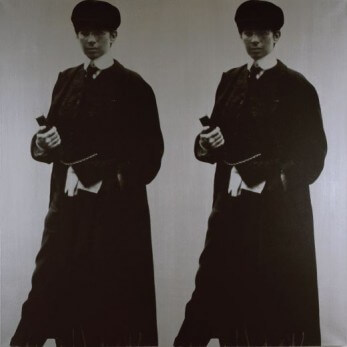

Wander through the galleries on the ground floor of Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), and you can’t miss the imposing, six-foot-tall double painting of Barbra Streisand dressed as a male rabbinical student.

Perhaps no one in Mexico City is more fully engaged with the praxis of merchandise display than the street vendors. Stands hawking nearly identical goods—plastic water guns, cigarette packs stamped with cautionary images of fetuses, striped socks packed in crackling cellophane, and the endless assemblages of Mexican candy (Duvalin, Pulparindo, Lucas Muecas)––are distinguished only by the particular dialogue among the objects. What draws you to this vendor and not to that vendor isn’t a certain stick of gum, it’s the gestalt.

One of my favorite artworks is Xu Bing’s 1st Class (2011), a rug made from half-a-million cigarettes. They stand leaning against each other on the floor to form a 40-by-15-foot “tiger pelt,” the stripes changing from tobacco-brown to filter-orange as you move around the piece. It is about decadence and death and industry and nature—from the history of the tobacco trade to big game—and it’s a perfect balance of all of these, humorous and serious at the same time.

Miami artist Nicolas Lobo is known for giving form to the invisible forces that surround our everyday. Interested in object-oriented thought, his production is both intellectual and process-driven, and his works have revealed interests in a diverse range of phenomena and materials—illegal and informal markets, go-go dancers, and civic infrastructure; concrete, terrazzo, and napalm; and cough syrup, soda, and perfume. For The Leisure Pit, on view at Pérez Art Museum Miami this spring, Lobo used a swimming pool as an outsize tool in an experimental, custom casting process to produce a series of sculptures made from concrete forms submerged underwater and cast inside the pool itself.

SONGS FEEL LIKE MUSCLE MEMORY, OR, I’M OFF SOCIAL MEDIA, HMU ON YOUTUBE: A Mythography of Domingo Castillo

Rob Goyanes

How do you write about an artist whose work is about everything but the work itself? This isn’t a fluffy profile of Domingo Castillo. It’s a fluffy profile of conceptualizations of Domingo Castillo.

Justine Ludwig and I spent a lot of time together during this year’s Dallas Arts Week. Previews, openings, after-parties; galas, auctions, dinners. But we never really had a chance to talk. So on Sunday, April 12, I guilted her into picking me up from my hotel at 1530 Main Street, and driving me to her place of work, Dallas Contemporary, located at 161 Glass Street. Not unlike the movie Speed, the following conversation only took place while we were in motion.