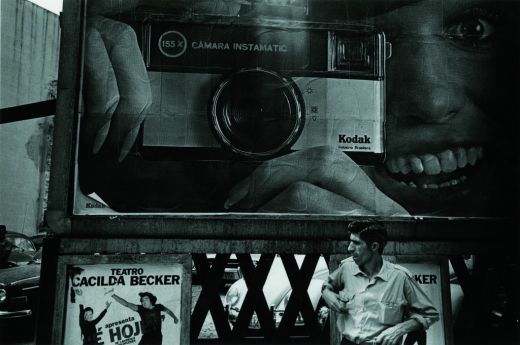

Paolo Gasparini, Caracas and its Architecture (Caracas y su arquitectura), 1967-68. Collection Leticia and Stanislas Poniatowski.

International Center of Photography

May 16 – September 7, 2014

Urbes Mutantes: Latin American Photography 1944-2013 announces itself first as an exhibition of street photography. The mobility of the photograph, the viewer is told, lends itself synchronically to the rhythms and transient excesses that compose the chaos of city life. This evocative intimacy between photography and the frenetic charge of the urban strike a particular resonance in Latin American cities. Such is the curatorial premise of the exhibition, organized by Alexis Fabry, curator of the Poniatowski collection; and María Wills, a curator at the Museo de Arte del Banco de la República in Bogotá; currently presented at the International Center of Photography in New York. Consisting of more than 300 images selected from the private collection of Stanislas and Leticia Poniatowski, Urbes Mutantes offers an incredible survey of photography across 10 Latin American countries.

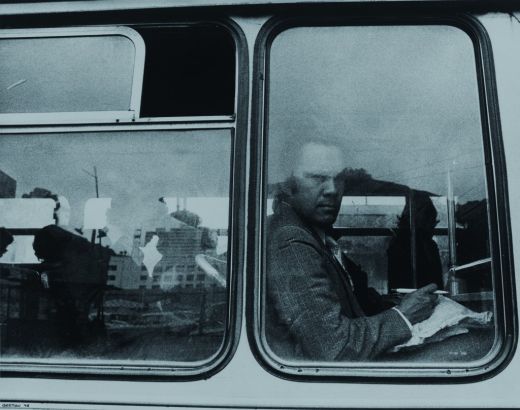

Including Argentina, Bolivia, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela, Urbes Mutantes particularly emphasizes the 1950s to the 1970s. Picturing conflict, tragedy, and grief, photographs of remarkable beauty, tenderness, and poetry also make an appearance. The blend of these elements, which in some cases seems difficult to reconcile, poses an ideological puzzle within each frame. Organized into nine thematic sections, the exhibition’s content covers, for example, “Night Life” (“La Noche en Vida”), “Pop Street Culture” (“Popular Callejero”), “The Forgotten Ones” (“Los Olvidados”), and movement—here dubbed “Displacements,” or “Desplazamientos”—by car, train, and bicycle.

Paolo Gasparini, This Sky We See Here (Acá este cielo que vemos), São Paolo, 1972. Collection Leticia and Stanislas Poniatowski.

Among the more provocative sections is “Muros Vivos” (“Living Walls”), which opens the show. Making

reference to, and building off of the political-aesthetic tradition of Muralism, these images suggest an

animistic view of urban surroundings. Walls here are surfaces for political slogans and advertising posters, but also entities unto themselves, existing figuratively as living bodies, as synecdoches of the larger public.From Enrique Metinides’s (popularly known as the Mexican Weegee) portrait of a busted brick wall with onlookers from 1962 to María Cecilia Piazza’s 1978 view of a delapidated partition in Peru, fragments and gaping holes characterize the walls on view. A conjunction of vulnerability and violence emanate from images such as Fernell Franco’s early-’90s triptych, close-ups of rough, waste strewn surfaces, sites of demolitions around Cali, Colombia. Graciela Iturbide’s concrete enclosures covered in splattered chicken blood, entitled “Pollos” (1979), similarly capture a poignant sense of disarray and upheaval.

Formally these are beautifully rendered and curious. However, once put into conversation with Maya Goded’s “Desaparecidas” (2005), notably one of the rare color photographs included in the exhibition as a whole, these photographs take on a much more ominous and ethically interrogatory position. In Goded’s image, a wall featuring a painting of the revolutionary Pancho Villa is focal, yet one becomes immediately distracted by the pool of blood in the foreground. Goded’s stain calls attention to the disappeared, murdered women of Juarez, and by extension the too-frequent impunity of patriarchal brutality. This oscillation between aesthetics and civil unrest runs throughout Urbes Mutantes.

Gertjan Bartelsman, From the series The Passengers (De la serie Los pasajeros), Colombia, 1978. Collection Leticia and Stanislas Poniatowski.

Perhaps more than any other aspect of the exhibition, the formalism of “Geometrias Citadinas,” or “Urban Geometries,” is not only striking, but moreover a persuasive justification of the show’s title. The hybrid identity of the various metropolises pictured underscores the confluence of modern architecture with colonial vestiges and baroque ambitions across Latin America. Ranging from the clearly objective composition of Armando Salas Portugal’s skyscrapers or José Yalenti’s dizzying staircases, urban centers of Mexico City, São Paulo, and Bogotá, seem to lose their specificity. Individual histories of nations and cultures begin to blur in this extensive exhibition. The works become progressively abstract as they zoom in on details of the skyline or of an individual windowpane, as in the work of Geraldo de Barros or the aerial views of Saúl Orduz. Indeed, there is a sense of a mutation occurring across images. The absence of human figures from so many of these images is troubling on second glance, however. The spaces pictured do not seem inhabitable. The futurism of a number of these metropolitan surfaces is at once seductive in form and yet disheartening in their reticence.

After passing through photographs of mass movements, street demonstrations, and the violence and upheaval that often accompany them, the finale of the exhibition brings us to the section labeled “Identidades,” or “Identities.” It is here that we are privileged foremost with returned gazes and posed portraits. And yet, there is nevertheless a lack of rapport. Somewhat ironically, the most peaceful image may in fact be Alberto Korda’s “El Quijote de la Farola,” in which a man is languidly smoking a cigarette, while impossibly perched atop a lamppost; an endless sea of revolutionaries crowds the ground around him. It is Cuba 1959, on the eve of Fidel Castro’s installation of himself as leader of the socialist state. The contemplative nature of the image, the seeming inevitability of the revolution, indeed possesses a transformative solemnity. Urbes Mutantes offers awe-inspiring variations and chronicles the flux of urban Latin America. Amidst many images of chaos and confusion, the bizarre contradiction of Korda’s work is emblematic of the most compelling inclusions.