” you’re looking for, I want to be somebody someday. The interesting thing about this tape, is that it always works. People always clap, they always scream. When you play that part they get off, I want to be somebody someday. The thing that I would bring to your attention here, as fledgling songwriters, is that you can’t fancy that up. Do you understand: it’s got to be straight and it’s got to be simple. And if it’s not straight and it’s not simple it’ll sound pretentious as shit. Playing it straight is harder to do.

Part of the dynamics of any pop song has to do with the gradual feeding in of the instru-mental and vocal parts. You are not singing the whole god damn song the first time you sing the first verse—you let it all feed in. As you can tell, you have an incredibly simple structure, and you want to do a really simple structure.

Remember: you can always do less. As we used to say in the band, you really have three choices: you can play the same thing everybody else is playing; you can play something different from what everybody else is playing; or you can just not play. Now, it’s really hard to remind your lead guitar player that he can just not play, but these options are always there.

GOODBYE TO LOVE

This is in my opinion one of the best songs ever written. It’s by Richard Carpenter and John Bettis. First point: the last iteration of Karen Carpenter singing “Goodbye to Love” is half-way through the song. In other words, that is the last time you hear the hook, which is in the middle of the song. Then you go into the chorus and then to the instrumental. The instrumental is played by Tony Peluso, a very good guitar player. This is a revolutionary cut in the history of American music in the sense where you play a fuzz tone driving guitar solo up against the harps and the violins. That is kind of amazing, and the reason that it works is that the guitar melody is within the range of Karen Carpenters alto. Karen has a very strong alto voice and so does Tony Peluso’s guitar, and they are in categorical harmony as you move through it.

The part I love the best, even as I love nearly everything about this song, is that it is a song that does what it says. In other words, it says goodbye to love, turns up guitar and for half the song we have said goodbye to Karen—it reenacts what it says. There are not many songs that can pull that off.

But also what happens is it is constructed oppositely from what I have been describing. I’ll say goodbye to love / No one ever cared if I should live or die/ Time and time again the chance for love has passed me by/ And all I know of love/ Is how to live without it / I just can’t seem to find it—what happens is the space between each “goodbye to love” expands rather than contracts. As we said, in most songs the spaces between one cookie and the next gets shorter and shorter as the song goes on. In this song they get longer and longer so it spreads out, and you have a very classical situation where you’re waiting on the return of the hook, like Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. I think that the virtue of the song is first that it does what it says, it does say goodbye to love and bring you out into rock and roll world where I fear

Karen wished to be the whole time while Richard was writing pop songs. But it reiterates the subject and then it dances off at the end and disappears into a riff, which is what you want to do if you play Rock & Roll. You want someone in the audience to notice that, she said goodbye to love and now she’s moved on. As a modality of designing a song this is quite good. Also, for a pop ballad it’s got some odd rock and roll aspects to it. First of all, the louder you play it the better it sounds. This doesn’t happen very much to pop songs. Feelings, nothing more than feelings—like that, usually they get softer and sweeter.

Richard always had the virtue of writing a song that was to Karen’s range. Then it frees Karen to sing as soulfully as she can and not try too hard, because Karen just talking will make you cry. Do you understand what I’m saying? Think of “On Top of the World”—you can listen to that song and the one thing you know is that Karen is not on the top of the world; in fact, the emotional punch of the piece comes from it being the opposite of what it’s saying. And you also know, first of all that she’s a drummer—she’s very good at sustaining pace at low speed. I admire that and I admire the whole arrangement of the thing. I like John Bettis’s lyric a lot because it’s just straight ahead adult. It’s not like fake and it’s not like “sugar, sugar,” it’s just the story.

I have an essay in my next book about this song. I describe being on 53rd Street between 2nd and 3rd avenues in a hoity-toity furniture store, trying to decide why I won’t spend the money on the couch, but I will spend the money on art. Then I hear, I’ll say goodbye to love, There are no tomorrows for this heart of mine, Surely time will lose these bitter memories, And I’ll find that there is someone to believe in—and I’m standing there expecting the structure to repeat. But it doesn’t repeat. So all of a sudden all the corner notes and half notes in the first break are transformed into eight notes and you just get a straight eight note sequence and then you go back to the verse again.

It’s like Leonard Meyers says: you make a statement, vary that statement, make the statement again, vary that statement again, and the more variation that happens the more interest you have. What you want is an ongoing pattern that has variations in it, but the variations themselves are part of the repetition, so you shift things as you wish to make them all fit together.

But in “Goodbye to Love” all of this elaborate structure is really to no end, it’s just so you can feel love going away—that is what you want to feel, a triumph over the realms of adolescent romantic love up into the realms of Rock & Roll. I think that it works pretty good. A lot of people don’t like this song but fuck ‘em.

