As the artist Nick Lobo told me over pisco sours at SuViche, Miami is a resort that grew, and grew some more, but it’s still a resort—a place where people come to get away from wherever and whatever they’re from, and whoever they were previously connected to, for a while or forever. The tourist hustle and the short con are as old as the sea and as new as that day’s sunlight. Visitors are welcomed, sized up, and fleeced in endlessly inventive ways that pepper the conversations of locals. Visitors who stay longer begin to welcome, size up, and fleece newcomers, in turn.

While Miami’s art scene is often faulted for lack of depth and conceptual rigor, there is enough intellectual energy here for a group of eight artists (spearheaded by Odalis Valdivieso and Lidija Slavkovic) to organize Fall Semester, a two-day rapid-fire conference where internationally recognized scholars, critics, and theorists came together to consider the city—especially this city, situated on the northern frontier of the global South.

Early on the morning of August 6, 2013, officers of the Miami Beach Police Department spotted REEFA tagging his name on a closed-down McDonald’s. He was adding his tag to a mix of signs and other graffiti that was already plastered on the walls. REEFA, standing at 5’6” and weighing roughly 150 pounds, ran from about six cops until he was cornered a few blocks away. After allegedly resisting arrest, he was knocked to the ground then stunned in the chest with a Taser by officer Jorge Mercado. As the officers celebrated, the suspect went into cardiac arrest. Once delivered to Mt. Sinai Hospital, as stated in the police report, Israel Hernandez “expired.” All he got up on the wall was the ‘R’ in REEFA.

When I tell new acquaintances that I direct Miami’s history museum, invariably they assume I’m making a joke. “Miami?” they gasp. “It doesn’t have any history!”

This fall, the PAMM curatorial staff and I took a museum patron trip to New Orleans for Prospect.3: Notes for Now. This is the third installment in a series of large international contemporary art surveys still labeled “biennial” by the organizers, though four years have passed since Prospect 2. The first Prospect, which opened in November 2008, was organized in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, in large part as an engine of economic and community development for the devastated city. This edition was organized by Franklin Sirmans, head of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In my opinion one of the most talented curators of his generation, he has built a resume heavy on exhibition and publication projects designed to redress the omissions of the Eurocentric Modernist art-historical canon, telling the stories and presenting the artistic achievements of significant yet lesser-known women artists and artists of color from around the world.

L’avenir (looking forward), the 2014 Montreal Biennale, arises from two perspectives that meet somewhere in the middle. L’avenir is French for what is to come. While that appears to be quite poetic, it could refer to anything between death and the pizza that you just ordered. Looking forward––well, you speak English. We have two conditions of the biennale: the expected object and state, and the expectation itself. Spread out over 14 venues, the biennale comprised 50 artists from 22 countries. Half the artists were from Canada; 16 were from Québec. Although it would be incorrect to reduce the art to a thematic checklist, it seemed that the majority of the pieces held a Janus-faced relationship to both the future and history. This relationship appeared structurally in many of the ongoing research-based projects on display. It also appeared in the content of many pieces explicitly dealing with history.

You say that your work is principally focused on the relationships of power that subjugate an individual within a determined context. Do you think that by positioning yourself as any individual you can obviate the fact that you are black? Did your work emerge from some kind of awareness regarding blackness? What are the origins of your work and what were the initial concerns that led you to art?

Lemon City, Lemon City becoming Little Haiti, Little Haiti becoming Little River. The Haitian-infused Miami neighborhoods present a state of flux, a city within a city encroached upon by new development interest while still establishing itself. A stunning photograph of a bush of fuchsia colored tropical flowers is offset by a road side at 62nd Street and NE 2nd Avenue in Miami, a site Adler Guerrier recognizes as a threshold between neighborhoods heavy with associations.

Fleeting Imaginaries is CIFO’s twelfth exhibition of artists funded through its granting program. The title describes the fluctuating, porous notion of a culturally specific sensibility, fitting for a show that brings together artists from seven different countries across Latin America, and yet the show is striking in its visual and conceptual cohesion. Seemingly chance coincidences of overlapping imagery and ideas occur repeatedly throughout the works in the show. Of course, the idea of a distinct cultural imagination is increasingly sublimated in a globally connected world characterized by diaspora and displacement. The problem with increasing interconnectedness is a reduction of linguistic and symbolic variation and hence a gradual homogenization of possible meaning in the face of creeping hegemonies.

