Grand Central Terminal in 1954.

In 1994, when I was Chief Curator for Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, I testified before the Commission on Chicago Landmarks in favor of protecting the 1951 Arts Club of Chicago designed by Mies van der Rohe. For my troubles I got called a carpetbagger in the city’s newspaper of record. Since then, I have come to realize that name-calling is standard practice in preservation “debates.”

I’ve been involved in a few other efforts to protect landmarks, but I don’t consider myself a preservationist. Why? Because the “ist” in preservationist implies an “ism,” an ideology. And the ideology of preservation—or how it is should operate in practice—is never very clear, at least not to me. Perhaps that is why name-calling is so prevalent as the typical preservation debate plays out like a media smackdown between private property owners and preservation activists, generating more heat than light.

Ill. 1. The home of Dr. Leonard Hochstein and Lisa Hochstein, built in 1925 by Walter C. DeGarmo.

The house (ill. 1) was designed by Walter C. DeGarmo, a prominent architect in Miami and Coral Gables. His buildings include the Woman’s Club of Coconut Grove, the 1907 Miami City Hall (demolished), and the Miami Beach Community Church. The Hochstein’s house is one of two DeGarmo residences remaining on Miami Beach. Of course, different people see different things in different ways, which is why landmarking is such a contentious issue. I can understand how admirers could see the house as DeGarmo’s “masterpiece.” But the Miami Design Preservation League’s distress rocket is a little over the top: “Its loss would be like knocking a tooth out of the Mona Lisa.”[1] (The Mona Lisa’s smile is not of the toothy variety, but never mind.)

Rather than focus on the critical issues involved, the media devoted space to gleefully referring to the owners—he a plastic surgeon, she a cast member of a reality show—as the “Boob God” (a description he apparently doesn’t object to) and the “Real Housewife.”

To me, there was a salient, needs-no-interpretation factoid that was largely ignored in the media tussle. DeGarmo’s masterpiece is four feet below sea level (for now). For obvious reasons, it would be illegal to build at that sea elevation today.

The Miami Beach City Commission voted unanimously against landmarking the house, but the League filed another lawsuit to hold up the Hochsteins’ permits for a new structure.

Ill. 2. Edward Durell Stone’s 2 Columbus Circle in New York City.

In 2002, the city allowed the Museum of Arts and Design to make a proposal for redeveloping the 12-story, 54,000-square foot building, which had been empty, or only partially used, for 20 years of its 38-year existence. Rather than demolish the building, architect Brad Cloepfil’s design maintained the building’s footprint and overall massing. (ill. 3) The street-level colonnade (and lollipop columns) would be replaced by a more welcoming and more spacious lobby. A new skin on the building would allow daylight into the galleries and public spaces, and enliven the largely blank façade. With respect to the new, more translucent skin, Cloepfil said, “We are trying to maintain its monumentality, but at the same time make it a more ephemeral body.” [2]

Ill. 3. Brad Cloepfil’s redesign of 2 Columbus Circle, now home to the Museum of Arts and Design.

In turn, a regular Times reporter on urban issues got up close and personal with Wolfe in yet another op-ed piece: “With its white, marble-clad façade on Venetian stilts, perforated by Pop Art circles, it is the anthropomorphic doppelgänger of Mr. Wolfe dolled up in his custom-made white suit, though the suit appears to patronize a better dry cleaner.”[4]

Herbert Muschamp, the Times architecture critic during this hoo-ha, threw everyone a curve ball when he weighed in on Stone’s design: The building “bore the personal imprint of [Hartford’s] taste. His taste was swanky. From the sleek wood paneling to the dark brass fixtures, the building at 2 Columbus Circle could have passed for the East Coast outpost of a private casino from the land of Mr. Lucky.”[5] Those words, it should be noted, were written in favor of preserving 2 Columbus Circle.

Muschamp’s was not the only unorthodox defense of 2 Columbus Circle. As noted by still another Times reporter: “Unlike preservation battles in which venerable landmarks are defended from replacement by mediocrities, this debate will concern functional improvements to a structure about which even admirers confess ambivalence, reaching for words like zany, whimsical, kitschy, kooky, and quirky to describe it.”[6]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission declined to landmark 2 Columbus Circle, and in 2008 the newly redesigned Museum of Arts and Design opened.

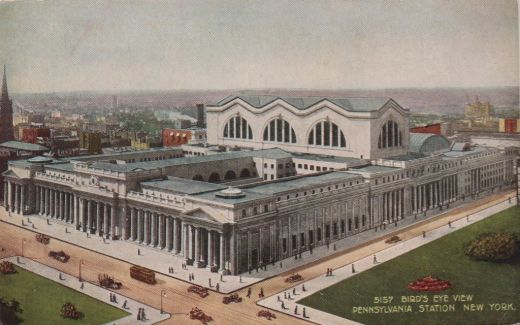

Ill. 4. New York’s Pennsylvania Station, built in 1910 by McKim, Mead & White, destroyed in 1963.

