The Visitor’s Gaze: Cristina García and Here in Berlin

Chantel Acevedo

1.

Of the many stories one finds in Cristina García’s latest novel, Here in Berlin (Counterpoint, 2017), my favorite is the one told by Ernesto Cuadras, the young Cuban man who spends five months as a prisoner of war on a German U-boat. In the story, Ernesto is captured during his shift as a night watchman. The German who accosts him asks for supplies and rum. When Ernesto denies having anything to give, he’s taken into the belly of the submarine. There, he spends several months learning German, becoming friendly with the other young men, battling a British warship, and ultimately, is released back to Cuba, where nobody believes Ernesto’s story. He spends the rest of his life scanning the horizon from his veranda, binoculars at the ready, waiting for a German submarine to take him away once more.

Its last scene is an echo to another moment from a different García novel—her celebrated debut, Dreaming in Cuban, of course. In that novel, we see Celia del Pino, the book’s protagonist, on a veranda of her own, also looking out to sea, “in her wicker swing guarding the north coast of Cuba.” It’s been 26 years between García’s debut and the release of Here in Berlin. One can’t help but think of these scenes as bookends of sorts. El cubano y la cubana looking to the sea, she, wary of an invasion she’s been readying for her whole life, while he is eager for its arrival.

These two opposites seem to me to sit on either end of the vast spectrum of characters that García has given us over the course of her long career. Her characters often call Cuba home, but their gaze extends elsewhere. From Chinese-Cuban in Monkey Hunting, to Central America in The Lady Matador’s Hotel, to a Swiss boarding school in her only Young Adult novel, Dreams of Significant Girls, García’s work is global, as seen through a Cuban pair of binoculars.

The unnamed Visitor in Here in Berlin, the person whose gaze we inhabit, is a Cuban woman running from certain difficulties – a failed marriage, a challenging relationship with her mother, and an empty nest. She comes to Germany seeking Cuban stories (and why wouldn’t she? Los cubanos, Cubans like to say, estamos metidos en todo). The narratives she collects make up the novel, and we follow the Visitor along, like the Cuban shadows she never fully escapes.

2.

To say that Dreaming in Cuban was a formative novel for me to have read at a particular time in my life is an understatement. This is a story I have told many times when asked about my own path as a writer.

The short version is that I was still in college, writing boring stories for my creative writing courses about families I thought were of “literary value.” This is to say, I was writing about white people of Irish descent, who lived in upstate New York, and talked about the Great War. I was nineteen, and well-read only in what was considered the canon. My stories earned A-minuses and B-pluses, but they were dead things, full of dead people. One day, at the Westland Mall in Hialeah, I wandered into a Walden Books, or a B. Dalton Books (I can’t remember which. We had an embarrassment of mall bookstore riches back then), and saw the cover of Dreaming in Cuban, with that sleepy-eyed, cigar-box woman on it, the red hibiscus tucked into her hair. She looked like my grandmother’s engagement photo.

My first thought was: “Is this allowed? A story about Cubans written in English?”

My second thought was: “How much money do I have in my wallet?”

The novel changed everything for me.

It wasn’t only that García had written a story about three Cuban women and their dreams of Cuba and for themselves, but that these women were each so vastly different politically. Was this allowed, too? I marveled at this book, which treated Cuba in so many complex and wonderful dimensions.

It was as if I were reading in 3-D for the first time.

Suddenly, the stories that my grandmother had told me all of my life took on a different meaning. Where once I thought of them as old-fashioned and impossible, I now saw patterns of feeling, of the way immigration and exile had shaped her life, my mother’s life, and my life. In the gaps of her many narratives, I found myself inventing, supplying a fiction that felt essentially true.

3.

There’s a marvelous moment in Alice in Wonderland where Alice is given advice on how to tell a story. “Begin at the beginning,” the King says, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.” It’s advice that, over the course of her writing career, García has found creative ways around. Here in Berlin is made up of monologues, each by a different person. The novel is a tapestry of stories, a museum’s worth of stories, of witness bearers, men and women who have lived through a particular moment in history, and have come out on the other side with a mouth full of narrative.

