My grandfather raced on the beach course at Daytona in the late ’40s and early ’50s. Two miles up the beach sand and two miles back down A1A. He was never seriously injured but bore close witness to a spectator being struck by racers and all parties losing their lives. My father began racing in the early ’60s as pavement tracks took precedent over dirt. As speeds increased so did injuries, and he saw his fair share challenging to be one of America’s best. He learned early that broken bones were merely an inconvenience, rather than a deterrent from doing what he loved. At 12, he ran over his own leg at the now defunct Hialeah Speedway. A month later he cut his cast off with a hacksaw and decided not to return to the doctor.

Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, offering a 200-year survey of visual culture from the Caribbean Basin, results from more than a decade of devoted work by curator Elvis Fuentes. Taking as its point of departure the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804)— a pivotal moment that changed the Caribbean’s dynamics with Europe—in the history of the area, the exhibition rejects the reductionist and extended chronological vision of a place where the coexistence, persistence, and overlap of different historic eras is one of the most outstanding endogenous characteristic.

Held in the city’s dormant summer months since 2012, The Miami Performance International Festival offers artists from the States, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Europe a public platform far from Art Basel. Organized by artist and curator Charo Oquet the festival is unrefined compared to market-driven fairs, allowing artists to express challenging themes that emphasize the pressures of conformity and emotional states of being.

Much has been said about the ways that Art Basel has transformed Miami’s relationship to the international art world. Once a year in December, when it’s cold and gray in New York, London, and Berlin, the art jet set congregates in the waterfront hotels of South Beach to buy art, talk shop, cut deals, and party hard. Over the last 12 years, the number of fairs has grown from one to around 20, attendance numbers have reached six figures and the cash injection into the local economy is now estimated at over $500 million a year. The media hype stresses the benefits of high-profile culture, which, like it or not, spurs gentrification on the one hand, and public and private investment in local cultural institutions on the other.

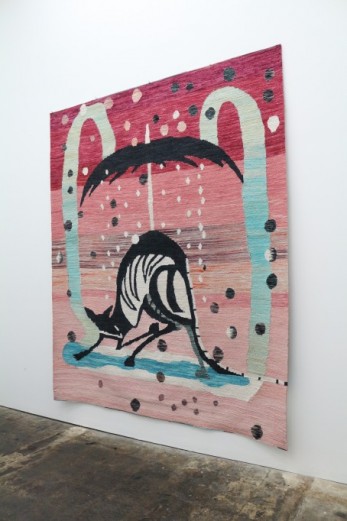

There are two elements of the work in Yann Gerstberger’s recent show that could warrant attention individually: the imagery recalling Miro or Picasso as much as ’80s graphics or ancient, totemic forms; and the work’s material presence as rugs or textiles. Both elements dominate the viewer’s initial encounter. Large rugs of thick strands of dyed mop-head material host mysterious, simple forms in a palette of pinks, magentas, sky blues, whites, tans, and blacks. The atmosphere is warm and light, and the objects suggest ancient modes of making even as they remain obviously contemporary.

Until 2006 it was still possible for the entire Biennale to be hosted inside the KW Institute as well as in vacant buildings in the Mitte neighborhood. But recent development in the neighborhood has forced Biennale’s curators and organizers to expand to venues outside of the city center. While this may have extended travel times between venues, it introduced the artists and audience to parts of the city outside of the expected cultural hubs that have flourished over the years. Most importantly, as noted by Gabriele Horn, Director of KW Institute, it came to reflect the “diversity, social and spatial heterogeneity, dynamism, mobility, and simultaneity of different urban areas that opens up the varied potential for the city’s future and its multiple publics.”

Efficient and peaceful, the Tallinn airport was a marked improvement upon infernal Miami International. The cab driver’s English was better than those in Miami. Come to think of it, everything here seemed better than Miami, especially the weather, which was worse than Miami’s, but simply by being bad offered a change and, with that, excitement. “Nothing is harder to bear than a succession of fair days,” Goethe says. Luckily, with its near-constant cloud cover and regular showers, I didn’t have to worry about that in Tallinn.

On a rainy day in May, the Miami-based artist Christy Gast and I decided to distract ourselves from working on the exhibition project that had brought us to Paris by going to check out Thomas Hirschhorn’s latest installation Flamme Éternelle at the Palais de Tokyo. It was a welcome surprise, upon entry, to discover that Hirschhorn had chosen to make his exhibition free of charge and had built a structure and a communication/signage system that bypassed the admissions desk and descend directly into the massive sub-floors of the art palace. Steered, as we were, by Hirschhorn’s usual language of cardboard, packing tape, and philosophical slogans, we soon found ourselves in what felt like a jerry-built city constructed almost entirely of tires and where the reigning feeling was “anything goes.”

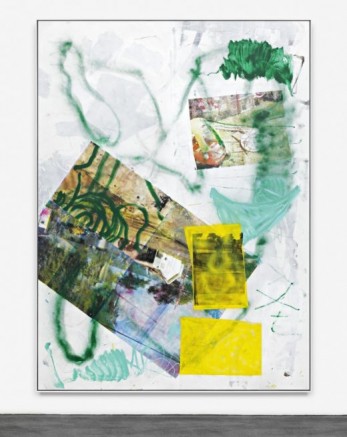

Three Belgian artists, represented by a gallery in Berlin, stage an exhibition in London concerning life in Florida. Chew on that. Chew slowly and hope it stays down. Lieven Deconinck, Gaëtan Begerem, and Robin De Vooght are three multidisciplinary artists who have meshed their names together to form Leo Gabin. For their recent solo exhibition, part of the alternative Inside the White Cube series at White Cube (Mason’s Yard) in London, Leo Gabin addressed Florida as a modern Limbo: where those occupying it lie in wait, in longing but with little hope, for a future above and beyond their current circumstances.

