The actual content presented via the gallery booths and the related curatorial scenarios was of an elite, cerebral grade. While there were elements of commercial ambition towards private buyers (interior décor-friendly works from Julian Opie, Martin Creed, Gilbert & George and Anish Kapoor were available), the fair’s primary focus appeared to rest on the critical dialogue between artists, artists and curators, and curators and viewers.

Since art is primarily experienced as something that’s been completed—with all of the source material, labor, ideas and time compressed and locked into an object on display—the weirder appendices of its production are rarely seen. The talismans that artists collect and keep in their studios may be enigmatic, banal and functional.

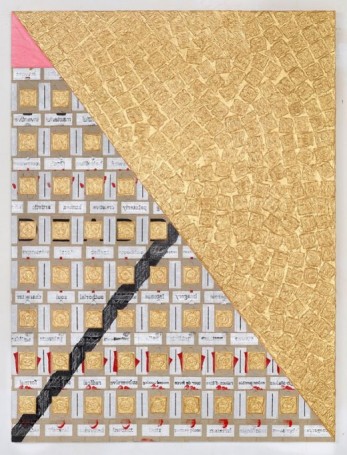

The compositional systems are built up through a series of hunches and dissatisfactions. If something feels familiar I obstruct part of it —or all of it—until it doesn’t anymore. The obstructions add to the buildup. They are as complex in physicality and pattern as the arrangement of images they obstruct. Paradoxically, they amplify what they make invisible.

Dark Nights of the Universe

Daniel Colucciello Barber, Alexander Galloway, Nicola Masciandaro, and Eugene Thacker

The occasion for this text was a four-night gathering in which each contributor gave a talk about hermeticism and Laruelle’s work. A version of each lecture is published here. But it is perhaps another, more tangential occasion that equally colors this work: that of the original text’s translation. “Du Noir Univers” was first translated for an exhibition catalogue for Hyun Soo Choi’s black paintings in 1991. So while the true concerns of “On the Black Universe: In the Human Foundations of Color” are ontological, it is perhaps forgivable to approach it aesthetically. The cover is printed black on black, and the text interspersed with stills from Aaron Metté’s 2012 video which shares the same title as Laruelle’s essay. It looks at home on Mayhem’s merch table.

Just as a language has different dialects that reflect regional variations, slang, or the influence of neighboring languages, art too has a location-specific vocabulary. This is not a new idea—art has been intoned by its surroundings since we killed bears in caves and crossed the plains. Painting landscape became a way to fantasize about territory and chronicle expansion and settlement—a way to stake an aesthetic claim on a place.

For many, the world has always been too much, but the impulse to pluck form, meaning, and understanding from the abyss has persisted with varying levels of belief in possibility and impossibility—both of perfection and imperfection and of subjectivity and objectivity—that makes knowledge at turns an instrument of power, a means to transformative change, and a fleeting game of dizzying fascination.

There is this illusion, this facade of Miami being the next thing, but very rarely do people examine the fact that Miami is a place that exists in the perpetual idea of the next thing. There is no resolution. With this line of thinking, we can compare the city to a hype man backing up a rapper. I don’t know who or what force the rapper might be, so I’ll leave it with that.

Writing Google bait means conquering the listicle in all of its glory and parsing through spreadsheet-data puke until your brain feels like a nickel slot machine. City rankings in particular—worst traffic, largest percentage of beautiful people, most likely to get you laid—capitalize on residents’ pride and our collective obsession with list making.

The Hamburger Bahnhof, a former railway station that now houses the Museum für Gegenwart, or Museum for the Present, is intimidatingly large. Seeing so few works of Kippenberger’s on its clinically austere walls is like viewing an eruption through a peephole, but the exhibition still manages to convey that he was a master of many styles—from abstraction to impressionism to realism—as much as a playful, sloppy interlocutor of conceptual games and unceasing appropriation. He was a man of highs and lows who dragged from the spectrum of his own experience.

The Lost Boys of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan are something of a misnomer. As the story goes, they were misplaced by their mothers and, having gone unclaimed for several days, were taken to Neverland. The Lost Boys barely had time to feel lost before being thrust into an environment that would inevitably shape their personal narratives. The sentiment is the same in Doğan Arslanoğlu’s and Johnny Laderer’s show at the David Castillo Gallery. Here, the story’s protagonists are not lost; instead, they are carving out a home, a narrative composed of intimate experience, nostalgia, the effect of place on a boy’s self-actualization.

