Ruth & Marvin Sackner

Nathaniel Sandler

NATHANIEL SANDLER (RAIL): Let’s start with the name of the exhibition. Why A Human Document?

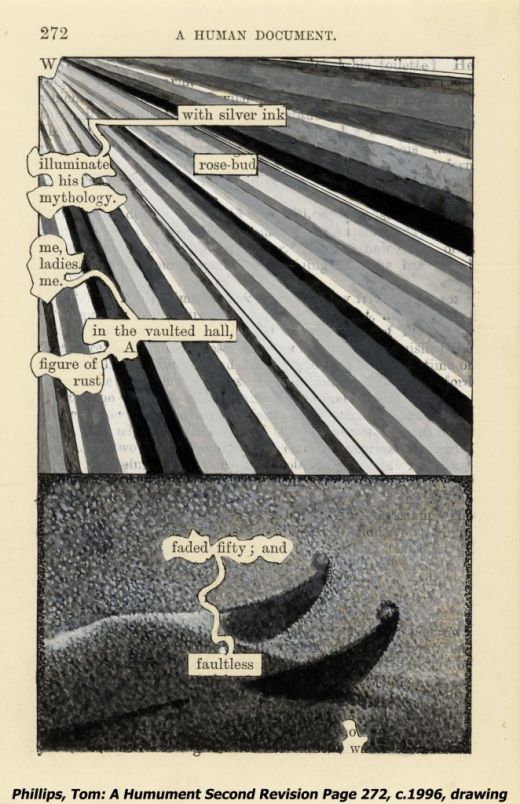

MARVIN SACKNER: That was chosen by the curator, Rene Morales. He chose the name A Human Document, which happens to be the book that Tom Phillips worked on, A Humement. He initially said it would be a selection from the Ruth and Marvin Sackner Collection of Concrete and Visual Poetry and we said, ‘OK, but it’s really the archive.’ And he replied, ‘OK, but nobody really knows what an archive is, so let’s make it a collection. Then apparently when he talked to people, everybody really knows it as the Sackner Archive, so he changed his mind.

RUTH SACKNER: I just want to add that Rene said he liked that it had the word human in it because it is a human collection, a personal collection, and not something done by an institution.

RAIL: How do you distinguish between a collection and an archive?

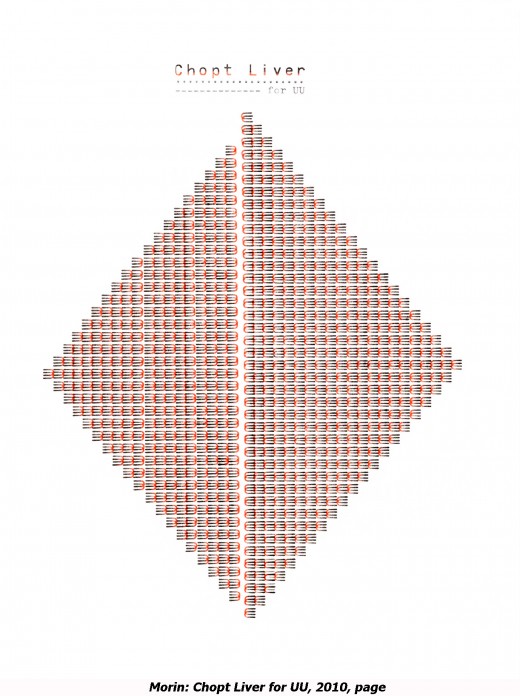

MARVIN: An archive is really a collection of various elements of an artist or a movement, so that it not only includes books and artwork, but also manuscript pages, ephemera, exhibition announcements, etc. This is really an archive of archives because there are around 200 artists’ and poets’ archives. That’s how we call our collection an archive. There’s also an archive of typewriter poetry and art, which we’re working on in terms of a book to be published by Thames & Hudson in 2015. And that’s an archive of a specific style of poetry and artwork. There’s calligraphy as well. There are many, many classifications as you consider an archive.

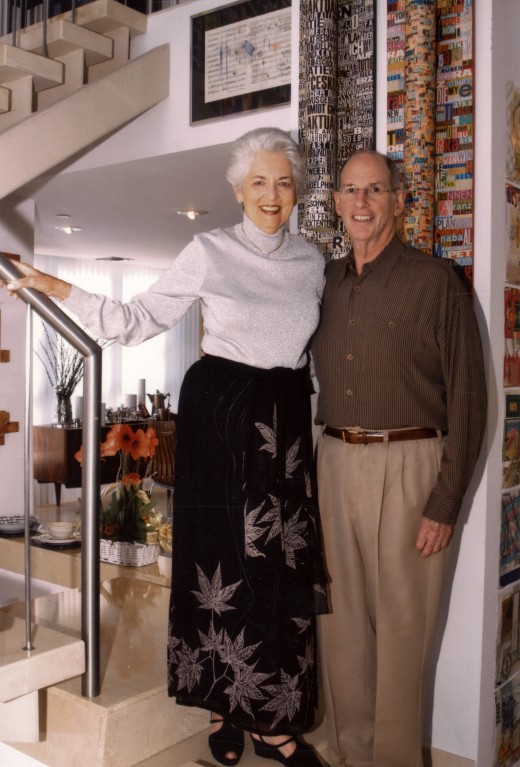

The Sackners in the Archive.

