Cristina García Rodero, a Magnum photographer and winner of the W. Eugene Smith Prize in 1989, is one of the great photojournalists—an artist/explorer who uses the camera’s democratic potential to reveal the hidden workings of the world, or to cast the visible in a new light. She has long been concerned with ritual, that physical manifestation of belief, and has such documented many facets of contemporary spirituality, be it a body of work about Spanish cults, or one about Burning Man.

Into the Rainbow Vein, the debut solo exhibition of Magnus Sodamin, features a series of paintings monumental and psychedelic. Reaching up to 15 feet in height, they appear on the barren floating walls of Primary Project’s new space like totems from a gigantic pipedream. The bright and varied palette that Sodamin brings to these compositions—acrylic mainly, and house paint—ramrods the eye, creating a retinal buzz that seeps into the inner ear. An impressive debut, but with paintings this big, how could it not be?

Here, Guillaume Désanges, who was PAMM’s first Researcher-in-Residence, teamed up with the Barcelona-based Dora García to create a temporary curatorial experiment, “an exhibition, or a diagram for an exhibition, something between the actual show, its catalogue, and its working notes.” At least that’s how the wall text has it.

A few nights before opening night, Alan Gutierrez took me to Locust Projects storage room to mix up a batch of his newly invented Locustinis. The drink depends on LP’s drink sponsors at the time. On that cool January evening, it was a creamy brown swamp of Vita Coco coconut water, Tito’s vodka, and iced tea.

When you visit Bogotá, they tell you to go to the Gold Museum. They tell you to go to the Botero Museum, which is around the corner and shares a courtyard with the Museo del Banco de la República. They tell you to take the funicular up to the church on Monserrate, but you mustn’t move too quickly, because the city itself is 8,661 feet above sea level; in the mountains it’s over 10,000. Yes, many suffer from altitude sickness, which shares its symptoms with the flu, carbon monoxide poisoning, or hangover. While you’re here, you need to drink aguardiente, you need to eat chicharrón, have you visited the Gold Museum? Oh, and don’t get into a cab, or you’ll be kidnapped.

In this intimate exhibition of California-based Catherine Czacki and April Street, sculptures and wall-hangings are connected by their common link to the human body, albeit not in a literal sense. In each, the body is an inferred presence and deferred absence. The artists highlight how things are never simply objects, which leads the viewers/lives to begin an analysis of the place of objects in their own life.

Manuela Moscoso is an independent curator living in Rio de Janeiro. Together with Sarah Demeuse she runs the curatorial office Rivet. Here, The Miami Rail asked SculptureCenter Curator Ruba Katrib to speak to her about conditions surrounding curating in South America.

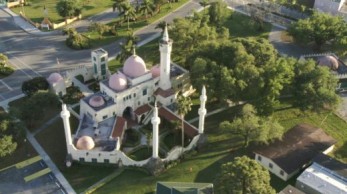

Ali Baba Avenue crisscrosses Sinbad Avenue around the corner from Aladdin and Sesame Streets. Marketers shortened the Seminole name of the area, Opa-tisha-wocka-locka, to an appellation heard as vaguely eastern sounding to those buying and selling exotic make-believe. Similarly concerned that prospects crossing Scheherazade Street might stumble over too many letters, they convinced Curtiss to name it Sharazad Blvd.

Tracey Emin’s career and life are inextricably conjoined. Her installations, sculptures, drawings and notorious neons from the last two decades are unmediated, honest accounts of her own life. Writing, in many forms, is central to her work and often appears as her own handwriting, the immediacy of which is captured and made permanent in her neons. These are the focus of her solo exhibition Angel Without You (December 4,2013 – March 9, 2014) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami.

The Miami Rail asked artist and frequent contributor Nicolas Lobo to speak to McKenzie Wark. He teaches at the New School and has published several books including Gamer Theory, The Beach Beneath the Street and most recently, The Spectacle of Disintegration. Here, they discuss the military, technology, and videogames.

In his solo exhibition Rococo Chanel, on view at the aptly titled gallery Guccivuitton, Loriel Beltran examines the visual language of taste and luxury. The show features a series of paintings that directly engage with the photographs one finds littered in the pages of fashion magazines. Beltran appropriates images from highly sexual advertisements and fashion shoots and presents them in a jumble of tan body parts.

Miami sits near the southern tip of the Floridian peninsula, a city built atop a slab of limestone after water was rerouted and cleared from the Everglades, largely over the course of the last century. Residents have braved growing pains, real-estate busts, a political exile, and crime waves of Cocaine Cowboys lore. But apart from hurricanes, which haven’t been on the area’s radar much since Katrina, Rita and Wilma left parts of the city resembling a bar-side Jenga game in late 2005, the only attention local government pays to climate is the amount of sunny days a year it can market to tourists.

On the occasion of Ai Weiwei: According to What? at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (December 4, 2013 – March 16, 2014), the artist sat down in his Beijing studio with Patrick Rhine of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in November 2013. They spoke about the exhibition, immaturity and nihilism, and China’s current sociopolitical climate.

in the bolted dusk of imagination, this bridge uncurls its busted

lugs & screws in a fishhook shape—just like the keys on the last

saxophone Sonny Rollins stashed up here for his bridge practices.