I am at the Frieze Art Fair

on May 18, 2013 and it’s

raining on the inflatable

Paul McCarthy sculpture

of Jeff Koons’ balloon dog.

I’m looking at a painting

by Monica Majoli,

at complex forms rendered

in shadow and the geometry

of available flesh,

dissolution of youth in the dark,

this opening in me like a wound

without recourse to a mend

is totally Frieze…

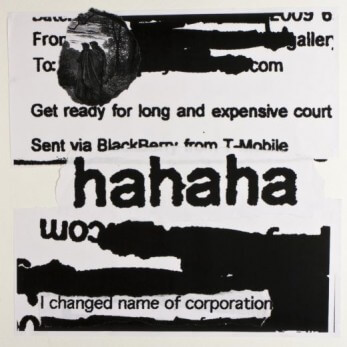

Jonas Mekas is a leading figure of 20th-century avant-garde film and one of the founders of the Anthology Film Archives in Manhattan. Arriving in New York in 1949 after escaping a Nazi work camp in Hamburg, Mekas has worked as a writer, filmmaker and artist. In 2009, Mekas began a long and arduous court battle with his former dealer Harry Stendhal. As of this writing the litigation continues.

In a city whose elevation averages only six feet, Apollonian verticality in architecture is confronted with the horizontal or the Dionysian. Stillness and timelessness are lacerated by accelerated gasps in movements of goods and services.

In July of the year 1900, fisherman John “Old Man” Gomez succumbed to the Florida swamp under mysterious circumstances. He had claimed to be born in 1778 which would have made him 122. The circumstances surrounding his death and his purported age were both indicative of the way Old Man Gomez lived his life. No one really knew the truth about anything he said. As the unofficial patron saint of the Everglades, Marjory Stoneman Douglas said in her landmark tome, River of Grass, that Gomez was known for “tales impossible to substantiate.”

In 1987 T.D. Allman published one of the definitive accounts of modern Miami. Miami: City of the Future was as unapologetic as it was prescient. Since then, he has written on many different topics, including another book on the history of Florida. Published this spring—Finding Florida: The True History of the Sunshine State has received full-page reviews in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Both Finding Florida and Miami: City of the Future will be featured books at this year’s Miami Book Fair International.

Alfred Hitchcock explains what a McGuffin is to Francois Truffaut with a story: It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men on a train. One man says “What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?”, and the other answers, “Oh, that’s a McGuffin.” The first one asks “What’s a McGuffin?” “Well,” the other man says, “It’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.” The first man says, “But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,” and the other one answers, “Well, then that’s no McGuffin!” You see, a McGuffin is nothing at all.

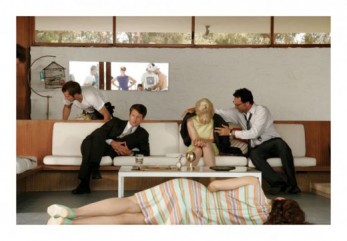

Sussman’s “Rape of the Sabine Women” is a break up of her 80-minute operatic film now projecting simultaneously in five acts at the Bass Museum. Her version of the tale transports Rome’s mythical history to an era loosely set in the 1960s with scenes that recall the neoclassical formula of Jacques-Louis David.

Two velvet club chairs nestle around a table and lamp. Books on shelves are punctuated by objects: an amp, a polaroid camera, etc. Set dressing includes botanical and entomological prints of moths or butterflies. Unremarkable enough not to draw attention to where they lean above the bookshelves, the prints make quiet reference to man’s taxonomic drive to arrange and classify. When Linnaeus named the order Lepidoptera, Samuel Johnson was making his Dictionary of the English Language and Diderot the Encyclopédie, a very different time for the book.

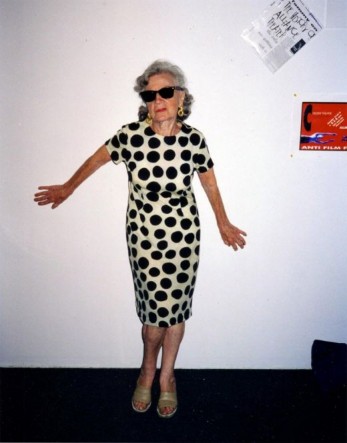

Doris Wishman was an American “sexploitation” director who started her career in the early 1960s and ended it in the early 2000’s in South Florida. Much of her late period work included the assistance of denizens and supporters of the Alliance Cinema and the Alliance Film/Video Co-operative on Lincoln Road in the mid- to late- ’90s. She passed away in 2002.