Ill. 5. “an introverted mash-up of Dunkin’ Donuts and Mad Men.”

Then, the corporate owners of Grand Central Terminal, one of the city’s grandest works of architecture, handed the preservation movement an incredible gift: a proposal to build a skyscraper above Warren & Wetmore’s 1913 Beaux-Arts masterpiece (ill. 6), with the columns of the new structure crashing through the vaulted expanse of the station’s great hall. What were they thinking? The fledgling Landmarks Commission tested its powers by propelling the issue into the courts. To many, the fact that New York state courts twice ruled largely in favor of the developers was no surprise. However, when the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1978, the Court innovatively ruled that it was constitutional for a city government to exercise “police power” to regulate historic structures in the same way that it regulates height, density, signage, land use, etc.

Ill. 6. Grand Central Terminal’s South Façade.

The writings of Ada Louise Huxtable, the first Times architecture critic, trace the arc of preservation’s path over the decades. Before its designation, Huxtable scolded the opponents of landmark protection for Grand Central: “One realizes, of course, that the city is broke; but one was not aware that this bankruptcy was moral as well as financial.”[7] But she took quite an opposite position on landmarking 2 Columbus Circle: “This small oddity of dubious architectural distinction, designed by Edward Durell Stone, has been elevated to masterpiece status and cosmic significance by a campaign to save its marginally important, mildly eccentric, and badly deteriorated façade—a campaign that has escalated into a win-at-any-cost-and-by-any-means vendetta in the name of ‘preservation.’ Never has that term been so taken in vain.” [8]

Ill. 7. Miami’s Freedom Tower, designed in 1925 by Schultze & Weaver.

Ill. 8. Hilario Candela’s 1963 Miami Marine Stadium, which was abandoned after Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

The Miami Herald Building, which was demolished in 2014.

The “equally unremarkable” Chicago Sun-Times Building.

Another growth industry for the preservation bureaucracy is the establishment of historic districts. As early as 1979, Miami Beach’s world-renowned Art Deco district was listed on the National Register of Historic Places—12 years before the city even had a preservation law. If there ever was a slam dunk for a historic district, the concentration of Art Deco hotels and other buildings in South Beach would have been it.

So I am sure I was not the only observer puzzled by the creation of the MiMo-Biscayne Boulevard Historic District, which stretches from NE 50th Street to NE 77th Street in Miami. I think the average citizen would understand the term historic district to mean an area populated with enough significant structures to be self-defining, like the Art Deco District or the French Quarter in New Orleans. Yet, in the Designation Report prepared for Miami’s Historic and Environmental Preservation Board, 50 of the 114 properties in the district—nearly half—are considered to be “not contributing” to the district’s supposed historic character. What’s more, many of the properties deemed “contributing” are highly questionable. One example will suffice. How does the truly ordinary, two-story former residence (ill. 11) at 7550 Biscayne, with its pitched roof, dormers, and brick chimney, contribute to a “Miami Modern” historic district? At best, only the very important Bacardi Building, the notable Vagabond Motel, the General Tire building, and the half dozen or so less important mid-century motels are individually worth considering for designation. That’s not a historic district.

A two-story building at 7550 Biscayne Boulevard, in Miami’s former MiMo Historic District.

Readers might ask, why are politicians comfortable with creating historic districts that include private homes, but apparently uncomfortable with designating private homes individually? My theory is that designating a district avoids the politically messy appearance of the government appearing to bully a single individual. Also, homeowners themselves often play a leading role in getting their neighborhoods landmarked.

Not surprisingly, the real estate industry is no fan of these historic districts. However, the emergence of community activists who are critical of landmark districts should be a wake-up call to preservationists. Daniel Kay Hertz, a graduate student at the University of Chicago and prolific blogger, [11] claims that recent districts have been designed to protect wealthier enclaves and that they make it virtually impossible to build anything in the city of Chicago but single-family houses—the most expensive and the least sustainable form of urban living. Hertz further argues that this proliferation of protected districts leads to a shortage of affordable housing.

While they dispute the community activists’ claims, the landmarking-advocacy group Preservation Chicago does not put itself in a good light when it offers the following advice: “There is a reputation of quality and real estate marketability that is achieved when an owner’s neighborhood is officially designated as a landmark.” [12] I think preservation groups should stay out of the “real estate marketability” business. Designating historic districts with the hopes that they might stimulate economic activity or boost property prices distorts the purpose of landmark laws and dilutes their legitimacy.

