Awash in light, floated on wide pine flooring and white walls, cantilevered out to mega-foot sculpture galleries, and connected umbilically by stairs indoors and out, the art looks terrific. With all its big guns lined up—there’s Bellows! O’Keeffe! Hopper! Bourgeois!—the show could have sunk under the weight of its commitment to be a review of the Whitney’s history, but, billed as a gourmet tasting of more treats to come, it’s as frisky and promising as a pedigreed colt let out for its first full-length run.

I sit one night eating conch fritters at Beau’s Café on Wheels, a Bahamian food truck that stays, for the most part, on Plaza Street between Franklin and Charles Avenues in Coconut Grove. The dining area is a picnic table in Beau’s driveway. The menu variously includes items such as souse (a kind of Bahamian pork stew), conch salad, fried conch, and conch fritters, served with the ethereal “conch sauce,” the ingredients of which will not be revealed to me.

“More goat than donkey.” This is how my father described B. P. Hasdeu, with an epithet he reserved for men whose intellects he admired and whose views he loathed. Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu was a Romanian writer and linguist, and a prominent figure in the Romanian intellectual community of the late nineteenth century. Hasdeu was the father of Protochronism, the delusional school of revisionist history that exaggerates the feats of the ancient Dacians, a Thracian tribe thought to be the ancestors of modern Romanians. [Note: Protochronism is a historical aggrandizement that was used by Communists to stir up nationalist pride, and is yet another Romanian cultural hemorrhoid, one we will be examining in greater detail in entries to come.] B. P. Hasdeu’s goatlike brilliance had the power to inspire and confound, and the impact of his work can be felt across Europe to this day. To Romanians, however, Hasdeu’s legacy will forever be coupled with that of his only daughter, Iulia.

Los Angeles-based artists Math Bass and Lauren Davis Fisher recently collaborated on the exhibition Math Bass: Off the Clock at MoMA PS1. The nature of the collaboration is interesting, not only because it counteracts the structure of a solo show, but also because the artists are uniquely connected through their simplified and pared down visual language and modes of operation, which incorporate raw materials, identifiable symbols, architectural forms, conditions of space, and shifting spatial perspectives. The artists—who live together in a space that is also shared by Fisher’s studio—discuss here their recent collaboration in the context of the personal and creative relationship it was built on, as well as the physical and theoretical overlaps in their respective practices.

Minutes—or maybe even seconds—into viewing Ryan Sullivan’s paintings at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, the work induced a kind of reflexive mental search algorithm, bringing to mind a succession of names, images, and ideas: Jackson Pollock, Gutai, Robert Smithson, Andrei Tarkovsky, Star Trek, Edward Burtynsky, Paul Virilio, NASA, and global weather imaging.

With Order of Sorcery at Big Pictures Los Angeles, Aramis Gutierrez posits that you can be oppositional by being untimely; punk by being painterly. “Painting is potentially the most embarrassing medium because of its directness and its instinctive connection to skill and taste,” Gutierrez says. “It comes off as a bare-naked avatar of who we think we are, who we want to be, and what we think is going on.”

Intimate Material Systems, a solo show by Miami artist Leyden Rodriguez-Casanova, features a large-scale installation bordered by several recent wall and floor works that, as an ensemble, speak to a characteristic, painstaking inquiry about art, economics, and spirituality consistently present in the artist’s output.

So recently culturally transformed, Miami will likely soon be transformed again, and more profoundly, by avenging nature. If the scientists’ best guesses are true, the rising sea levels ensured by the inexorable advance of global climate change will leave the epicenter of the pop-up hedonism of Art Basel an underwater ruin—sooner rather than later.

Neither art, nor the fitful, fickle affections of the global elite drawn by it, looks likely to staunch this rising tide. Indeed, inasmuch as some of the fortunes on parade each December have been made by dumping carbon into the atmosphere, the fairs play a bit part in the destruction of their own island habitat.

As I read The Argonauts, a list of questions lengthened in my mind. Who should I share this book with? Who, at least within my immediate family, would best relate to Maggie Nelson’s love, her tendencies toward delaminating names, and other habits of language? My aunt, not by blood, who made me mix-tapes of women rockers to listen to over and over again as a small child?