Those keys—a hexagon for rust’s trail of exhaust pipes & slowfooted

battleships. Always, oxidation over a convoy of striped

bass & trash barges built up with old stoves, empty canteens,

& tire shavings—a heap taller than the barge pilots themselves.

As you enter the gallery you encounter the name of the exhibition, Chlorophyll Bluess, painted directly on the wall in neon pink and blue. You create a narrative around this seemingly sudden inner impulse to paint, imagining the artist up on a ladder or on a chair with a can of spray paint and the lace placemat she used for a stencil. This is the same type of sequence of actions that is pictured when you look at assemblage art. A narrative is formulated around the artist building the object.

It is potential energy, buzzing with doubt and hope, that describes the imagery of End Game Aesthetics, the new solo exhibition from Aramis Gutierrez. But while he maintains a comfortable distance from many of the historical events which inspired his works, he allows for painting itself to steer its viewer towards a reincarnation of the energies prior to, during, and directly following a ballet dance. These paintings convey a desire to move politically difficult and historically messy events to the forefront; the artist’s hand is still moved by the romance of dance, but it is not without the gravity of how the world of dance operates: commanded by borders, contracts, rivalries, and state secrets.

As Far As I Could Get is John Divola’s long overdue, first museum survey. With an unusual twist, the presentation splits four decades of Divola’s practice across three Southern California institutions. The show runs concurrently at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA), Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and Pomona College Museum of Art.

Approaching from a distance, Nathlie Provosty’s “Doubleu (Dark)” (2013)’s first surprise is the discovery, upon getting near enough, that pictorial space in the work is not as resolutely flat as it initially appears, despite the apparent reductivism of her monochromatic palette. The painting’s central heraldic “U” form pushes forward with a slight pulsation, especially depending on the quality of the light that illuminates it, while the painted field as a whole seems to rotate slightly to the left and right depending on where one is standing.

Even those not haunted by dystopian technological nightmares may well have experienced the commonplace urge to both embrace and reject new technologies, and this exhibition encourages us to examine our relationship with technology by addressing both our enthusiasm for new advances and fears that technology will replace us.

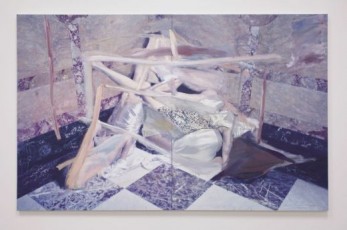

It was a simple performance by the troupe [ce n’est pas nous]. As composer Matthew Evan Taylor played first a saxophone and then a toy piano, dancer Priscilla Marrero moved across the floor and began interacting with a modular wooden box built by sculptor Ferrán Martín, dressed as either a magician or a petit-bourgeois architect.

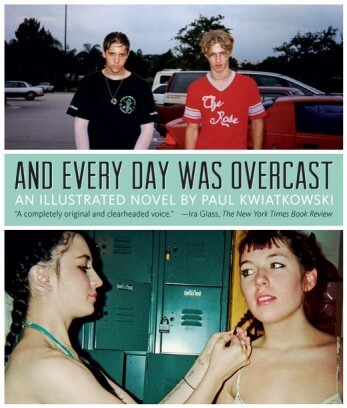

Paul Kwiatkowski’s illustrated novel And Every Day Was Overcast is a series of Erik Persoff stories. Here are bright kids who might have turned out fine in another state but are doomed by the fact that they were born here: two sisters who live behind a biker’s tavern, a kid obsessed with his transistor radio, the daughter of a single mom who believes her kids should do drugs at home “because it’s safer.”

Long time observers of local real estate development might surely ask, “What has gotten into the masters of the universe that control the Miami skyline?” During the last boom, most projects relied on a highly refined economic model. The “vision” was frequently provided by the developer working with zoning lawyers to maximize the allowable square footage and height.

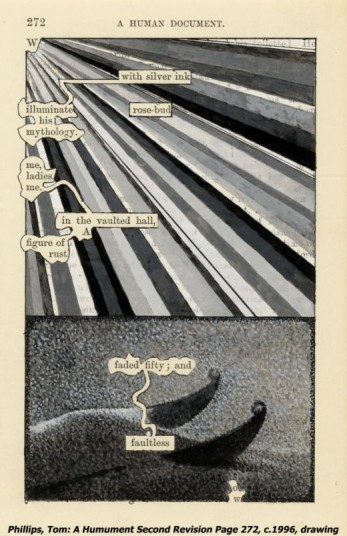

The Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry is one of Miami’s greatest hidden treasures. Tucked away in a two-story penthouse that used to belong to El Puma, the Venezuelan pop star, the archive is the largest collection of word-image works in the country, if not the world. On the occasion of A Human Document at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, The Miami Rail’s Nathaniel Sandler spoke to Ruth and Marvin Sackner about their collection.