Peter Eleey is Curator and Associate Director of Exhibition and Programs at MoMA PS1 in New York, where he has organized 20 exhibitions, including an expanded version the Mike Kelley retrospective originally organized by the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Eleey’s much-lauded installation of this exhibition marked the first time that the entirety of PS1’s vast gallery spaces were dedicated to the work of a single artist. Eleey’s current survey of the work of the Austrian painter Maria Lassnig runs through May 25th. Prior to joining MoMA PS1 in 2010, he was Visual Arts Curator at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and Curator and Producer for Creative Time in New York. In town for his talk at Locust Projects on January 16, 2014, Eleey visited artists’ studios and toured the new Pérez Art Museum Miami with René Morales, PAMM Curator. The following interview was conducted on the heels of this visit via email.

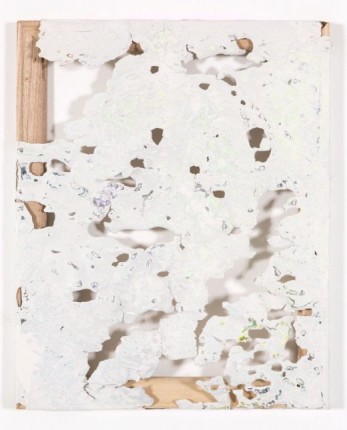

Stepping into the coral-like trove of Solid Single Burner, the LA-based artist JPW3’s solo at Michael Jon Gallery, is like entering a process grotto. There is strong physical and poetic cohesiveness throughout—a transfer of imagery, materials and ideas coupled with literal changes of state as elements dematerialize and incorporate into one another in a self-referential cycle.

The Miami art scene is charged with a palpable tension. At stake is nothing less than the defining qualities of the developing aesthetic gestalt. This tension can best be conceptualized as a battle of different versions of the “simulacrum,” a term that is as old as Plato and has been contested nearly as long. Though a simulacrum can be described as, roughly, an insubstantial semblance, there is also a possibility of dissimulation that lingers about it, for it replicates a particle of reality not as it is but as it might be. Far from a matter of sterile academic debate, how the Miami art community defines itself in relation to the idea of the simulacrum (and perhaps even as a simulacrum itself) will help define an identity still inchoate.

Permission to be Global: Latin American Art from the Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection

Heather Diack

The exhibition consists of an impressive selection of works created between the 1960s and the present, by more than 61 artists from over a dozen Latin American nations, striking a balance between historic precedents and more contemporary manifestations. Divided by four convincing thematic sections, including “Power Parodied,” “Borders Redefined,” “Occupied Geometries,” and “Absence Accumulated,” the exhibition establishes specific points of reference for individual works while flowing compellingly between contexts.

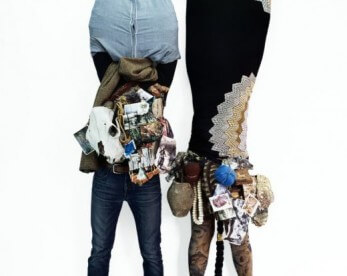

For her new exhibition, Xaviera Simmons splits her practice, roughly, between two physical and intellectual states. Periods of fevered bursts of cultural mining—excavating small truths resident in objects and images found throughout the global landscape—are immediately followed by periods of rest. Specific to the layout at David Castillo’s Wynwood space, Simmon’s Open abandons her comfort zone in terms of curatorial choices and orientation. As every work hangs on the wall, the space morphs into a traditional portrait hall. Large-scale photographs of vaguely human torsos are hung at eye level.

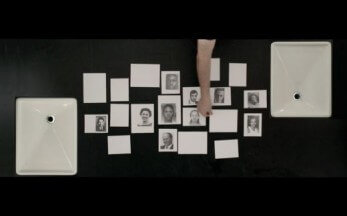

NOW, the survey of artworks by R. Luke DuBois currently on view at The Ringling Museum of Art, is a collection of portraits created from crowd-sourced information. Each originates as data aggregated from sources like Billboard charts, music videos, Manhattan traffic, and the circus. Some portraits consist of complex systems, including his newest, which involves motion-triggered video, and others take on a more traditional identity as flat works recalling the history of the genre. By placing them side by side, curator Matthew McLendon emphasizes transitions both in social ideology and artistic representation.

In BOG-MIA, New York-based sculptor Virginia Poundstone cross-pollinates sculpture, video installation, and photography to explore the transformation of flowers from living things to commodities within the global system of trade. The installation is rich in matter and material, incorporating vinyl, granite, aluminum, and chemically altered roses into her work. At the core of Poundstone’s installation is an inherently complicated species, one that yields a complex world beyond its natural state.

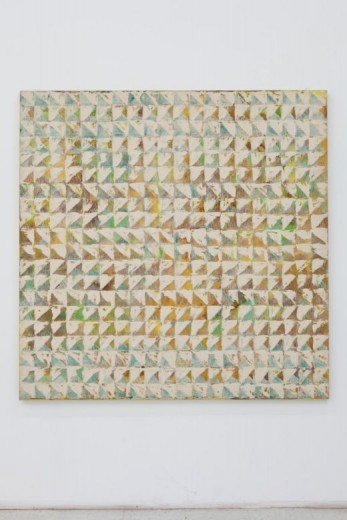

Carol Jazzar Contemporary has been slyly nestled in suburbia for six years, offering respite to the white box-weary, art-fair exhausted public. In the semi-plein air environs of a converted garage, one side fully open to the garden, the works are dually lit by sunshine and conventional gallery fluorescence. Neither fully indoors nor outdoors, both physically and metaphysically, the space operates in the liminal present. For the gallery’s winter show, Present Tense Future Perfect, curator Teka Selman has staged a nowhere zone—between unspecified past and insinuated future.

Public Art In Miami: PortMiami and Beyond

Bhakti Baxter, Jim Drain, Brandi Reddick and Michael Spring

On the occasion of their new public installations at PortMiami, The Rail sat down with artists Bhakti Baxter and Jim Drain, along with Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs Director Michael Spring, and Art in Public Places Curator Brandi Reddick. The conversation moved from the port to the rest of the city to the ideas surrounding public art in general.

The dumbing down of language. People who stop at the top of escalators. Congress. Global warming. Suspiciously happy individuals. War. Certainty. Smokers. Work. These are a few of the many topics griped about in the 70 or so posters by contemporary artists and designers in the exhibition “Complaints! An Inalienable Right,” curated by noted design critic and ridiculously prolific author Steven Heller (160 books and counting). Heller teaches at the School of Visual Arts, so we took this occasion to quiz him on the poster show, hoping to be taught something about complaints and their purpose.

On Sunday, January 9th, I sat down with writer and curator Paola Santoscoy in the VIP room of the Hilton Reforma in Mexico City, the hotel which hosted the first edition of the Material Art Fair. We spoke about the relationship between writing and curating, and the evolution of Mexico City’s contemporary art world.

Between 2005 and 2008 I started by exploring the loose, gestural, and expressive idea of abstraction that I saw in the work of German painters like Albert Oehlen and Gerhard Richter, and which I found really appealing. I wanted to use some of the formal things that I saw in their work to try to talk about the content and mythologies that they had painted out of abstraction. Mainly what they got rid of was New Age-y spiritual crap, but I grew up on that stuff because my folks were hippies.