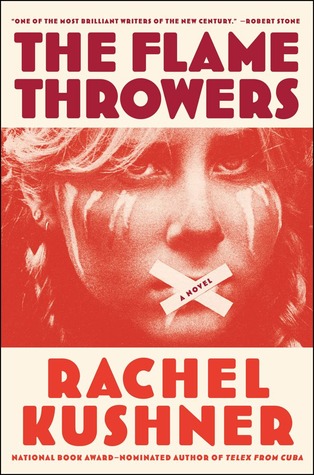

The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner

Arlo Haskell

Scribner, April 2013

Like Telex, Kushner’s Flamethrowers is a richly imagined novel set in a historic period marked by violent popular revolution. Telex sprung from the momentous events of Fidel Castroʼs successful guerilla campaign and rise to power in Cuba; in Flamethrowers the backdrop belongs to the Italian labor activists-slash-terrorists known as the Red Brigades and their anarchist American peers, Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers, who blurred conceptual art with violent actions intended to foment revolution on Manhattanʼs Lower East Side. Like the Occupy protests that were underway as Kushner was writing this novel, the Brigades and the Motherfuckers are united by a Robin Hood ethos of wealth redistribution and by the fact that—as popular movements—they ultimately fell short of the radical structural change they sought.

As a novelist, Kushner is fascinated by potential, by what might happen, or—even more tantalizingly for the student of history—what might have happened, what almost happened, and what could have happened if circumstances had been different. In Reno she has given us a central character who is “made to burn,” as the epigraph puts it, a speed-obsessed young woman who pivots from the art world to armed revolution by way of a love affair gone bad, who will not waste time on an intractable problem before moving on to the next question.

Reno’s tool as an artist is the motorcycle. Her medium is speed, and the ground upon which she acts is time itself. “You wanted to be traceless,” Reno remarks of her goal on the motorcycle, and at great velocities she approaches this ideal. “Racing was drawing in time,” she says, leaving “a high and graceful line, with no sudden swerves or shuddering edges.” As the speedometer tops 100, time seems to stand still as speed delivers Reno into “an acute case of the present tense.”

Time for Reno is both a surface to be acted upon and an enemy to conquer. “A woman so young, with no detectable pedigree or accomplishment,” Reno knows that her access to the New York art world rests entirely upon the “young electricity” that impels successful men toward her magnetically. She is conscious of the tentative and temporary nature of this appeal, noting of another woman: “She was beautiful, it was true. But I had seen, that night I met her, that her beauty was going to leave her like it does all women. For the face, time relays some essential message, and time is the message. It takes things away.”

In a recent issue of The Paris Review, Kushner touches upon the contradictory nature of The Flamethrowers, “in which the female narrator, who has the last word, and technically all words, is nevertheless continually overrun, effaced, and silenced by the very masculine world of the novel she inhabits.” The book teems with motorcycles, guns, and stupendous explosions. It is stuffed with misogynist cruelties: a driver sprays his girlfriend with gasoline at a rest stop, then throws lit matches at her feet; a photographer encourages women to slap and punch themselves in the face, then pose for the portraits that will fill his upcoming show. But the most unsettling contradiction in Kushner’s novel is that women—desperate for authenticity and autonomy—are complicit, and occasionally enthusiastic, in inviting carnage into their own lives. Reno reports on these abuses dispassionately, but with a twist, reminding us that “certain acts, even as they are real, are also merely gestures.”

As Reno seeks to inhabit a hostile world while at the same time defending herself from it, the gesture and the real will become inextricably intertwined. Kushner alludes to this risk in “Lipstick Traces,” her recent review of Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispectorʼs work, writing: “Femininity… is both utterly natural and completely fake, a kind of psychosis, and also the unifying impression a woman makes, the thing that keeps her gathered.”

Reno ultimately realizes her own potential and capacity to act, and as she breaks through stasis she sees that time need not be the enemy of youth, nor youthfulness a woman’s only asset. “I wasn’t in that kind of time, curler time,” she remembers, flashing back to a scene from a film that haunts her, where a woman in curlers waits for something that never happens. Times change, and the men Reno leaves in her wake know this as well. “As you get older,” the father of Reno’s lover Sandro, instructs, “you tolerate less and less well women your own age… I used to think it was because I’d escaped time and women didn’t. But that’s not the reason. It’s because I’m stunted. Many men are. If you are that kind of man when you grow up, Sandro, you’ll understand. You’ll go younger in order to tolerate yourself.”