If any city is poised to invent its own idiom, it is here.

In this sprawled out, inconclusive phrasing of a city.

If Miami were punctuation it would be a colon: porous and prophetic.

In the spring of 2013, Miami artists Loriel Beltran, Domingo Castillo, and Aramis Gutierrez started a gallery in Little Haiti called GUCCIVUITTON. I didn’t fully get the irony of the name until I attended an almost empty “collectors night” there, hosted by the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami. When I asked a museum staff person why it was so sparsely attended, she said “we think a lot of our members drove up, looked at the neighborhood, and kept driving—I mean we’ve had members not come to events because there wasn’t valet, so you can imagine they aren’t ready to stop in Little Haiti!” Despite such collector trepidation, GUCCIVUITTON has mounted some of the most interesting and eclectic exhibitions anywhere, with a sensibility that could only come out of Miami—in fact, that is their stated mission: to explore a colloquial South Florida aesthetic in its many forms. One sweltering afternoon during their Chayo Frank exhibition Gutierrez and Beltran walked me through an oral history of GUCCIVUITTON.

The first time I saw Beach Day perform was from the periphery of a sweaty mosh pit at Gramps Bar in Wynwood, where the band opened up for pop-punk icons the Thermals. Skate videos showing epic, painful wipeouts ran continuously on loop, projected against the side of an adjacent building. A haze of pink lighting enveloped the trio, tempered only by a few Christmas lights slung sparsely and haphazardly inside the small performance tent. When slender lead singer Kimmy Drake introduced herself as “just a Kendall girl,” referring to the blasé Miami suburb known mostly for its Barnes & Noble, audience members stirred restlessly. But then she froze the crowd with vocals that would’ve made Jack White, Kim Deal, and Phil Spector each nod their heads in tacit, rhythmic, hypothetical approval.

Thanks to growing up in Britain, my knowledge of the American West is largely based on The Lone Ranger television show and John Wayne movies. Luckily, these unimpressive credentials did not impede my ability to make sense of, and appreciate, Cara Despain’s exhibition Cast Set, presented in the project room at Emerson Dorsch. Like most viewers, I was able to access the popular tropes associated with the American West utilized by Despain, which the gallery text describes as being “embedded in our collective psyche.” The idea of a collective psyche strikes me as somewhat suspect, since it assumes a degree of exposure to Western culture (in the global sense) that is by no means universal.

Miami’s artists who have been around long enough to have seen and inhabited the city’s waysides—those places just beyond the reaches of gentrification and development, but whose fate will likely meet both—know a familiar narrative. It goes like this: We jump from ruin to ruin and ride out the final stages of spaces bound to meet a very different future, lingering in the dingy moments that comprise its past before it is razed, renovated, or beautified in anticipation of a soon-to-be-changed neighborhood. In the dead of summer, with the hustle of the art fairs and the perfume-soaked, diamond-crusted upper level affairs on holiday, the artists can assemble themselves in their sweaty lair in true form. In this instance, it takes the shape of an exhibition of artists who are working, or have worked, in Little Haiti.

Urbes Mutantes: Latin American Photography 1944-2013 announces itself first as an exhibition of street photography. The mobility of the photograph, the viewer is told, lends itself synchronically to the rhythms and transient excesses that compose the chaos of city life. This evocative intimacy between photography and the frenetic charge of the urban strike a particular resonance in Latin American cities. Such is the curatorial premise of the exhibition, organized by Alexis Fabry, curator of the Poniatowski collection; and María Wills, a curator at the Museo de Arte del Banco de la República in Bogotá; currently presented at the International Center of Photography in New York. Consisting of more than 300 images selected from the private collection of Stanislas and Leticia Poniatowski, Urbes Mutantes offers an incredible survey of photography across 10 Latin American countries.

There is dignity in emerging from the gym, curved from glass, ripe

in the valet wait, all of us, together, breaking under the super moon,

mid-career Drake on the satellite radio, all of us, listening, leather,

fake leather, whatever. There is dignity in the way the wind moves

through the palms like a venetian shade in a rented room.

In 1994, when I was Chief Curator for Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, I testified before the Commission on Chicago Landmarks in favor of protecting the 1951 Arts Club of Chicago designed by Mies van der Rohe. For my troubles I got called a carpetbagger in the city’s newspaper of record. Since then, I have come to realize that name-calling is standard practice in preservation “debates.”

I’ve been involved in a few other efforts to protect landmarks, but I don’t consider myself a preservationist. Why? Because the “ist” in preservationist implies an “ism,” an ideology. And the ideology of preservation—or how it is should operate in practice—is never very clear, at least not to me. Perhaps that is why name-calling is so prevalent as the typical preservation debate plays out like a media smackdown between private property owners and preservation activists, generating more heat than light.