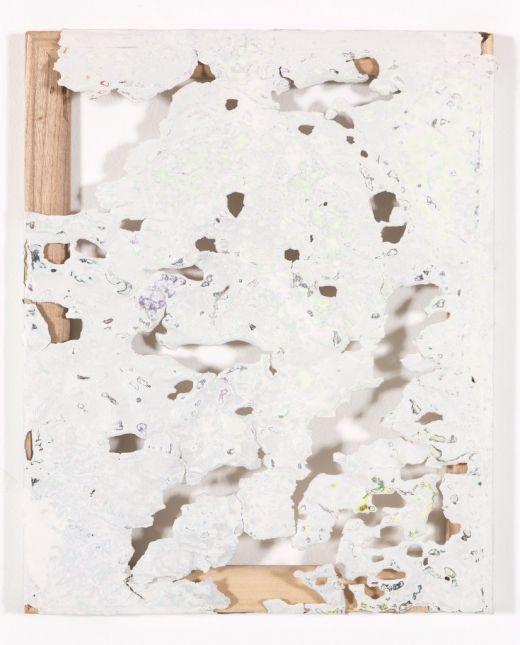

Kadar Brock, deredemilpiiiiii, 2007-2014. Oil, spray paint, and house paint on canvas, 20 × 16"

ALEX BACON (RAIL): How did you begin painting?

BROCK: Between 2005 and 2008 I started by exploring the loose, gestural, and expressive idea of abstraction that I saw in the work of German painters like Albert Oehlen and Gerhard Richter, and which I found really appealing. I wanted to use some of the formal things that I saw in their work to try to talk about the content and mythologies that they had painted out of abstraction. Mainly what they got rid of was New Age-y spiritual crap, but I grew up on that stuff because my folks were hippies.

RAIL: So you wanted to use the very thing, spiritual content, that had been banished from the work of artists like Oehlen and Richter in order to reinvigorate that kind of painting for a contemporary moment?

BROCK: Yes, I wanted to reconnect those links in the chain, or at least talk about them. I took some of Oehlen and Richter’s brasher, more emptied out, “bad painting” cues and structured them in triangular shapes that echoed crystalline structures, and sweeps in space, both of which I related to a digital New Age aesthetic with the addition of things like sun spots, deep perspective lines, and glowing, aura-type effects.

Slowly this brasher, brighter abstract work evolved into a more succinct, specific, mark-focused, minimal brand of painting. As I was working on that stuff, getting more and more into it, I realized that the way I was thinking about abstraction in general was based on a certain relationship to the hand-made mark, and to a belief structure that surrounded artists’ actions, and to the role of the artist, and how that was manifested in the gestural acts of painting. That became something I was more and more focused on. So I started paring down the paintings and making them way more geometric, just repetitive patterns and what not. I got to the point where, instead of wanting to paint, I got really excited about setting up a motif, executing it in either pen or marker, and then using that as a stand-in for the idea of gesture, and the idea of action, and the idea of the artist’s mark, and all that.

Then I started whitewashing those marks out after I had made them, all to try and see how much of it stuck. Simultaneously, as I was doing that, I wanted to figure out a way to strategically take out some of the conscious decision-making I was using to set up my compositions, and also to allow for more chance to come in. Essentially I wanted to set up a conceptual framework for talking about the contemporary painter’s relationship to gesture and to mark-making and to the idea of the artist.

I was also beginning to correlate the act of painting abstractly to the casting of spells in the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons. I thought that was really appropriate because there’s this whole relationship with belief that goes into abstract painting and the desired generation of an affective aesthetic experience. I was rediscovering this Dungeons & Dragons book that I had from when I was a kid. I was reading it and thought, “Oh, these would make great titles.” So I started titling some of the pieces from that book. Then I thought that I should start not just appropriating the titles, but starting to use the game’s rules as a way to set up ground rules for my painting practice. It segued into using dice and having an avatar. All of it allowed me to introduce a system that removed myself from the act of making a gesture, allowing it to become this autonomous thing, which could potentially be either expressive or non-expressive.

I had gone to Argentina for two and a half months with my girlfriend. We were down there doing some projects and I didn’t have any way to really make art, other than to hash out ideas and keep a journal and do sketches and stuff like that. I was really mulling over and over and over how to flush out this avatar dynamic because I had discovered that it was important to me, insofar as a catch-all to talk about my relationship to painting, as well as a way to set up a fence between the act of making a painting, and what making a painting means, and what my relationship to art is as an artist, and all that.

Then that suggested the idea of annihilating these earlier paintings that were expressive, or supposedly expressive, and that were potentially about a minimalist relationship to gesture and abstraction, and that were concerned with this different belief structure than the other abstract paintings that were around. It also dawned on me that I was excited about the idea of taking a piece of art and totally objectifying it. It was no longer a place of action, but a thing to be acted upon.