JUST ONCE

This is a song written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, who are the best songwriters in the world. These are Cynthia’s lyrics: Just once…/ Can’t we find a way to finally make it right / To make the magic last for more than just one night / If we could just get to it/ I know we could break through it—just listen to the internal rhymes of this, they’re really elegant. This is also what we call a “power ballad.” One of the ways you can tell is you just listen to it and know it’s much better live, and any good singer can just kick the bottom out of a song like this.

It has an opening that is kind of like “Goodbye to Love:” I did my best but I guess my best wasn’t good enough / ‘Cause here we are back where we were before / Seems nothing ever changes, we’re back to being strangers / Wondering if we oughta stay or head on out the door—that is a pretty good first line, and if that is your first line, you know everything else is going to be ok. One of the reasons I included this here is that power ballads are not my favorite kind of song, but they are my favorite kind of song to write, because the harmonies are more complicated, and it’s just more interesting to make it go. My own predisposition is for what I would call “slow Rock and Roll.” To explain what I mean by that I’ll cite “Tumbling Dice” the Roll-ing Stones’ song, which is forty-eight beats per minute—that’s slow. One of the things you can always be sure of when you’re listening to people play it “Tumbling Dice” at more than forty-eight beats per minute, is that it sucks. To makes songs like that work you’ve got to really keep the tempo down. That speed is what we would call an adagio, which is right around forty-eight beats per minute. It opens up a whole lot of space. Verse ends, chorus begins, there is a lot of space in there for those thunderous drum picks ups. If you’re playing it too fast, it all disappears. And if you’re singing a lyric like, Can we finally find a way to make it right, it’ll sound stupid too fast. So you keep it slow.

AT THIS MOMENT

This song was written by a friend of mine called Billy Vera, who is now the head of musicology at UCLA. Back in the day, in the ‘70s and 80’s, he had a band called Billy and the Beaters, and they would play at bars like Madame Wong’s. This song has a very checkered career, in the sense that he wrote it and sent out the demos. The demos got a whole lot of plays. The record company said make an album, and then it kept getting plays, then it got to be a sort of sub theme on a tv show with Michael J Fox called Family Ties, which is where most people know it. And then Billy had enough money to go into the studio to make things the way he wanted.

Again, a fairly simple song. The close of the hook—if I could just hold you again—is a little like the hook in “Irene Wilde”—I want to be somebody someday. It has one of these kinds of hooks that is lapidary, as if it were carved on stone. But, actually, another interesting thing, it’s a simple song with two verses but the last half of the verse modulates up and finishes the song. The story of the song is pretty good: They were playing in Chicago and a friend of Billy’s had been dating this girl and she left him, and he was destroyed. He really didn’t know what to do. And out of witnessing his friend’s experience, he wrote the first two verses. Years go by, ten years, twelve years, by this time Billy is dating the same girl that caused the first two verses. Then she dumps Billy, and he knows the last verse: I’d subtract twenty years from my life / I’d fall down on my knees/ And kiss the ground that you walk on/ If I could just hold you again. With, take twenty years from my life, we have elevated the rhetorical level of the song.

That’s a major statement.

So this is the moment of this lecture in which I tell you what you should do if you’re a songwriter: You should have a little book, and whenever you think you have what could be a title for a song, write it down. Then flip over, and everything you think is a verse, enter into your little book. And if you did that for about six months, and it’s you—these are first-person state-ments—eventually you’ll look at a line from a verse, or a chorus, or a title, and the whole song will just come together, because you’ve written it in three or four little pieces. That is a pretty good way to write songs. Again, as a songwriter you’re looking for something that is eccentrically everybody. In other words, you want to be in the world of everybody; here comes every-body as James Joyce would say.

I have some live cuts of this song and people go crazy. But, again: Cliched?—yeah. Sentimental?—for sure. Bad?—no way.

One particular thing that I wanted to mention is that most pop songs have this in common with sonnets, they have what you call a volta—meaning, they turn. The minute they turn, you know you’re on your way out, of a sonnet or a song. When you get to the part, to that last verse, and it gets really intense—I’d subtract twenty years from my life / I’d fall down on my knees—that’s pretty serious, and also the extent to which it does not rhyme with everything sort of tells you that you’ve hit the groove that is going to get you out of that song. When you’re writing a song you’re always looking for the way you’re going to get out. When you know that, you’re cool.

There’s not much to the song, but it makes people cry. When you play this as your final song in a set there ain’t nobody not gunna get laid, taking standard rock and roll values. It does have that virtue. It’s a song that will go as high or as low as you want to sing it. The end of it can really open up with repetitions and riffs and things like that. A lot of what I’ve been arguing here today, is that you tell the truth. Just tell the truth. And you fix it as best as you can.