- Drumming for the Black Madonna

- Right Advice, ADVICE NOT GIVEN: A GUIDE TO GETTING OVER YOURSELF BY MARK EPSTEIN

Shirin Neshat: Fervor and Turbulent

Karen Mathews

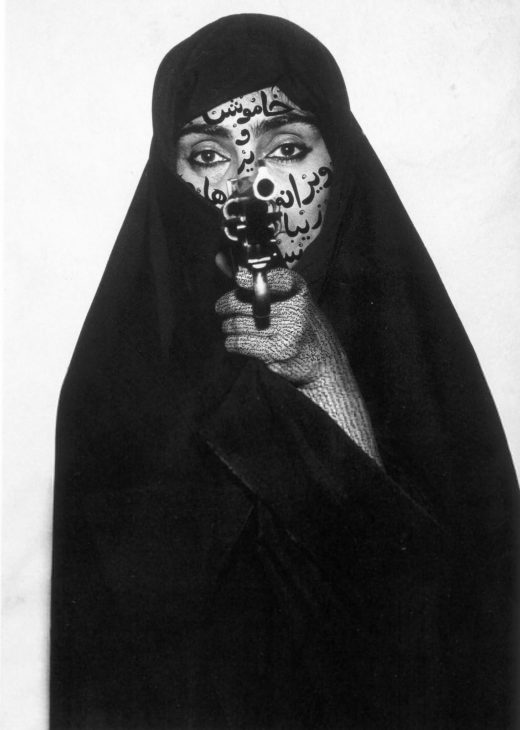

Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah, 1993-7

Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah, 1993-7

August 8 — October 22, 2017

Shirin Neshat returned to South Florida recently in the form of two dual-track films exhibited at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, and her work nicely complements the institution’s strong photography collection. The two films that comprised the exhibition, Turbulent (1997) and Fervor (2000), are classics epitomizing the talent that brought Neshat to international prominence. Some twenty years after Neshat created these works, this exhibition provides the opportunity to assess her artistic legacy, the influence she has exercised over a new generation of Iranian photographers/artists, and the potential for understanding and exhibiting contemporary Iranian art in an innovative and inclusive manner.

Turbulent is one of Neshat’s most critically acclaimed films, having been awarded the Lion d’or at the Venice Biennale in 1999. It was also her first foray into the realm of video, a medium that subsequently has played a major role in her artistic production. A consistent theme in her work has been the recognition of sharply-delineated binaries concerning gender roles in Iranian society, and she highlights these dichotomies literally in black and white without the promise of synthesis or resolution in these two films. Turbulent consists of two films displayed on opposite walls. It is impossible to watch them simultaneously so the viewer must choose where to direct his or her attention immediately upon entering the display space, taking sides in the gendered competition that consists of dueling approaches to the performance of poetry by Rumi, the Persian mystic poet. The male singer begins first, performing Rumi’s love poem in a beautiful and lyrical way to an appreciative audience in an auditorium. The female singer then begins her rendition on the opposite wall in a non-traditional vocalization that is full of passion but perhaps more dissonant. She performs, however, in an empty hall, as women are prohibited from singing in public in post-revolutionary Iran. In these simple, black and white films, then, Neshat chose not to present a narrative or tell a story. Instead she employed both visual and aural modes to convey intense emotion differentiated along gendered lines.

Fervor was the other dual-channel film on display in the exhibition, created by Neshat in 2000. In the case of these films, the two are projected side by side; the dualities explored by Neshat, then, are not expressed as much in the physical display as in the content of the films. Fervor explores gender binaries in the context of a public lecture or sermon performed by a zealous and charismatic speaker. Separated by a tall, black screen that also demarcates the boundary between the two films, male and female audiences listen to the story of Yusuf and Zulaykha presented by the speaker. Multiple versions of this tale exist, with the Qur’anic story of Yusuf (Joseph in the Bible) emphasizing his goodness, purity, and innocence in the face of female sexual aggression. Joseph struggles to protect himself as Zulaykha, the wife of the ruler who adopted him, attempts to seduce him and then accuses him of rape when he spurns her advances. In Persian literary traditions, however, Yusuf and Zulaykha’s story has a completely different ending, where they fall in love and live happily ever after, as is the case in any good fairy tale!