Photographs and videos of the people who shaped Punk were recently on view at Ringling College’s Selby Gallery. Presented as joint exhibitions, Low Fidelity: Still Photographs by Bobby Grossman 1975-1983 recalled the style of a previous generation, and Underground Forces: Target Video 1977-1984 offered a time capsule of musicians and artists trying to establish themselves. Together, the exhibitions revealed how the movement continues to be affected by the way it’s represented.

Curated by José Carlos Diaz for the Bass Museum of Art’s 50th anniversary, GOLD assesses the power, effect, and significance of gold through both literal and abstract approaches. The group show consists of 30 works from 24 multinational artists, all unified by the implementation of the precious metal in their pieces. Ranging from photography to sculpture to video, GOLD strengthens concepts of beautification, power, deception, perfection, ancestry, and divinity by encouraging viewers to question the capability of gold.

I just had show at Jumex with puppets, Permanent Revolution. It was my first production turning the museum into a theatre. The play intertwined art and politics: Diego Rivera invited Trotsky to Mexico and stay in his home, Frida Kahlo falls in love with Trotsky. There is an assassination plot with a Stalinist supporter, against Trotsky. It had romance, murder, art, politics, economics, intrigue, science fiction. Everything. My hope was to create something that wide audiences could follow. It’s going to tour Mexico; I’d like it to circulate in theaters.

Daniel Arsham and I grew up in Miami of the 1980s and 1990s. Our lives have intersected throughout the years, but we only became friends after working together on Snarkitecture’s Drift Pavilion for Design Miami/ in 2012. We recently met for breakfast one fall morning in New York to discuss our lives, new projects and his upcoming show at Locust Projects, Welcome to the Future.

It’s been three and a half decades since Julian Schnabel rocked the art world with an exhibition of paintings made on broken dinner plates. Since then, he’s never shied from reinvention, be it aesthetic, or personal. In one of his trademark expansions, he became known as a singular filmmaker, creating works like “Basquiat,” “Before Night Falls,” and “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.” This fall, the Museum of Art | Fort Lauderdale presents yet another side of Schnabel—a painter connected in spirit to Francis Picabia and J.F. Willumsen. On the occasion of this exhibition, Café Dolly: Picabia, Schnabel, Willumsen, he spoke to the Miami Rail editor Hunter Braithwaite.

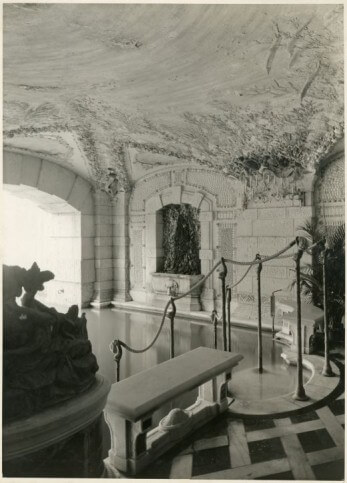

Ornate and extraneous, Robert Winthrop Chanler’s work at the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens can trace part of Miami’s history of wealth, patronage, and aesthetics that developed concurrently with its settlement. It also reminds visitors of South Florida’s almost immediate proclivity towards ostentation and decadence. Chanler was a descendant of some of New York’s most elite families (his mother was an Astor) and his artwork reflected the education he was able to attain, as well as the comfort within which he lived. He’s often characterized as an independent Modernist, someone who blended decorative, international style with fine art. The fantastical, exotic screens, murals, and architectural elements he created were distinct, and have remained unique from his peers. Despite the European avant-garde dominating the memory of the exhibition, Chanler had perhaps the largest American showing at the first Armory Show in 1913, which had particularly sought decorative artists.

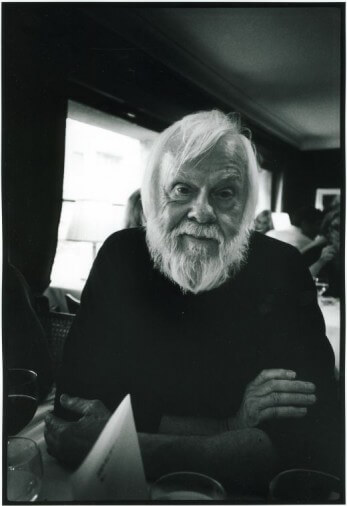

John Baldessari is one of the most influential artists of our time. Born in California during the summer of 1931, he has made art for the past six decades, ranging from his early practice as a painter to seminal conceptual artworks made using found photographs and texts. His projects include artist books, videos, films, and billboards. His artwork has been featured in more than 200 solo exhibitions and in over 1000 group exhibitions in the U.S. and Europe. In 2009 he received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, awarded by La Biennale di Venezia.