RAIL: Let’s circle back to Tom Phillips. I think his work and A Humument is a good introduction for a lot of people into the kind of work you’re caring for here. You have a lifelong relationship with him and you’ve been his largest patron. What is it about his work that initially attracted you and continues to attract you?

MARVIN: We first came across his work in 1974 in Basel, Switzerland. There was a retrospective of his work at the Kunsthalle. At the time in the Kunsthalle, and perhaps now though I’m not familiar, you could buy the works that were exhibited. There was a price list and you could go through it. When we saw the work, I knew the name Tom Phillips, but I didn’t really know his work. It’s the only exhibition we’ve ever been to where we went twice. We went the first day and spent several hours there. We went back the second day and spent several hours there. We knew that we wanted to start buying his work. We didn’t buy anything at the exhibition but the original A Humument was displayed between two glass frames, the original 320 pages and you could see it on either side. There was a price there. It was much too expensive for us, as we thought it would be. But we said we would love to buy this whole thing in the future. And we did. I paid it off over time, but we did buy it.

RUTH: I think the exhibition in Basel was the first time we saw work that visually was so captivating and also had the poems that he had discovered in the text. To me it was an eye opener that you could combine these two elements in a work of art. We have a lot of stories where people have the same reaction. One of the people who came here said ‘I am going to go home and tell my son that I saw this work with poetry and beautiful drawings and engravings, because his art teacher told him when he put letters and words in his paintings ‘No no no, you can’t do that, that’s not art.’

MARVIN: On the other hand, as Tom points out you can go back to the early Dutch paintings and so forth and find words at the bottom.

RAIL: In Asian art the tradition is longer.

MARVIN: Even more so, that’s right.

RAIL: With a lot of these works in your archive, the book is sort of transformed. I know artists’ books, such as Didier Mutel, are a part of the collection as well. Where are we going with the future of the book? It’s obvious we don’t need 50 million copies of The Da Vinci Code, but these very small run hand-crafted books, single edition art objects, are a possible avenue that the book can go.

MARVIN: That was really a side venture for us because when we first started the Concrete and Visual Poetry Archive we didn’t know anything about artists’ books, in terms of unique books. The collection started in 1979 as a deliberate attempt, although we were collecting works by Tom in 1974 and other artists that visual verbal imagery. We were also collecting Constructivism. It was a mishmash of various things. But then, in 1979 when we came across Emmett Williams’ Anthology of Concrete Poetry that set the goal right then and there. We realized that we could have a collection that was unrivaled because nobody was collecting it. We liked it and at the time we didn’t even know there was a word concrete poetry. We were very strict about this. We would only buy concrete or visual poetry books or critiques or anthologies. We didn’t think about Artists’ books.

RUTH: One of the artists’ books that will be in the PAMM show is a Sandra Jackman piece. We were in Los Angeles, and we picked up a book of hers and looked at it. An artists’ book was so new to us. And we just loved it.

MARVIN: And it was not really concrete poetry. So even though we call it the Concrete and Visual Poetry Archive, it really is a word-image collection. That’s what it is.

RUTH: We did make the definition that the artists’ books would have to have some sort of experimental text and be integrated into the image. It couldn’t be just an illustrated book.

RAIL: I like that. It’s interesting that you use word-image collection and not word-image archive.

MARVIN: Word-image collection is just a style and the archive implies all the documents that surround it.

RUTH: You could say that the archive includes many collections.

RAIL: This collection and the process of collecting itself is an important part of your lives, your relationship to one another and your relationship to the world. I have always seen collecting as an extension of identity. How much of yourselves do you see in your own collection?

RUTH: A lot. And a lot of togetherness. Luckily we have the same tastes and we’ve been doing this together since the very beginning. I remember I wanted a color field painting. I loved Diebenkorn. I saw a beautiful Friedel Dzubas and we put it on our walls. I found within a couple years that I wasn’t excited by it and there wasn’t enough to keep me interested. It now hangs in the director’s office at the Lowe Art Museum and he loves it (Ed. note: it no longer hangs there but it is in their collection).

