The Miami Art Museum, en route to a better home and hanging gardens, has staged a love letter to the city as its final show in the old place, an epistle both endearing and sly. Meet the Miami we all know—its flashy environment, natural and built; its hidden narratives, historical and current; its backstories, real and imagined; its ready-mades, and its artifice.

Another part of the enjoyable puzzle of spending time with Price’s sculptures is wondering how the artist worked his fingers, hands, and even arms inside them. “Sourpuss” (2002), for instance, one of the sculptures on loan from Gehry’s own collection, is a mold- and rust-colored ghost of sweeping, bulbous forms.

The first thing one has to ask is whether personal selection isn’t the most reactionary form of engagement with the concept of labor and the complexity of its descriptions. In the video, the invited parties justify their choices by alluding to family history, by comparing railway workers to 9/11 first responders, by reading religious and mythological references in the poses of the laborers depicted, by relating stories of provenance, and by drawing art historical correspondences.

For his new show, Daniel Milewski takes the down-home objecthood of Americana and launches it into the nebulousness of pop cultural trivia, art historical references, and the artist’s own sentimental education. If there was ever a time to imagine some kind of union between Ted Nugent and Sophie Calle, as filmed by Cameron Crowe, it would be now.

Though steeped in similar conceptual concerns, McElheny’s film, The Light Club of Vizcaya: A Women’s Picture, lacks the aesthetic and seduction central to his widely-recognized installations. Incorporating meticulously hand-blown glass, the sculptures appropriate Modernist design and art objects, fraught and progressive at once, that propose a new world using often-impossible models.

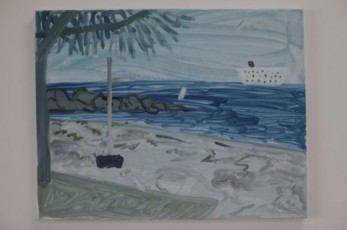

For two weeks this January, Chicago-based painter Tyson Reeder took his practice en plein air to South Florida. The carefree, playful act of painting on Miami’s beaches contained just the sort of atypical ingredients you would expect from an artist who has orchestrated art fairs in bowling alleys and in the dark.

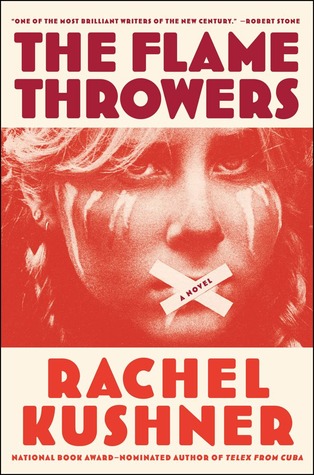

“I come from reckless, unsentimental people.” Thatʼs Reno, 22-year-old motorcycle-racing art-school graduate and heroine of The Flamethrowers, Rachel Kushnerʼs brainy, provocative, and bristling follow-up to her National Book Award-finalist debut, Telex from Cuba. The year is 1976.

With her Paper Folding Series, Odalis Valdivieso uses the relatively new and quickly-evolving trajectory of digital photography against itself. The self-destruction is, however, in a well-composed guise. It is difficult to view these pieces as self-destructive because Valdivieso creates moments of nostalgia for Modernist aesthetics through a combination of image capturing, printing, cutting, painting, re-scanning, and digital manipulation.