So, which version of the story is the speaker narrating? The story of spiritual or carnal love? A tale of transgression and punishment or love and mutual respect? That is not made clear in the film, but the speaker is successful in whipping the crowd up into a frenzy. As the excitement and fervor of the audience escalates, the male and female protagonists remain aloof, detached from the people around them, and they exchange glances though they cannot see each other through the veil that separates them. We, the omniscient viewer, can witness their connection and wonder in which direction this seemingly clandestine or forbidden relationship might lead. Later in the films the two come together, just steps away from one another in a bleak, barren landscape, but Neshat resists the temptation to provide a synthetic, redemptive moment.

Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah, 1993-7

Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah, 1993-7

It is the narrative component and the possibility of drawing multiple conclusions that I think makes Fervor so compelling, perhaps more so than Turbulent. The viewer is given the raw material of a story in the form of paired opposites—male/female, black/white, together/alone, animated/reserved, passive/aggressive—and he or she can ultimately decide how the narrative will end. Will the man and woman in the film be able to surmount the physical barriers and cultural roadblocks that divide them, or will they simply take the path of least resistance and go their separate ways?

In Turbulent and Fervor, Neshat addressed issues of gender and employed the symbol of the black veil or chador to represent the persona of women in the public sphere. This potent and multivalent symbol also took center stage in some of her best-known and influential photographic work, the Women of Allah (1993-7). This photographic series (still not shown in Iran) introduced Iranian art to a larger audience and established a visual vocabulary that continues to be explored by artists in Iran and the Middle East to the present day. Neshat’s photographs in this series consist of a potent mix of simple elements: veil, gaze, calligraphy, weaponry. Created with the intent of acknowledging the role of the women’s movement in the Iran-Iraq war and the Islamic Revolution, the militant, veiled figures in Neshat’s photographs elicit an array of responses and highlight more of her binaries or contradictions. In the photographic series, a woman (most often Neshat herself) is draped in a black chador. The parts of the body not concealed by cloth are covered in calligraphy. In their form, the words evoke Qur’anic verses and religious texts but are, in fact, contemporary Persian poetry. The women point their weapons directly at the viewer in an aggressive, threatening stance. Neshat plays here with the juxtaposition of femininity and violence. The chador, seen as a sign of female submission and passive acceptance of religious beliefs and practices, is contrasted with the militant and patriotic fervor that inspired women to engage in political discourse and violent demonstrations at key moments of their country’s history. Neshat deployed the female body as a battleground and challenged received notions about the meaning of the veil, initiating a dialogue that has been taken up by Iranian artists living inside and outside of their home country.

The use of the veil as a symbol in the artistic production of the Middle East and Iran, by male and female artists alike, has become so prevalent that it has given rise to heated debate concerning its relevance and meaning. Some artists have argued that its omnipresence has turned it into a self-parody, emptying it of its power to address significant political and social concerns. It is a facile tool particularly for artists in the diaspora whose work is aimed at a Western audience. For viewers in the west it serves as a self-perpetuating colonial fetish, revitalizing Orientalist iconography while self-exoticizing the artist. Despite these critiques, many Iranian artists still see the veil as an effective and subtle means with which to interrogate notions of identity, the interplay between tradition and modernity, and the significance of masking and concealment. These are all themes addressed in the photography of the four artists discussed here, a group that incorporates both male and female photographers, those living and working in Iran and others who form part of the large Iranian community in the diaspora.