RAIL: How exactly did you come to the idea of sanding down the canvas?

BROCK: Well with some of those works, the seven paintings before these guys with the sparse markings and just the roller bars and all that, I had been sanding those. The whole process is to scrape down and sand down the “original” painting, and whitewash it, and sand it, and then whitewash it again, and then layer color, whitewash that, and then sand that, and then repeat the process until it gets to a place where I’m subjectively satisfied.

RAIL: Just to get a certain surface effect?

BROCK: I guess so. I think it just happened because I was making these marks, and I was painting over them, and I was essentially starting to treat my paintings in literally the same way I would treat a wall. If you have spray paint on your wall, the only way to cover it up is to use primer, and white spray paint, and sanding paper, you sand it away, and you prime it, and you sand it, and you prime it, the same way you repair walls, and try to get them back to a clean state. So I just started treating my paintings in that same way. It was always really connected to this very practical labor thing that came out of building out my studio.

RAIL: So all of a sudden you sanded through a canvas, making a rip or hole, and that seemed like something, rather than nothing?

BROCK: Yes, the impetus to start scraping all these down was to see what would happen—my past self has a really good sense of composition, and my present self doesn’t care about it that much.

RAIL: Maybe you could talk a bit about how those activities factor into your life; those hours spent sanding the canvas, that kind of repetitive, mundane, or at least theoretically mundane, kind of activity?

BROCK: Sometimes it drives me crazy, because, for example, the last two days I’ve done a good 10-12 hours of sanding each day. Which kind of drives me a little nuts. When it goes on for that long I end up watching things on Netflix half-heartedly while I’m doing it.

RAIL: There’s still this fantasy of the artist as the monk, in the studio, shut out from the world.

Installation View of Kadar Brock’s SCRY 2 at Gallery Diet.

My paintings are all very labor intensive, they take a really long time, and I think that’s great. There’s something more real and practical, and satisfying and grounding about repetitive labor than something that’s about just some obscure erudite decision that is supposedly meaningful to the people that read a text. There’s something really reassuring and basic about labor—doing things with your hands, spending eight hours a day doing it, having it be a physical thing, as opposed to anything else. There’s a real connection to this idea of the everyday, and to the mundane and to the physical, repetitive, biological that is connected with physical labor, and repetitive actions, and those are all things that are super profound for human beings, especially in our culture that is not as connected to that sort of thing anymore, and that wants you to stay out all hours of the day and not be connected to any kind of real biological rhythm.

RAIL: It seems interesting to go back to this idea of doing the process while having, at times, one eye on Netflix. But you’re not fully in Netflix, and you’re not fully in the painting. You have to pay attention, but not pay too much attention.

BROCK: Yeah, exactly, you don’t want to be too conscious of it.

RAIL: And that’s maybe a sweet spot, right? That hard-to-find way of working—whether you use Netflix or something else—so as to make the kind of mark that is purposeful, but not over-determined.

BROCK: Yeah, exactly. I mean I was even thinking about it the other day. I wouldn’t be surprised if the aesthetics of these paintings ends up correlating to, say, the length of my arm, the size of my hand, you know what I mean? Not like I want it to, you know, it’s not like there’s anything necessarily profound about it, but just the fact that it is very correlated to this physical action makes it appealing.

RAIL: I mean in a way you’re the only one who can make this painting. If you, say, made a recipe, so to speak, for the painting, and you had another person manufacture it—it would look different because it would be based on all of that person’s individual idiosyncrasies.

BROCK: Yes, it would be a different action, because made by a different length of arm, with a different way of moving the disc around, and all that seemingly small stuff.

RAIL: It’s another way to imbue the work with life, right, because it means that the work’s life is not only what you imbue in it as the maker, but also the kind of life that the painting has as it moves through the world.

BROCK: The physical object’s movement through this ecosystem I have created in my studio.

RAIL: Right, we were talking before about the more traditional life of a work as it moves from gallery to collector to museum, etc. But you also set up a kind of system where there’s no single, definitive, finished phase in the act of working, let alone a fully complete painting. Instead, there are all these stations, and in a way it’s not even that there is a preset number of stations, because tomorrow you might imagine a new life for some material, and then there’s a new aesthetic direction that arises. In a way your studio really is a kind of ecosystem because that implies evolution. It also implies—which I like—that it’s also related to other ecosystems, so that circulation is not simply internal to some hermetic system.

BROCK: I get new information, I get new inspiration, I get new friends, stuff comes in, stuff goes out. So, yeah, all these paintings end up coming back to the studio, and leaving it, in one form or another!