Justine Ludwig and I spent a lot of time together during this year’s Dallas Arts Week. Previews, openings, after-parties; galas, auctions, dinners. But we never really had a chance to talk. So on Sunday, April 12, I guilted her into picking me up from my hotel at 1530 Main Street, and driving me to her place of work, Dallas Contemporary, located at 161 Glass Street. Not unlike the movie Speed, the following conversation only took place while we were in motion.

One might think it would have been big news in museum circles when Merriam-Webster proclaimed its word of the year in 2014 to be “culture.”

“You can no longer find the original instruments to play Mozart on,” said Janet Eilber, artistic director of the Martha Graham Dance Company.

SONGS FEEL LIKE MUSCLE MEMORY, OR, I’M OFF SOCIAL MEDIA, HMU ON YOUTUBE: A Mythography of Domingo Castillo

Rob Goyanes

How do you write about an artist whose work is about everything but the work itself? This isn’t a fluffy profile of Domingo Castillo. It’s a fluffy profile of conceptualizations of Domingo Castillo.

The journey of the Stalin bronze, sculpted by the infamously outcast Dumitru Demu and torn down in 1962 in a period of De-Stalinization, is equally fascinating, though subject to rumor. The original has by now almost certainly been melted down.

Painting seems to have returned from the dead, again. The frequent pronouncement that painting is dead, followed by the declaration of its eventual resurrection, is an important, but often overlooked part of the modern (and postmodern) artistic tradition.

There are particular states of mind that can be described only as some potential elsewhere, but can’t quite be defined, and that are experienced by creation, particular stimuli, and collaboration. This wording might invite a transcendent, spiritual, or otherwise elevated connotation.

Miami artist Nicolas Lobo is known for giving form to the invisible forces that surround our everyday. Interested in object-oriented thought, his production is both intellectual and process-driven, and his works have revealed interests in a diverse range of phenomena and materials—illegal and informal markets, go-go dancers, and civic infrastructure; concrete, terrazzo, and napalm; and cough syrup, soda, and perfume. For The Leisure Pit, on view at Pérez Art Museum Miami this spring, Lobo used a swimming pool as an outsize tool in an experimental, custom casting process to produce a series of sculptures made from concrete forms submerged underwater and cast inside the pool itself.

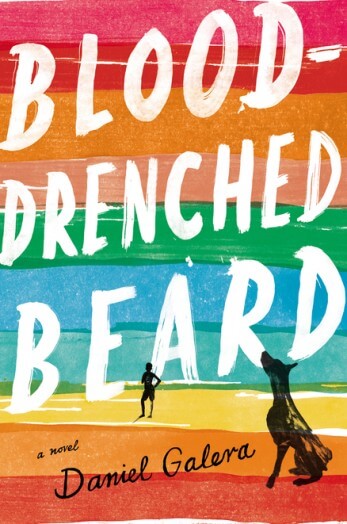

Having recently moved away from the beach and come into possession of a cat, I was a little too thrilled to read this novel about moving to the beach and coming into possession of a dog. Daniel Galera’s Blood-Drenched Beard is the story of young man who copes with a familial legacy of murder and suicide by moving to the Brazilian surf town of Garopaba.

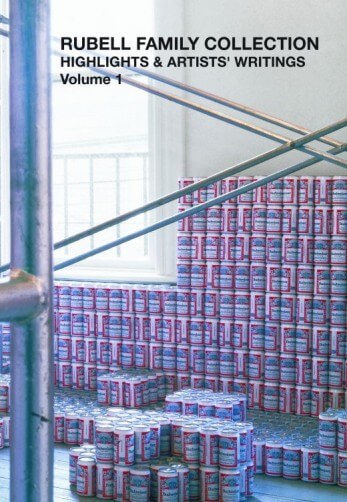

The Rubell Family Collection: Highlights and Artists’ Writings, Volume 1 was published to commemorate the Rubells’ fiftieth wedding anniversary and to mark the twentieth year that the collection has been open to the public. The book encapsulates a selection of 880 works from 250 artists represented in the collection. With more than 6,800 works by 832 artists to choose from, I do not envy that editing job.

One of my favorite artworks is Xu Bing’s 1st Class (2011), a rug made from half-a-million cigarettes. They stand leaning against each other on the floor to form a 40-by-15-foot “tiger pelt,” the stripes changing from tobacco-brown to filter-orange as you move around the piece. It is about decadence and death and industry and nature—from the history of the tobacco trade to big game—and it’s a perfect balance of all of these, humorous and serious at the same time.

The lava lamps mold the room. Pumping to the beat almost like a sentient central nervous system, they feed off the spirit of the place. Happiness, sadness, light, darkness, and beautiful hideousness grinding friendships into late nights and turn late nights toward the imaginary. The massive 8-bit Street Fighter paintings remind us it’s all a game. Put a quarter in. HADOUKEN.

Perhaps no one in Mexico City is more fully engaged with the praxis of merchandise display than the street vendors. Stands hawking nearly identical goods—plastic water guns, cigarette packs stamped with cautionary images of fetuses, striped socks packed in crackling cellophane, and the endless assemblages of Mexican candy (Duvalin, Pulparindo, Lucas Muecas)––are distinguished only by the particular dialogue among the objects. What draws you to this vendor and not to that vendor isn’t a certain stick of gum, it’s the gestalt.

It is a hallmark of grandly chaotic spectacles to be quietly defined by tight parameters, which, though seemingly antithetical to the outcome, actually contribute to the madness of it all. The best example of this might be rules that evolve in children’s playground games: this pole is home base, you can’t run past a building of this color, if you barely brush the chased party, he or she isn’t “it” anymore.

Wander through the galleries on the ground floor of Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), and you can’t miss the imposing, six-foot-tall double painting of Barbra Streisand dressed as a male rabbinical student.

With Robert “Meatball” Lorie as your unofficial tour guide, it would be hard not to see Miami through a different lens.

In April of this year a new stadium in Bordeaux, France, is set to be completed, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, the Swiss architectural firm behind, among many others, the Tate Modern in London (and its 2016 extension), the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and Miami’s own Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM).

During Cecilia Vicuña’s recent busy visit to Santiago, Camila Marambio spoke with her at her childhood home. The relaunching of her 2006 LP “Kuntur Ko” by the independent New York record label Hueso Records brought her home to offer a series of timely performances and rituals composed in response to the destruction of glaciers in Chile.

“Don’t walk. Drive.” I can’t count the number of times I was given these instructions while visiting Miami, regardless of how close I was to my destination. I was offered this advice after having parked just a two-blocks’ walk away from Pérez Art Museum Miami to see a pop-up art project nearby.

Perhaps more than anything else, driving my rental car around the city defined my three-day stay in Miami. This marks a significant departure from my typical visit. Like most art tourists and professionals, I head to Miami Beach in December for the fairs, and if I travel around the city, it’s in a cab or art fair shuttle bus. I don’t rent a car, I don’t expect to get around quickly, and I don’t anticipate spending much time on Biscayne Boulevard. During those trips, I spend most of my days studying the floor plans of fairs and my nights blogging from a perch on my hotel bed.