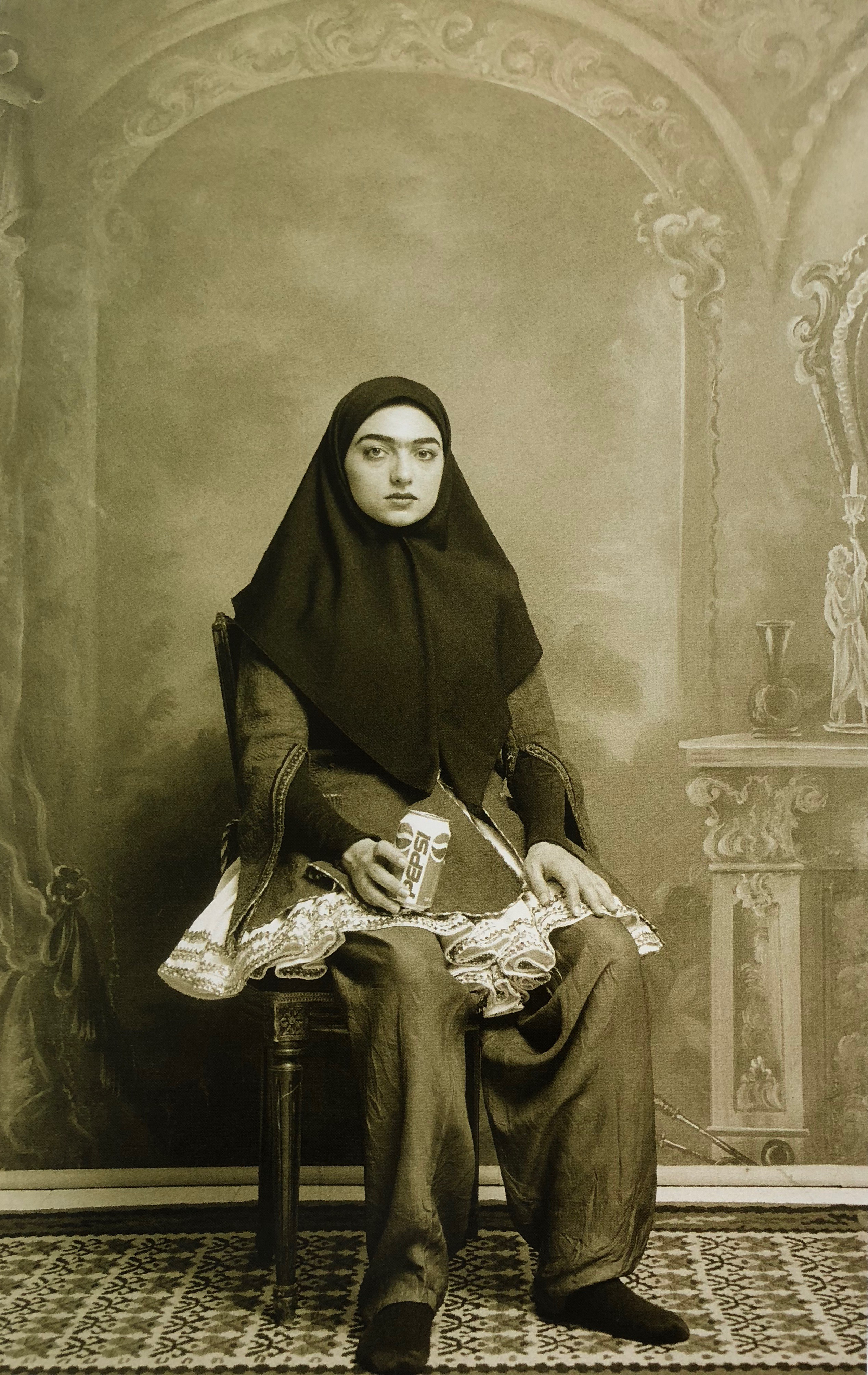

Shadi Ghadirian is a photographer based in Tehran and created her Qajar series (1998) soon after Neshat’s Women of Allah was exhibited. The set of photographs consists of staged, studio portraits of contemporary Iranian women in clothing from the Qajar period, a modern dynasty ruling from 1785-1925 that was known for its openness to the west, but one that is also credited for enabling the Western exploitation of Iran’s natural resources, particularly its oil. In the Qajar period women enjoyed a high level of freedom and their dress reflected western styles, fashions that were far more revealing than what Iranian women wear in public today. Arranged before theatrical backdrops in the stiff, artificial poses and sepia tones of Qajar photography, modern women address the camera directly while holding contemporary commodities—radios, cans of Pepsi, vacuum cleaners, and bicycles. The consumer props contrast with the antiquated clothing of the women, but the goods on display were all chosen because they are items banned in Iran, symbols of western capitalist culture and the immoral and lascivious lifestyle it fosters. Ghadirian orchestrates an encounter across time, a dialogue between the past and present, questioning whether women in Iran are actually better off today than they were at the turn of the twentieth century even with all the conveniences of modern technology. She also blurs the lines between reality and fantasy, inviting viewers into this hybrid construction to get a glimpse of the past only to be confronted with symbols of their own contemporary consumer culture.