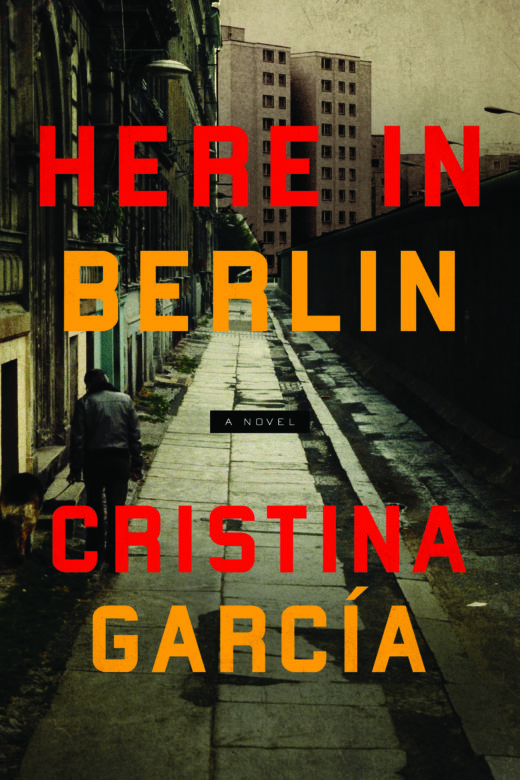

Cristina García

Cristina García

The second story in Here in Berlin is that of Sophie Echt, a Jewish woman whose husband hides her in a tomb in order to save her from the Nazis. Encased in that dark, fetid place, Sophie panics at first, and then begins to memorize poetry, befriends a snake, and finally, after her escape, forgives her husband’s adultery: “It was the least I could do for saving our lives.” It’s a shocking story with echoes of Poe, grounded ultimately in an act of self-sacrifice.

In another story, an East German official is tasked with creating a pop culture moment—a dance craze for the Soviet youth. He creates the ITSATSI! inspired by, who else, a diplomat from Havana called Tania Tania, who advises he watch her dance until “you can suck the marrow from my bones.” The ITSATSI!, its name a rearranged version of Stasi, is a failure, but for the official, it represents a highlight of his life.

García gives us a complicated Berlin, where the past is not quite past. An Angolan opthamologist, an Eva Braun look-alike, and a Cuban historian are just some of the other characters that bring Berlin’s history to life. “The upheavals of history,” says Dr. Molina, the historian, “create the most improbable of human consequences.” There is, indeed, a touch of improbability among them, and a dark humor that runs parallel to the tragedies and losses the characters describe to the Visitor.

These are not happy stories, and indeed, the Visitor herself is unhappy. A failed marriage, an abusive mother, and an empty nest have contributed to her own sense of displacement. The Visitor is not literally on a veranda, binoculars in place, looking out, but she is spiritually so. The stories she seeks in Berlin are sad, but sustaining. In each case, the characters can look back on these difficult moments in their lives and label them as transitory. There is life beyond the war, life beyond the wall, they seem to be saying. Their stories are behind them, but they are worth retelling. The Visitor is attracted to this post-story life, wishing to spend her days with a butterfly net, “trapping flying bits of color here and there.”

4.

I wasn’t conscious of having done it until after it was done. My fourth novel, The Distant Marvels, opens with an elderly woman in Cuba, scanning the horizon as a hurricane whips its way towards the island. It was only after the novel was published, and I was reading it aloud on book tour, that I realized I had created my own version of Celia del Pino. What is it about this nearly atavistic, seaside image, this gesture of gazing and longing?

For Cuban-Americans, particularly those living in Miami, the answer stares us in the face. Cuba, near yet so far, remains largely forbidden, though the “Yo no voy” bumper stickers of the 80s, once pervasive, are now gone. The idea of exile (not just immigration, but exile) was once palpable in Miami, the politics about it all far more volatile than they are now. Massive waves of highly politicized Cuban immigration totally shaped the Cuban-American experience. Pedro Pan, the 60s airlifts, Mariel in the 80s, and later, the Balsero Crisis of the 90s, weren’t just about the influx of Cubans to Miami. They were about the separation of families, about ideologies that had been hardened in a crucible of feeling, and political games of chess between los de aqui, y los de allá.

Today, the whiplash that happened between Obama’s visit to Cuba, opening up relations, and Donald Trump’s election, are still being felt. In a sense, much of Cuban Miami is still gazing out at the sea, eyes to the horizon, scanning for something lost. Interestingly, the Angolan opthamologist and her cataract-burdened patients come up again and again in Here in Berlin. They long to see, but time has complicated the matter for them. One, a nurse who did unspeakable things during the war, complains of a dark hole in the center of her vision. “The world is vanishing around me,” she says. That first generation of Cuban exiles post-Revolution, now in their eighties and nineties, might say the same thing.

5.

Cristina García is the founder and director of a writing workshop she calls Las Dos Brujas. Several years ago, I joined Las Dos Brujas for a week in Miami. The group met in a church on Key Biscayne. Each morning, Cristina would arrive with pastries and coffee. We would gather in a room paneled in wood, around a large table. Mostly emerging writers, and almost all female, the attendees listened as García spoke about a method she calls “Cultivating Chaos.”

