Juan Downey, Video Trans Americas, 1973–76. Fourteen-channel black-and-white video, with sound, and vinyl map, dimensions and duration variable. Installation view: Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2015–16. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of the Latin American and Caribbean Fund and Baryn Futa in honor of Barbara London. © 2016 Estate of Juan Downey and Marilys B. Downey. Image © The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Thomas Griesel

Juan Downey, Video Trans Americas, 1973–76. Fourteen-channel black-and-white video, with sound, and vinyl map, dimensions and duration variable. Installation view: Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2015–16. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of the Latin American and Caribbean Fund and Baryn Futa in honor of Barbara London. © 2016 Estate of Juan Downey and Marilys B. Downey. Image © The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Thomas Griesel

Juan Downey, Yanomami jugando con CCTV, 1976–77. Courtesy the Estate of Juan Downey and Marilys B. Downey

Born in Santiago in 1940, Downey was an early adopter of video as an art medium and a proponent of cybernetic utopianism, optimistic that technology could expand the senses and connect individuals. His seminal installation Video Trans Americas was created between 1973 and 1976 using a Portapak, the first video camera that could leave the studio. The Portapak gave artists of Downey’s generation mobility. Since each second of footage was less precious than that filmed with celluloid, early video work tended to push durational boundaries, as well.

Video Trans Americas condenses several years of black-and-white video travelogues, mostly filmed in (and with) indigenous and working-class communities throughout South and Central America, into a fourteen-channel video installation. On view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), in their recent exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980, the videos are bound together within the installation by an outline of the Americas stretching contiguously from the walls to the floor.

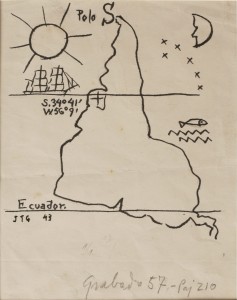

Downey’s graphic outline of the continent brings to mind América Invertida, Joaquín Torres García’s small, but iconic ink drawing from 1943, which was simultaneously on view at MoMA. Torres García flips South America’s cone to the top of our frame of reference, a reorientation that feels physically manifested as the viewer moves through Downey’s installation.

Footage, including of street protests in Cuzco, Peru; the ruins of Machu Picchu; weavers in Chiloé, Chile; and a Texas blues singer, play on pairs of cube monitors encased in black plinths. These are placed throughout the space so that, when walking between the monitors, one might simultaneously cross the Amazon, pass over the Caribbean, and come to rest somewhere over New England. The installation places disparate individuals and remote communities within walking distance of one another on a stateless continental mass.

Transmissions focused on conceptual and political artistic practices during the Cold War, and Video Trans Americas was instigated in part by the 1973 coup d’etat in Chile. The installation was produced amid this climate of social movements against authoritarianism throughout the continent, and Downey trained his camera on marginalized communities, putting the Portapak’s potential as a tool for cybernetic utopia into practice. The portable video camera allowed for instantaneous playback, and Downey employed both technological and cultural feedback in his process. He recorded documentary-style footage while on the road, which he watched with his subjects on-site, using live feed, and screened again to people he met in other places, connecting previously unlinked communities in a sort of analogue precursor to web 2.0.

In his drawings, sculptures, and writing from this time, Downey considers the cyborg, a futuristic man-and-machine hybrid, saying “technology operating in synchronicity with our nervous systems is the alternative to a disoriented humanity.” Are we these cyborgs, our movement through the world, mediated by our tiny screens? If so, this utopian view of hyper-connectedness, technology as an extension of the senses, is questionable. However, nearly two decades before the Internet was available to civilians, Downey encouraged interaction by shooting with his subjects, putting the camera in their hands and letting their eyes guide the lens, and using simultaneous playback as he filmed.

Joaquín Torres García, América Invertida (Inverted America), 1943. Ink on paper, 22 x 16 cm. Museo Torres García, Montevideo © 2016 Sucesión Joaquín Torres García, Montevideo

In Video Trans Americas and other video works he made during this time, Downey maintains both a technological self-awareness and an awareness of the social orientation of his work. These concerns are equally apparent in The Laughing Alligator, which was screened at Artists Space Books & Talks in New York this past December. It is a half-hour single-channel narrative video shot during the eight months that Downey, with his wife Marilys and stepdaughter Titi, lived in the Amazon with a small community of Yanomamo.

In the mid-1970s, when Downey filmed The Laughing Alligator, the Yanomamo lived in villages of about five hundred people, moving every few years when the soil that nourished their banana and yam fields began to be depleted. The village Downey and his family lived in consisted of a communal roof around a central plaza of flattened earth, with sleeping hammocks hung from the rafters. Toward the beginning of the film, Downey is being led through the forest to the village. There is an implied showdown between Downey with his camera and the Yanomamo man who is leading the expedition, who springs from the brush with his rifle pointed at the artist.

This shot-reverse-shot editing, with Downey narrating the encounter in voice-over, explicitly refers to the reigning anthropological treatise on the Yanomamo at the time, Napoleon Chagnon’s The Ax Fight. Chagnon referred to the Yanomomo as “the fierce people,” supposing a deep-seated cultural propensity for violence and warfare. The Ax Fight literally focuses on a single event—an ax fight between two individuals that draws a sizable crowd—and positions this violence at the center of the community, the bare dirt plaza, and at the center of Yanomamo culture.

Downey blithely mirrors this self vs. other posturing in the shot-reverse-shot structure of his showdown scene. However, the ruse is quickly up. A flash of humor crosses the gunman’s face, his eyes relax, he grins, and lets out a belly laugh. This looped gaze, where the camera is both observing and being observed, is sustained throughout the film, whether Downey is behind the camera or in front of it, whether it is his gaze or the camera is being operated by a local person filming his or her own home. It is this sensitivity, this empathy that is so apparent in the act of looking and being looked at with curiosity and openness, that interests me.

The camera is a tool for documenting the world, and the impulse to take it to exotic places has been strong since the advent of recording technology. The artist’s way of looking through the lens, the style of observation, the type of attention that is given to that which is being filmed, something akin to empathy, is another kind of tool.

What happens when empathy guides the way we look through the lens? And how does it work when the camera is pointed not at other people, but at other forms of life, the minutest beings that make up our world? How can I access not just the exterior, the surface, but the inner life of the species on the other side of my lens? These questions were on my mind as I packed my studio gear for Tierra del Fuego, intending to film lichens that have been clinging to the same rocks since before Darwin passed through in the Beagle Channel.

I have extended my trip an extra month to join an expedition of Wildlife Conservation Society scientists who will survey a colony of elephant seals in the Admiralty Sound at Karukinka Natural Park—just beyond the point where the Pan-American Highway dead ends into the Patagonian Sea. There, in support of marine conservation, marine biologists and veterinarians will construct a curious cybernetic assemblage. Satellite transponders will be affixed to the heads of the seals with epoxy, so that as the animals migrate around Cape Horn, their route can be plotted, a highly technological form of interspecies communication.

At the end of the Austral summer, the elephant seals will return from Chile to Argentina, crossing historically fraught national borders via the treacherous southern seas. In doing so, they will show us an image of their own world, the boundaries of land and sea that sustain their lives, that have scientific and political value in the field of marine conservation. This human-animal collaboration will create an extra-continental map of the Americas. For my part, Downey’s connected gaze, and the idea that technology gives us access to a world beyond our own senses, will be a starting point as I train my lens on these other lives and spend ten days living in their world.

Christy Gast is an artist whose work across mediums reflects her interest in issues of economics and the environment.