The proliferation of historic neighborhoods in Chicago wound up in court five years ago. The entire preservation establishment was severely shaken when a three-judge appeals court in Chicago not only ruled against a landmarks designation, but also declared critical elements of Chicago’s landmark ordinance were unconstitutional: “We believe the terms value, important, significant, and unique are vague, ambiguous, and overly broad.” [13] Indeed, those words can sound vague when preservationists try to apply them to properties whose value, importance, significance, and uniqueness are debatable.

Although the ruling was overturned on appeal, it is not difficult to imagine a more conservative court, possibly even the U.S. Supreme Court, agreeing with the three-judge panel. The Burger Court (the court that affirmed the landmarking of Grand Central Terminal) was infinitely more liberal than the Supreme Court of today, led by Chief Justice John Roberts. Would the Roberts Court accept arguments that preserving a building that is “zany, whimsical, kitschy, kooky, and quirky” [14] met the requirement of a compelling state interest? I even wonder how the Roberts Court—which believes corporations have the same rights as individuals—would handle the Grand Central case if it were before them now. I certainly wouldn’t bet money on a positive outcome.

So is there another way to protect important buildings, sites, and districts without all the name-calling? I doubt it, unless there are changes in the way landmarking works. In most cities, especially those that have already protected their most important buildings and districts, landmarking efforts often take place only after an owner has filed for a demolition or renovation permit, which triggers a landmarks review. An unexpected move to protect a previously unprotected property can leave owners feeling they have been blind-sided, if not spitting mad. You don’t have to be anti-preservation to feel that this sort of “last-minute landmarking” can be very unfair, even if it is legal.

I think there is a better way. Another “police power” the city wields is zoning. Since 1934, Miami has enacted various zoning ordinances, including Miami 21, which was adopted in 2010 after a long public process. The ordinance not only includes every property in the city, but is also accessible and understandable. Why not undertake a similar effort for historic preservation? The first step could be a series of charrettes throughout the city to solicit public and professional opinion about which properties should be included in the preservation code. No suggestion should be excluded. Then, promote a long discussion about where the bar should be set, in a thoughtful, rigorous way. Allow various groups to make comprehensive proposals for which properties do and do not meet a consistent threshold for landmarking, citywide. Submit the proposals to rigorous review by various professionals. Preservation experts with national experience could assess the proposals’ conformance with the “best practices” of preservation efforts across the country. Independent economists could undertake in-depth studies to evaluate the proposals in terms of their long-term effect on growth, tourism, affordable housing, real estate values, etc. Environmentalists could provide data on where preservation of historic structures makes the most sense, and where, in an era of rising sea levels, it does not.

As with Miami 21, due process would provide for public comment, revision, and modification of draft proposals. It would then be up to the City Commission to vote on the proposal that addresses the needs of the greatest number of competing interests. Once accepted, the preservation code would make it clear to all what is and what is not protected. Like the U.S. Census, regular updates could be made every 10 years. Discoveries, such as archeological sites, would be considered at the time they are made.

Or, maybe we should just leave things as they are? They say everybody loves a good fight. Perhaps even when it’s the same one—over and over and over again?

[1] David Smiley, “Dispute over Miami Housewife Lisa Hochstein’s Star Island Home Escalates,” Miami Herald, Posted on Dec. 20, 2012.

[2] David W. Dunlap, “A New Look for a 10-Story Oddity,” The New York Times, Published: April 1, 2003.

[3] Tom Wolfe, “The Building That Isn’t There,” The New York Times, Published: October 12, 2003.

[4] Anemona Hartocollis, “Preservationist Chic: What Would Tom Wolfe Do?” The New York Times, Published: July 4, 2004.

[5] Herbert Muschamp, “The Secret History of 2 Columbus Circle,” The New York Times, Published: January 8, 2006.

[6] op. cit. Dunlap

[7] Ada Louise Huxtable, “Landmarks are in trouble with the law,” The New York Times, Dec 22, 1974.

[8] Ada Louise Huxtable, Wall Street Journal, January 7, 2004.

[9] Christina Veiga, “City Commission staying out of Miami Beach historic-home dispute,” Miami Herald, posted on line 15 January 2014.

[10] Op. cit, Smiley

[11] Daniel Kay Hertz, “I Wonder Why We Have An Affordable Housing Shortage”, City Notes, Posted on July 22, 2014 (danielkayhertz.com).

[12] Preservation Chicago, 31 Landmarking FAQs, November 29, 2010.

[13] Hanna v. City of Chicago, Appellate Court of Illinois, First District, Fifth Division. Decided: March 6, 2009. (http://caselaw.findlaw.com/il-court-of-appeals/1036498.html#sthash.k4hs98r3.dpuf)

[14] op. cit. Dunlap