Shadi Ghadirian, Qajar series, 1998

Shadi Ghadirian, Qajar series, 1998

Shirin Aliabadi, Miss Hybrid, 2008

Shirin Aliabadi, Miss Hybrid, 2008

Shirin Aliabadi also investigates the intersection of the veil and pop culture in her photographic series Miss Hybrid (2008), presenting a more lighthearted but still pointed critique of social norms in contemporary Iran. Her images consist of bust length portraits of young Iranian women decked out in the latest fashion accessories favored by the country’s elite. The women wear blond wigs and blue contact lenses as they gaze coquettishly at the camera. Some eat lollipops or popsicles, others pose with motorcycles and expensive headphones or talk on their cell phones. Like the costumed figures in Ghadirian’s Qajar photographs, these young women adorn and surround themselves with props, tools and symbols of Western culture. But Aliabadi’s posed models, with their designer scarves, sunglasses, and hair clips, wearing bandages across their noses alluding to recent plastic surgery (Iranians claim that their country is the nose job capital of the world), take this slavish emulation of the West even further; these women spare no expense to conform to Western standards of beauty.

Their bright clothes, frivolous accessories, and sexually-charged poses might appear comical, even farcical, as the women become caricatures of themselves. But their seemingly trivial fashion statements also serve as a provocation, a form of “lipstick jihad,” as Iranian women resist the stringent controls on their public appearance and embrace Western styles in opposition to the Iranian government’s official stance on the nefarious influence of the West. These women sport examples of “bad hijab”—headscarves that expose too much hair or are too bright and flashy. They wear excessive makeup and have facial piercings, transforming their bodies in a challenge to the state-sponsored guidance patrols that enforce standards of public modesty for women. The adoption and rejection of Western culture have always moved in cycles in Iran, with a long pedigree dating back to the seventeenth century. In the twentieth century it was the “Westoxification” or “Occidentosis,” the slavish and unthinking adoption of anything western, that characterized the regime of the last shah and fostered popular support for the Iranian Revolution1. Now, a generation after the revolution, women’s bodies draped with luxury goods from the West become sites of resistance, and the aggressive alteration and excessive ornamentation of the female body (particularly the face as it is the only part of the body visible when wearing the chador) provide a public stage where Hermès scarves and Chanel sunglasses can be symbols of social opposition and rebellion against religious authority.

What began as a game—a headscarf dangerously askew, a flash of red lipstick, the downloading of an app to avoid morality police checkpoints— has become far more serious as women have taken to the streets of Iran’s major cities to protest the compulsory wearing of the veil or chador in public. Over the years, millions of Iranian women have been warned, arrested, or sent to court because of bad hijab, and the anti-government demonstrations that have rocked Iran over the past few months have provided the platform for orchestrating opposition to the veil. In late December, a lone woman stood on a box on Revolution Street in Tehran, removed her veil to expose her hair and tied the headscarf to a stick as a symbol of protest, giving rise to “White Wednesdays” where the standard black chador is replaced with a white veil that is taken off and waved as if it were a flag. So far 29 women have been arrested for such acts of civil disobedience, behavior that political officials have blamed on outside influences and radical Iranians in exile. The female protesters insist that this is an internal, grassroots movement, one that is gaining considerable momentum through social media. Whether an individual woman chooses to wear a veil or not, the protests in Iran have empowered women to assert their right, not that of the government, to determine the degree to which they reveal or conceal their bodies in the public sphere.

Abbas Kowsari, Women Police Academy, 2006

Abbas Kowsari, Women Police Academy, 2006

Male artists, too, employ the veil as a visual tool in their artistic production, as seen in the photography of Abbas Kowsari and Majeed Beenteha. Kowsari began his photographic career as a photojournalist, but the quality of his work and the particularly propitious environment for the visual arts in Iran at this moment have allowed him to pursue a full-time career as an artist. His recent work has become a bit more aestheticized and constructed, but an earlier series of photographs, Women Police Academy (2006), still retains the feeling of reportage. In 2005, Kowsari was invited to photograph the graduation ceremony of the first group of female cadets from Iran’s Police Academy. Under an innovative program initiated by Tehran’s police chief, women received intensive training to form all-female police units. The graduation ceremony provided the opportunity for the cadets to display the skills they had honed, and Kowsari documented the women practicing martial arts, performing high speed car chases, and scaling the Police Academy walls, all in full chador. Kowsari’s photograph of the women climbing up the building on ropes documents an event, but proves that real life can be even more fantastical than an artistic construction, turning reality into illusion.2 The image has a decidedly surreal quality as the women exert themselves physically to scale the wall, but the flowing and fluttering of the chadors in the wind belies their extraordinary effort and dematerializes their bodies, making them resemble trembling leaves on a vine, or moth-like creatures moving towards a beckoning light. The chador here masks and conceals, but it does not diminish the strength, confidence, and determination of these female law enforcement officers as they succeed and excel despite the physical and conceptual encumbrances placed upon them.

