Cristina García Rodero: Rituales en Haití

Hunter Braithwaite

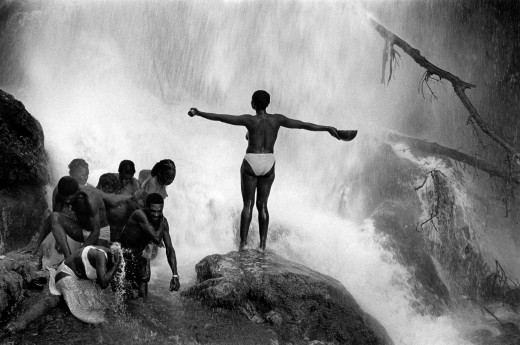

Cristina García Rodero, Hacia el sacrificio, Rituales en Haiti. © Cristina Garcia Rodero/MAGNUM PHOTOS

December 4, 2013 – March 29, 2014

Cristina García Rodero, a Magnum photographer and winner of the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund in 1989, is one of the great photojournalists—an artist/explorer who uses the camera’s democratic potential to reveal the hidden workings of the world, or to cast the visible in a new light. She has long been concerned with ritual, that physical manifestation of belief, and as such has documented many facets of contemporary spirituality, be it a body of work about Spanish cults, or one about Burning Man. For Rituales en Haití, she spent four years in Haiti, taking photo after photo after photo of the spiritual rites of everyday people. Though first and foremost a document of religious practice, these photos dovetail into discussions of colonialism and how “genuine” experience might be simultaneously curtailed by some rituals, and allowed for by others.

Haiti is part of the island of Hispaniola, where Columbus first landed in 1492, and likewise, these photos are all concerned with the meeting of two worlds—be it García Rodero herself, who ventured alone into the fervent core of the religious ceremonies, or be it the Haitian faith— a blend of African and Catholic rituals—or perhaps, most universally, the communion between the flesh and the spirit, between this world and the next. The photos here document Haitians with elevated spirits, their bodies and the environment interacting during a time when God’s presence is especially felt in both. And while the arrhythmic pulse of life and worship pounds beneath the photographic surface, an uncanny quiet defines the group as a whole.

Cristina García Rodero, Súplica a Ezili, Rituales en Haiti. © Cristina Garcia Rodero/MAGNUM PHOTOS

The water speaks to what Freud called the “oceanic feeling” of religion, being immersed in something more than yourself. With immersion comes relaxation. As such, many of the bodies are ungainly, and many of the photographs candid—not exploitative, but not necessarily reverent. They are religious without being chaste. In one of the Saut-d’Eau photos, a group of pilgrims stop rejoicing in the spirit long enough to concentrate on their own bodies. A woman tugs at a sagging breast. A man stares at his hands, completely oblivious to the fact that his shorts are pulled down, presenting a large penis. Elsewhere legs are jackknifed up, an ass or two given to the camera and the viewer. She depicts humans as those in possession of both souls and bodies. As the physical and the metaphysical levels of life complicate each other, viewers are forced to consider how they experience reality.

The exhibition is a detailed look at Haiti’s varieties of religious experience. Pilgrimages, animal sacrifices, the costumes of Carnival, little girls going to church. The most startling photographs depict human bodies writing in mud, resulting in a tableau out of Dante, or perhaps Hans Solo in carbonite. Caught in religious palpitations, they stare out, through the camera, through the viewer, focusing on the unseen. A goat about to be slaughtered has the same look in its eyes. There is brutality in these images. The viewer asks how on earth holy water can get so dirty. But perhaps what is most unsettling is how the prod the post-colonial heart, how they hint at the conflation between the tropical body and the tropical landscape. That, however, would be missing the point. The photos of the bodies in the mud evoke a type of inverted transcendence. Rather than the soul escaping upwards, it pulls the body to the earth.