If you go to Andrew Yeomanson a.k.a.DJ Le Spam’s live/work studio in North Miami he will probably make you coffee. He’s got a restaurant-grade espresso machine in the kitchen and firmly believes that if your coffee beans were roasted more than two weeks ago, then they’re stale. The coffee machine is but one of Le Spam’s many prized possessions. Inundated by ceaseless tchotchkes and ephemera, every scrap of available surface area inside the City of Progress—as he calls his studio—is covered with vinyl records, cassette tapes, CDs, 8-tracks, and loads of audio equipment. He estimates there to be around fifteen thousand vinyl records all told, whether they be LPs, 45s, or 78s.

Satterwhite seems to be the ringleader of the world he makes, which is enriched by icons, objects from QVC, impermanence, form, maternal influences, and popular culture. His work investigates memory and desire, piecing conceptions of both together in a saturated and rendered, geometric plane of existence. Initially a painter who felt the limits of being still and later a video artist who found Adobe After Effects couldn’t perform in a way that matched his concepts, Satterwhite transitioned once again and taught himself Maya, a 3D animation software.

Praise may not be the purpose—however we are gendered—but certain secretarial duties definitely have pride of place among the tasks of people who write poetry in 2015.

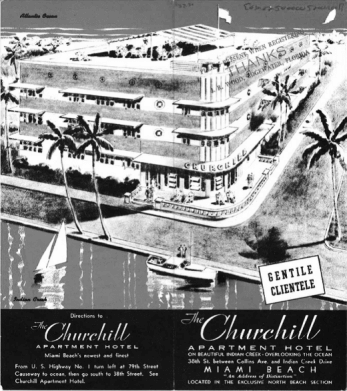

On March 26, 2015, Miami Beach celebrated its centennial, one hundred years of motley history capped off by the Hard Rock Rising Miami Beach Global Music Festival on 8th Street and Ocean Drive. Millions of dollars were spent on a centennial-themed park in the sand, complete with a Ferris wheel and a Hard Rock go-go dancer looming up above the entrance like a gargoyle Salome. Immediately inside, concertgoers passed through a Hard Rock gift shop and confronted the surreal lineup of Barry Gibb, Gloria Estefan, Andrea Bocelli, and Flo Rida.

In a letter to his wife Lucy, John James Audubon described his first impression of Florida as “the poorest hole in Creation,” a disheartening observation in light of Audubon’s reputation as a spirited French-American of indefatigable passion.

The conjuring of monuments and memorial sculpture is the focus of New York- and Cairo-based artist Iman Issa’s series Heritage Studies, which comprises her recent solo exhibition at Pérez Art Museum Miami. Remaking is at the core of Issa’s practice, as is her critique of—or meditation on—cultural transmission, constructions of “the other” through art discourse and museological practices, and the role of art institutions in postcolonialism.

This is what Carol Munder does: she takes pictures, then she prints them.

She shoots black-and-white film with a Diana camera, a cheaply made, medium-format, plastic-lensed device first produced in the 1960s, sold to five-and-dimes by the gross, and often given away as novelties.

Diana cameras are the original fuzzbox of the photography world. They distort, they vignette, they are riddled with light leaks, and their ability to focus is largely theoretical.

From the perspective of this Northeasterner and Miami novice, the city of Deco and Dolphins cuts a charmingly vexing silhouette. Like for many outsiders, my concept of Miami before I ever came to see it myself was a caricature: excess and tits lit by palm-frond sun shadows and neon hotel signs. And to be sure, those images are here. Caricature is, of course, always based on truths. And that’s one of the things about Miami I came to love—its un-self-conscious willingness to live up to its shit.

The room is walking

into a woman. It’s lying

to you again—hasn’t learned.

The room is walking into a woman

and he claims this time

he has evidence. A telephone

dangles from his white collar neck. Right.

That’s my cue.

Existing between abstraction, graphic art, Adobe CS, and the screen, Jesse Moretti’s work aims for a place where the supposedly discrete states––flatness/dimensionality and analogue/digital––merge. By creating a feedback loop between digital and material space in the studio, she collapses and unifies the pictorial plane. Born in Miami Beach, Moretti received her MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in 2013. She has received residencies at MANA Contemporary ESKFF, Jersey City, and Pioneer Works Center for Arts and Innovation, Brooklyn.

Alternative Contemporaneity is a courageous attempt by director Babacar M’Bow, artist/curator Richard Haden,and educator Adrienne von Lattes to reclaim contemporary art from what M’Bow calls in his catalogue essay the “tiny, economic elite” who consider it (or, rather, its possession) solely as currency in the churning global market. For the MOCA team, contemporary art is nothing less than an exploration of what it means to be human amid the economic, social, and political systems that dehumanize.