- Barnacles on the Boat: Notions of Literature at the Key West Literary Seminar

- Public Art In Miami: PortMiami and Beyond

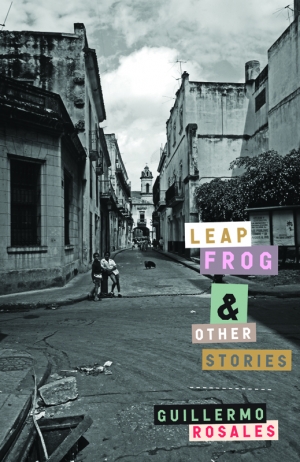

Leapfrog and Other Stories

P. Scott Cunningham

El Juego de la Viola has been rendered by Kushner into Leapfrog—a flowing and graceful Spanish phrase appropriately wedged into an Anglo-Saxon spondee. (The difference tells you everything you need to know about the art of Spanish-to-English translation.) But it’s worth noting that El Juego de la Viola had already been published in the United States—in 1994 by Miami publishing house Ediciones Universal, which tells you everything you need to know about Miami’s relation to the rest of the United States. Until very recently, Universal had a wonderful bookstore, too, on Calle Ocho. When people talk about Miami not being a literary city, I often think of Universal, and how much the employees at New Directions would probably love to have that kind of tunnel into Latin American literature in their neighborhood.

On the other hand, the vast majority of Miamians, especially native English speakers, probably never set foot into Universal, and not very many people are nostalgic for it now. Miami’s great weakness is its lack of self-nostalgia. We’re plenty nostalgic, but only for other places: Cuba, New York, Venezuela, etc. And yet, on our very streets, Guillermo Rosales went out for coffee, smoked cigarettes, wrote epic poems, and burned all of it, probably in one of our wonderfully mislaid fireplaces with parrots carved into its stone. He might have bought one of those fake logs at Publix to do it. His bag boy at Publix might have even been the great Cuban poet Lorenzo García Vega, who hated Miami so much he renamed it Albino Beach.

Rosales hated both Miami and Cuba equally, an inconvenient political position for an exile community dreaming of a return. In Rosales’s other surviving work, The Halfway House (also published by New Directions and translated by Kushner), William Figueras arrives in Miami and is almost immediately abandoned by his relatives, who were expecting a polished literary gentleman. The youthful protagonist of Leapfrog, Agar, hides from family and friends alike, declaring to himself, “You really were happy alone.” Rosales and all of his simulacrums know they are disappointments to the world, and that the world, no matter its political affiliation, will find ways to oppress the weak.

In this way, Rosales has much in common with the tradition of noir. Figueras feels infected by the brutality he witnessed and contributed to in Cuba the same way Robert Mitchum feels comprised by his past life in Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1942). One of the stories in Leapfrog is subtitled, “Taking license with Ray Bradbury,” and we know that Rosales worshipped Hemingway and Faulkner and went to as many as movies as he could. It’s not hard to imagine him sitting rapt beneath Anthony Mann’s “Raw Deal” (1948), Nicholas Ray’s “In a Lonely Place” (1950), or Samuel Fuller’s “Shock Corridor” (1963) and seeing correlations between their fated protagonists and his life inside of an oppressive dictatorship.

But like in noir, there’s no border to that oppression. Its victims and perpetrators carry it inside their bodies. In “An Axe to the Sideburns,” a Miami barber shaves the neck of the man who murdered his son in Havana thirty years ago. As you might imagine, the man’s revenge fantasy doesn’t play out as scripted. In another revenge fantasy—perhaps the most popular revenge fantasy in the history of Miami—a man is given the perfect opportunity to assassinate Fidel Castro (who has been re-named “Cornelio Rojas”). The man is himself a murderer. He accidentally killed his aunt trying to rob her hidden roll of bills in order to pay a ferryman to take him to Miami. Out of his desire for exile, he is given the opportunity to free the whole country, but the man who gives him this opportunity, Mr. Coro, is himself a would-be dictator. He hates Rojas not because of what he’s done to the country, but because Coro feels he should have been the one to become dictator. Rosales, like a good noir director, makes you feel like everyone is complicit in the violence of the world, and the only true exile is death.

In the forward to Leapfrog, Norberto Fuentes calls Rosales’s literary self-immolation “an act of courage” in the face of a Cuban exile community that “doesn’t understand him” and “can’t stand him.” Now that Rosales has been translated into English, he can probably add the rest of Miami to that list.