MARVIN: I can tell you, there are a lot of people that come here and get very nervous. And I’m talking about directors and curators because they think they know everything. And they come here and they know nothing. And they get very upset. We’ve had people run out of here.

RUTH: You’d be surprised how many people have learned from going to the Fluxus Museum and exhibitions. The music, poetry and their performance has caught on. We sort of laugh that our very poorly known and poor artists are being rediscovered all the time from the ‘60s and ‘70s.

MARVIN: In 1979 we were buying things from a bookstore in New York called Bound and Unbound. They gave us an invitation to go to a Fluxus dinner on a pier in the East River. On this pier there was a very long table with white tablecloths, silverware, crystal, etc. There were two people there who happened to be the Silvermans. Gilbert and Lila Silverman from Detroit, who donated their Fluxus collection to the Museum of Modern Art. We didn’t know them, but we started talking and talking and talking and talking and talk- ing. And then we realized we were the only people there.

RUTH: Nobody else was invited.

MARVIN: That was the Fluxus dinner. So we went out to get something to eat and became good friends afterward.

RAIL: This image of directors and curators being intimidated by the collection is too good to let you slip right by it. There’s a lot of emphasis being placed on curation and the importance and the role of the curator as an arbiter of knowledge in the art world now. But you guys do not come from an art historical background.

MARVIN: Not at all. Zero.

RAIL: You’re not dissecting the work in that way. Although you want other people to, you’re not doing it yourselves. I think that’s incredibly refreshing. What do you think about being an outsider to the art historical narrative?

MARVIN: Well, I have written essays for art books. Ruth will tell you what she thinks about those essays.

RUTH: Well the first time I read one of his essays, it was very clearly written and I understood everything. So I said, ‘but Marvin this sounds like a doctor writing about art. And he said, but I am a doctor writing about art!’ But the thing is, we’re really not intimidated by these scholarly people, even though some of them can be very intimidating.

MARVIN: One of the things I have is a major visual memory and most people don’t have the capability to remember the 75,000 works in the collection. And we don’t have a curator. I can’t name a collector with this many items that have catalogued it themselves. This is a little bit different than most collections. There are people that collect big paintings. If you have 300 big paintings you have a big collection. But to have all these little magazines, small press stuff and obscure stuff, to have this massive amount of material without a curator, I don’t think there’s anyone else.

RAIL: Why have you stayed away from having a curator?

MARVIN: Well we did have one. And it didn’t work out. If you have an ego, which I do have, and the collection is going on the Internet, I want to get it right. That forces you to look at things. That’s why I am knowledgeable about this collection. I’ve catalogued it. I know it. If I had given it to someone else I myself wouldn’t have the slightest clue what’s going on.

RAIL: That’s an interesting point. You’ve catalogued it yourself. And it becomes much more personal. It’s you molding it, it’s you picking and choosing what goes and what stays.

MARVIN: And what it means.

RUTH: And what things are related to each other

MARVIN: For example in the book we’re writing now The Art of Typewriting, it would be very easy to list artist, artist, artist, artist, artist, but that would be relatively dull I think. It would be more academic. So I asked the editor if I could write anecdotal stuff, and he said yes. I said, I think it would be more interesting if I lined it by styles of typewriting, because it’s more interesting to see how one artist handled this topic versus the other. They’re willing to let me do anything, really, but they want pictures; that’s the name of the game. This book could be 600 images when they get finished with it.

RAIL: For that kind of book, you’re already looking at text, so they don’t want to pile on. And it’s the same approach you guys take. They don’t want it to be bogged down in academic artspeak. They want it to be accessible. I think it’s admirable that you become the experts even though it was never your intention.

MARVIN: What we wanted to do in terms of collecting, our ambitions were great, we wanted to collect everything. But you can’t. We also went down a lot of side paths: language art, language poetry. It will be an evolving collection. And people ask where’s it going to go, what’s it going to be. And we’re getting up there now. I know all about this collection and most people would look at some of this stuff and not have a clue. Even if they had the database they wouldn’t know how to look at it. I should be involved if it goes some place for a couple of years. When asked where I want it to go, I want it in Miami. There have been talks going on among the museums and libraries here about sharing it, because this collection will not go to a single library or a single museum, it has to go to a library and a museum because of the material. The second place, if it can’t be here, I’d like it at the University of Pennsylvania. And if that doesn’t happen we’re probably going to have to break the collection up and sell individual archives. The asking price is around 20% of fair market price and the rest will be donated.

RUTH: Plus the fact that institutions will value it more if they pay for it.

MARVIN: I want it to be accessible. I don’t want it to be thrown into a basement. Wherever it goes, if it goes in one body, the collection will grow by itself because artists and poets will just donate to it. I get donations all the time from people who want to be a part of it. I tell them, I’m a collector not an institution. They still want to be here.