Majeed Beenteha uses the symbol of the veil to highlight the contrast between concealment and exposure of the female body while exploring the potential of the chador as a political symbol, as he juxtaposes the standard outer garment of the Iranian female with the Iranian flag. His series National Riddle (2010) employs a female with a white head scarf as the central figure, displaying her in a series of poses. Her upper torso is covered with the scarf, her hands concealed in black gloves, and eyes covered with chic sunglasses; she is the picture of Iranian female modesty from the waist up. From the waist down, however, she is completely naked and the battle between the concealing and revealing of a woman’s body is played out on this female figure. But this is not a private spectacle but a public, national one, as the half-clothed female is displayed on an Iranian flag that forms the background of a postage stamp. Women, their bodies and their role in public culture are pushed into the spotlight, and Beenteha comments on the often inconsistent and even contradictory attitudes towards the presence of women in the public sphere and their participation in national politics in his visual juxtaposition of two opposing states of dress for contemporary Iranian women.

All the artists addressed here use contemporary Iranian society and the role of women in it as a touchstone for their artistic production. Such focus on the unique political situation in Iran begs the question of whether all Iranian art must be about Iran. The obvious answer to that question is no, and there are many artists from Iran who resist being stereotyped or pigeonholed based on their country of origin, and conduct explorations of form, technique, and subject matter devoid of national political commentary. But, in contrast to this group that aims to transcend Iranian identity, there is a quite substantial number of visual artists from Iran who choose to devote their artistic energies towards addressing aspects of existence within their home country. There are several reasons why Iranian artists might have such a laser-like focus on national issues, informed by the tension between tradition and modernity being played out in present-day Iran. On the side of tradition, Persian culture (a far larger cultural category than the contemporary state of Iran itself) has flourished for millennia and the visual and literary traditions of Persia are a great source of pride for modern Iranians. In the medieval and early modern period, Persia was a flourishing cultural center, the envy of its neighbors for its prowess in poetry, painting, textiles, and ceramic production. The recreation and restoration of this extraordinarily high level of creativity and dedication to aesthetic pursuits continues to be an important component of contemporary artistic production as an ongoing dialogue is staged between Persians past and present.

The uniqueness of Iran on the contemporary world stage can also explain the interest in using the country as a rich source of artistic subject matter. Iran has undergone drastic change over the past thirty years, and its tumultuous history inspired a generation of photographers who sought to document the transformation of a nation. Iran defies easy categorization, as it is often included under the rubric of the Middle East, but it is not a Middle Eastern country, consisting of a population defined by the Persian language and Persian heritage rather than Arab culture. The Iranians are Shi’ite Muslims in a predominantly Sunni world, a distinction created purposely in the sixteenth century to differentiate the Persian-based Safavid Empire from its Muslim neighbors. Iran sits in a highly strategic location, at the crossroads between east and west and open to influences from multiple cultures. It is a fascinating but volatile place, perhaps even more off limits than before to an American audience given recent United States policy decisions like the de-certification of the Iran nuclear deal. In the artworks created by Iranian artists, however, we perceive and appreciate their efforts to come to terms with their country’s storied history and complex contemporary identity. It will be a pleasure to see the future work of this vibrant community of talented and engaged photographers as they continue to critique, question, and potentially reform Iranian society through the force of their photographic work.

1 Occidentosis: A Plague from the West is the title of an influential book by Jalal Al-i Ahmad (first published in the 1960s and translated into English in 1984) that critiqued the corrupting influence of western culture on Iranian society.

2 Abbas Daneshvari, Amazingly Original: Contemporary Iranian Art at Crossroads (Costa Mesa, 2014), p. 292.

FURTHER READING

Chiu, Melissa, and Melissa Ho. Shirin Neshat: Facing History. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2015.

Daftari, Fereshteh. Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2017.

Daneshvari, Abbas. Amazingly Original: Contemporary Iranian Art at Crossroads. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 2014.

Daneshvari, Abbas, ed. Contemporary Iranian Photography: Five Perspectives. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 2017.

Eigner, Saeb. Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran. London: Merrell, 2015.

Gresh, Kristen. She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World. Boston: MFA Publications, 2013.

Grigor, Talinn. Contemporary Iranian Art: From the Street to the Studio. London: Reaktion Books, 2014.

Issa, Rose, ed. Iranian Photography Now. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2008.

Issa, Rose, ed. Shadi Ghadirian: Iranian Photographer. London: Saqi, 2008.