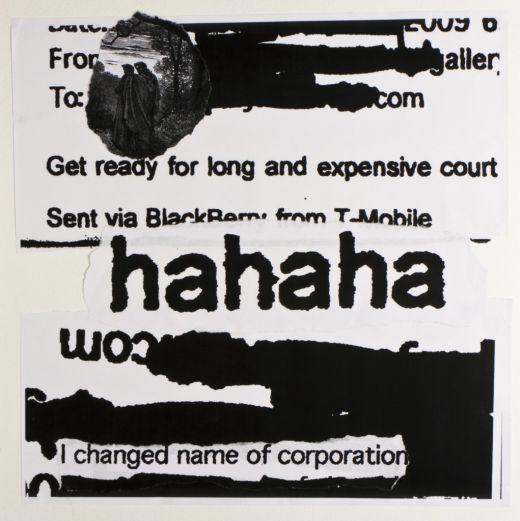

Jonas Mekas, Outlaw: Letters from the gallerist to the artist (#7), 2013, acrylic and xerox collage on paper. Courtesy the artist and Microscope Gallery.

One of the disputes in the case involves several of Mekas’s artworks which were stolen and traded in exchange for food and drink by Stendhal to Cipriani S.A., the Luxembourg-based corporation which owns Harry’s Bar in Venice and recently opened the Cipriani Downtown restaurant in Miami’s Brickell neighborhood. A work by Mekas featuring images of Andy Warhol is prominently displayed in the Brickell restaurant’s dining area. The Miami Rail asked Nicolas Lobo to find out more from Jonas Mekas about the court case, how his work ended up in Miami, and his recent show at Microscope Gallery in Bushwick, Brooklyn.

NICOLAS LOBO (RAIL): I want to ask you about the situation you experienced recently, the lawsuit regarding the theft of your work and also the distribution of some of that stolen work throughout the Cipriani chain of restaurants. Can you describe the process of realization when things went sour with the gallery? What feelings did you have at that moment?

JONAS MEKAS: When in 2005 I joined Maya Stendhal Gallery, I was warned to be careful by several artists who had dealings with the gallery. But I had complete trust in humanity. My wake-up call came with the $60,000 purchase of my installation “Birth of a Nation” (1997) by the Museum Ludwig. Harry Stendhal informed me that due to the “huge amounts of monies” he had spent on my shows, the gallery had the right to keep all the sales monies. I didn’t get a penny from that sale. The second blow came soon after, when the gallery refused to return a set of “Grapefruit” cards that Billie Maciunas, George Maciunas’s wife, had stored with me and which I, foolishly, had lent the gallery for a show. Harry Stendhal first insisted that I had sold them to him. Later, seeing that his story would not hold water, he switched to saying he received them from George Maciunas’s sister.

RAIL: Has this experience changed the way you relate to people you work with? Are you more cautious or mistrustful now?

MEKAS: No, the case of Harry Stendhal has not changed my trust in humanity or galleries. I think the case of Harry Stendhal is a unique case bordering on sickness that should be of interest to psychiatry schools.

Installation view of Jonas Mekas’s piece at Cipriani Downtown in Miami. The candid nature of this photograph is due to the restaurant’s photography ban.

MEKAS: Artists should not be silent about their bad experiences with rogue gallerists. But I have to tell you that in order to avoid bad publicity, and continue their rogue practices, rogue galleries, after they get sued, and after a settlement is made, ask the artist to sign a pledge not to reveal the conditions of the settlement or talk about the case. This is what has happened with the Maya Stendhal Gallery (later renamed Harry Stendhal Gallery). I think artists should not sign such pledges.

RAIL: This show at Microscope is very much in line with your long-standing diaristic approach to making your work. Do you feel some catharsis by putting this negative experience in the public eye?

MEKAS: I did not make the “Outlaw” collages, in which I am using Harry Stendhal’s e-mails to me, as catharsis. No. But you are right about the diaristic part. I use in my art everything that happens in my life. Harry’s e-mails represent a very strong and unique reality, loaded with content—content full of anger, sickness, arrogance, threats, obscenities, put-downs, bragging, etc.—that makes the collages uniquely aggressive. I do not know of similar examples in art history, although I know there must be artists who have done something similar. No, I didn’t do it for catharsis. I did it to throw it back into the face of the author of those e-mails, and at the same time, to bring it to the attention of a wider public. I want to put an end to at least one rogue gallerist’s free drinks at Cipriani.

RAIL: Regardless of the way your work was acquired, how do you feel that it is hanging in exclusive restaurants like Cipriani Downtown. Is this an undesirable place for the work to be seen?

MEKAS: After the cases of Museum Ludwig and “Grapefruit” cards, I had no choice but to take Stendhal Gallery to court. During the discovery work done for the case by my lawyer, a whole Pandora’s box full of my other stolen and sold works was opened. The gallery sold a whole series of my works without telling me or paying me. Three major pieces, 40-image installations devoted to Warhol, Elvis and Fluxus, for which Harry received $290,000 in free drinks ended up with Cipriani. I do not mind that they are hanging at Cipriani since Harry’s Bar is my favorite bar in Venice, Vienna and Paris—where you can touch Hemingway’s typewriter—but I certainly mind the way they got there! One of the curious discoveries made during my case was that Harry Stendhal was not selling my works to the collectors, where it could be very easily become known. He was, instead, selling them to corporations, of which there are too many to count. His idea was that this way nobody would ever find out about the sales. Clever idea!

RAIL: There are recently published press releases online authored by Harry Stendhal claiming that a settlement has been reached in the dispute between the two of you. Is this true?

MEKAS: No the case is not closed, not as of today, which is August 4th, 2013. The case is in the stage of settlement negotiations. But ever since the beginning of the negotiations, which are still hanging in the air, Harry Stendhal has periodically been issuing statements saying that settlement has been made. It’s his game. I think it’s very important that I tell you what the term settlement in cases like this, really means. One may think, very very falsely, that it means that the artist has finally received some justice. Not at all! Take my case. After four years of litigation, which has cost an immense amount of money, I have come to the point where I have to consider two choices. Choice one: I could continue the court case. But the American court system allows the accused party to come up with as many excuses as they can invent. This eventually turns into a Kafka-esque ping-pong game that can go for ten, fifteen years. OK, if one has money to go for fifteen years. But most artists, including myself, after four years, begin to rethink the idea of continuing. OK, I will go for ten years and will spend a minimum of $300,000, and, by miracle, will win the case. But what do I get? Nothing! Absolutely nothing! Harry Stendhal has no money. He owes money to too many other artists already. So he comes out the winner. He already got my money and he has already splurged it all. In short: a settlement for the artist means zero, and money lost on court case, while for the rogue gallerist it means he can go happily, as any predator does, looking for another victim.