- Ghosts of the Archive: A Review of Rosa Alcalá’s MyOther Tongue

- A Survivor’s Prayer: A Review of Ordinary Beast by Nicole Sealey

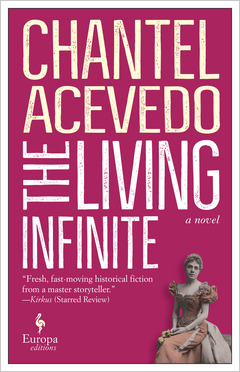

The Defiant Infanta: a review of Chantel Acevedo’s The Living Infinite

Melissa R. Sipin

In her fourth spellbinding novel, The Living Infinite, Chantel Acevedo has woven a narrative with a fierce main character who embodies what James Baldwin once said on the possibilities of “…moving beyond the Old World concepts of race and class and caste, to create, finally, what we must have had in mind when we first began speaking of the New World.”

Infanta Eulalia of Spain, the real, 19th-century princesa, is the inspiration for Acevedo’s expressive and rich novel. Eulalia once wrote a rebellious feminist memoir of her turbulent life, revealing the scandalous details of her mother’s affairs, Queen Isabella II, who was ousted from her reign when the infanta was four years old. But what is most revealing about her scathing memoir is how she reflects on the Old World’s transition into the New. She is a woman who lives beyond her caste, who creates bonds with those she shouldn’t; kisses her servants on the cheek as if they were familia, bending the societal and hierarchal rules that define her status and role in society. Throughout the novel, Eulalia’s audacity, her love for adventure, quick banter, and adoration for her dear friend and once milk brother, Tomás Aragón, become the center of this dizzying novel, which takes us from the glittering halls of the Palacio Real de Madrid to the bustling streets of Paris, Havana, New York, and Chicago.

What is so compelling about Acevedo’s fictional and historical tale is the deft and illuminating ways she paints the many lives of women who lived in a century that favored men and their escapades. The novel begins with a rejection letter from Pedro Medina, editor in chief of Ediciones Medina, in which he implores the infanta to trust the traditions of the Old World, as they are the only certainties they have. Acevedo then unfolds the story of Amalia, Tomás’ mother and Eulalia’s wet nurse, who is whisked away from the countryside of Burgos to the marbled hallways of the palace in Madrid. Throughout Eulalia’s and Tomás’ journeys, we meet strong-headed women—from the Queen of Spain, to the nursemaids and nannies who run the palace’s domestic sphere, to the talkative and spirited American, Eliza Jane, and Tomás’s first love, Juana, who dreamed to run a simple bookstore. The deep grief of losing infants, and the shadows they leave behind in a woman’s body and mind, is evident, marking how they behave and connect with each other for life and in death.

Eulalia grows into a fiery and brazen princess who defies what society expects of her, so much that one character observes: “I think that Eulalia, in writing this book, has shaken off duty. I think that because of it, she, at least, won’t be forgotten.” In the end, after the journey of trying to publish her scathing manuscript that further reveals how the nobility wasn’t noble at all— Eulalia confesses to Tomás that the freedom to speak, even if one must pay it in exile, is worth that price. Eulalia, whose name means, “well-spoken,” would rather live up to the meaning of her first name than be bonded by the traditions that ruled the Old World. Although Pedro Medina claims in his rejection letter that these traditions were the only certainties they had in a world rapidly changing, Eulalia’s journey of self-discovery and her fierce attachment to living with “true freedom,” regardless of race, class, and caste, manifests her as one of the harbingers of change and progress.

The Living Infinite illuminates the voices of women from a time when the Old World sifted into the New: when the darkness desperately needed lamps fueled by kerosene were replaced by the magic of the light bulb, and when the long days of traveling by carriage were replaced by the high velocity of trains. With elegance and poignancy, Avecedo threads into life the compelling story of Eulalia of Spain, a defiant princess who became a powerful manifestation of what it means to live beyond one’s caste, to disregard the chains placed down by tradition, and create a new woman no longer bound by duty. Like what Baldwin once about America and how its strength is in its possibility and potential to create a new human not tied to their place of birth, race, or class, Eulalia embodies this strength and rejects her crown. She creates new traditions, new certainties, new realities, as she speaks without fear and with real freedom.

Melissa R. Sipin teaches creative writing at the Oakland School for the Arts. She is published in Prairie Schooner, Guernica Magazine, and Salon, among others.