Her theory was that writing happens in the tensions between unlike things, in much the same way that metaphor and simile work. And so, someone like me, for example, halfway through a manuscript, might benefit from reading a few new poems, and forcing myself to use random words from the poem in a new sentence. Who knows what the new associations might trigger? We wrote down anonymous secrets on slips of paper and wrote from there. We looked at images of strangers, and wrote some more. Indeed, there really was something chaotic about it, but in the very best way. “Open a gill into your work,” she would say, a phrase I’ve used with my own students since. Into that gill I poured poetry and descriptions of photographs and the secrets of strangers. What emerged was a kind of writing I didn’t know I was capable of.

In the afternoons, García met with each of the attendees to discuss their manuscripts. When it was my turn, I treated her to a late lunch instead. We talked about my work and hers, about growing up in a Cuban home, about her Zumba practice. She mentioned going to Berlin in the future, but said nothing about writing there, or telling a story set in Germany.

I might imagine her in Berlin, like the Visitor, but not exactly so, gathering scraps from the people she met. A name here. A song lyric there. The chaos of a rainy day and a slick street. An old woman with cataracts. It’s all invention on my part, of course, but Las Dos Brujas offered not only a peek at García’s writing practice, but a way forward, too.

6.

Here in Berlin was published in October of 2017, two months after the infamous Charlottesville rally, in which white supremacists and Neo-Nazis shouted “Blood and soil,” a Nazi slogan, in response to the attempted removal of a Confederate statue. For most of us watching the news, the footage seemed unreal. If 2017 revealed anything, it was that the Nazi ghosts of World War II still haunted the world, and that for some, they still held their appeal.

Here in Berlin is unflinching in its gaze, introducing us to characters with pasts that might otherwise be buried. One reads Here in Berlin and suddenly, Charlottesville does not seem so unreal after all. How long ago was World War II, really? In the grand scheme of things, not very long at all. Recriminations, regret, and rationalizations pepper the stories. These old Berliners (and most of them are old, or at least, old enough to have something to say about post-war Berlin) speak to the Visitor without censorship. The revelations are surprising and often shocking. Though the past was long ago for them, it is also very much shaping them still. The technique of it—of having these characters speak so openly to the Visitor—is so skillfully done that each story feels like part of a bigger novel, as if we might follow each character into the pages of his or her own book.

Though not considered a historical novelist, generally speaking, García’s work often finds itself playing in the sandbox of history, seeking shapes and patterns in the swirls of it. Here in Berlin, I would argue, could be the most important book of 2017, a year that asked so many questions. The answers, we find, are sometimes behind us.

7

Twenty-six years ago, Cristina García was the first Cuban-American woman to publish a novel in English. Only twenty-six years. It seems not so long ago to me, now that I’m in my forties. I think of the writers who followed shortly thereafter—Ana Menéndez, Achy Obejas, Ruth Behar, and so many others, the list growing every year, it seems, with second and third generation Cuban-Americans. For so many of them, Dreaming in Cuban was the keystone work, the first brick in the path. For me it was a Rosetta Stone, a decoder of fiction, a permission slip to tell my grandmother’s stories, an open gate.

Literary fiction today seems a little more inclusive, a little more diverse. Yet there is still quite a way to go. Writers of color and those who write from the margins might still find themselves “tokenized” on college syllabi, or discriminated against by editors who haven’t figured out that our stories sell, they really do, and that our people read, too. But arguably, the field, though far from level, is more balanced than it’s ever been.

“Is this allowed?” I asked myself when I first read Dreaming in Cuban, as if there were some rule against Cuban-Americans writing about Fidel, and orishas, and the Bay of Pigs. What did I know? I was, perhaps, a poster child for the #RepresentationMatters campaigns on social media.

Back in 1992, Michiko Kakutani described García’s first novel this way: “It announces the debut of a writer, blessed with a poet’s ear for language, a historian’s fascination with the past and a musician’s intuitive understanding of the ebb and flow of emotion.” This description would be just as apt today for Here in Berlin. It strikes me just now that the Visitor has been present in all of García’s novels, asking just the right questions of the characters so that they may lead us to rich revelations and transcendent confessions. She has taken us out of Cuba and back again. Her characters look out to sea, or gaze into the eyes of the Visitor, and ask us why we still care, why Cuba still matters, why language matters, why anything does. And at the end of the book, we emerge blinking and astounded, having been somewhere new and asking, like the Visitor does, “Do people remember only what they can endure, or distort memories until they can endure them?”

There isn’t an answer to that, of course. But like the Visitor, who “had listened to others’ histories [and] was finally released from her own,” we can’t help but think of our own stories and how we might tell them to someone eager to listen, too.

Chantel Acevedo is the author of five novels, including The Distant Marvels and The Living Infinite, published by Europa Editions. She is an Associate Professor in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Miami.