By weaving anthropology, sociology, and philosophy, the French thinker Bruno Latour has positioned himself at the frontier of Science Studies, a flexible and searching response to the Anthropocene. This September, he spoke to Miami Rail contributor Camila Marambio about dance, the climate, and the importance of working across disciplines. The conversation occurred on a bench at the Museo do Indio in Rio de Janeiro. The two were taking a break from the colloquium “The Thousand Names of Gaia: from the Anthropocene to the Age of the Earth” organized by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Latour himself.

Claudia La Rocco’s The Best Most Useless Dress is not poetry. That is, it’s not poetry exclusively, but an amalgam of writings, including criticism, handwritten notes, musings, and bits of conversation (also, images) with any combination of these at times appearing within a single piece. The result of all this would be disorienting were it not for recurring themes and phrases, and, perhaps more importantly, the earnestness with which she approaches each poem and the general sense that she has eschewed the desire to provide the reader with something polished and perfect. This meandering, this hesitation, this doubling back creates an intimacy with the reader that excuses some of the haphazardness of the work—no, not excuses—justifies.

Memory has been at the core of human existence from time immemorial. Our fleeting presence seems to be at the root of a pressing need to seize life through memory and remembrance—the only way, apparently, to defeat time.

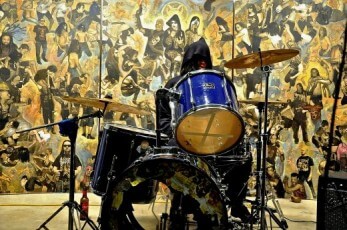

Echos Myron, co-curators Beatriz Monteavaro and Priyadarsini Ray’s exhibition of visual artists and musicians working shoulder to shoulder in South Florida, is a celebration of their scene. It’s a happily crowded show, but I didn’t notice any of the Wynwood-style art that would be a nod to hip-hop’s enormous influence on visual culture. Here, the aesthetic is punk and music is mostly shorthand for rock n’ roll.

Now in its third year, DWNTWN Art Days has grown exponentially with well over a hundred events taking place in downtown Miami on one weekend in September. Fringe Projects has acted as a curated public art exhibition during the weekend, offering a sense of artistic direction over the frantic schedule of activities. While past years have brought interesting projects, the efforts had been a tad scrappy and perhaps underwhelming (likely due to budget constraints). But this year, Fringe Projects has come into its own with a series of ambitious projects that have raised the curatorial stakes. Surprisingly, this is the first year that all of the selected commissions came from Miami artists, something that curator Amanda Sanfilippo mentions was a coincidence. That happy accident has given Fringe Projects a sense of vitality, as not only are many of these artists working outside of their element but are also creating incisive works that address rapidly changing city brimming with dualities.

Stepped up the curb and on beyond the doors of the SculptureCenter, which is housed in an expanded old trolley repair shop in Long Island City, Queens, and I saw an art show called Puddle, pothole, portal, which is thickly about childhood entertainment in the United S of America and, ergo, paradox, poop jokes, and since its art, a didactic treatment of the comic impulse as a socioeconomic response to the ever-changing/ever-malfunctioning of technologies, bodies, systems, selves—and if the latter sounds somewhat trite, it’s intended to, buddy, since everyone and all things do in fact just grow in discrete and sometimes secret ways until their ultimate undoing, a fact which is totally sad but sorta funny, it being both the spring and the void, etc.

The use in useless objects: they make the place feel populated.

People will go to heroic lengths to avoid introspection.

How do I look, by the light of the pale-faced moon?

Nicole Cherubini, a New York-based sculptor with a strong commitment to ceramics, recently opened 500, a solo exhibition at PAMM. Cherubini’s work incorporates a personalized symbolic formalism echoing her interest in utopian craft communities. She spoke with artist Christy Gast about this, as well as feminism, motherhood, and the role of the museum.

“Vanilla Ice was too expensive,” claims Jillian Mayer, through an early morning wry smirk. Apparently Bob Matt Van Winkle of ice-ice-baby-A1A-beach-front-avenue fame quoted his services at $10,000 to be involved in a film for the Borscht Film Festival and then jumped his rate to $50,000 as the deal started coming together. Cold blooded Ice. At the same time as this conversation was happening, Mayer the multimedia artist and filmmaker was serving up coffee and bagels with Publix-brand vanilla-flavored cream cheese at the Borsht Corp. offices. The vanilla-related synergy wasn’t purposeful and the cream cheese was fucking gross.