John Opera, Equivalent Simulation

Hunter Braithwaite

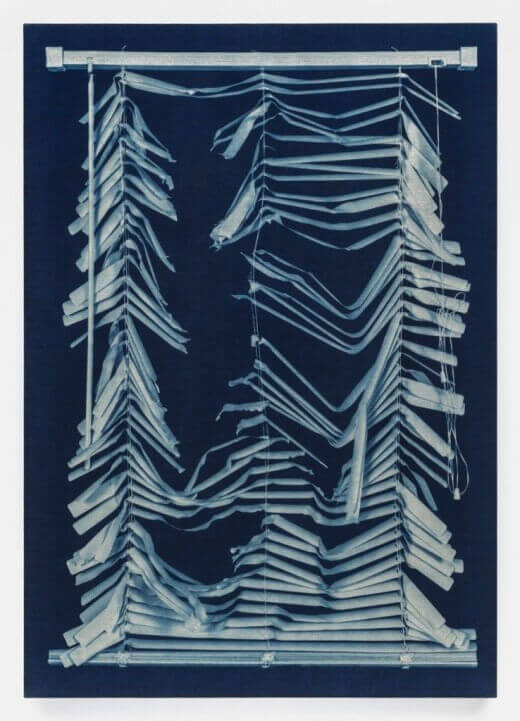

John Opera, Blinds II, 2014. Cyanotype on linen. 48 x 34 inches

March 22 – May 17, 2014

I’ll never think about photography without thinking about liquid. Not the pungent smell of developer (although I do think of that a lot, about how an image rises from the pool like Ophelia). I think of a sentence written in 1977. Susan Sontag said that “precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” I can’t get enough of those words, of the mixed metaphor, of the image of the argument itself, and of the surrounding disintegration that it implies. No matter how crisp and delineated a photograph might be, all it does is point to nature and time fleeing, evaporating, dripping away.

These cyanotypes by John Opera are smart. They cover all their bases. The relationship between window/lens and scene beyond is addressed, as is the codependency of the image and the frame. The exhibition proceeds like an indigo essay, securely scaffolded and footnoted. Like something deeply considered before the act of writing.

The title of the show refers first to Alfred Stieglitz, whose Equivalents photographs of clouds and skies are some of the most elegant images ever pulled dripping from the stop bath, and then to Baudrillard, whose Simulacra and Simulation has had generations of students and stoners asking each other what’s real, no I mean like, what’s really real?

John Opera, Equivalent 02, 2014. Cyanotype on linen in artist’s frame. 33 x 26 inches.

The outside world is reproduced with a bit more fidelity in the Sun Sky series. For these, Opera mounted a cardboard telescopic pinhole lens onto the body of a digital camera and took photographs of the sun from his front porch. When the photosensitive linen was exposed by the sun, it formed a closed circuit between subject matter, process, and art object. And while this is ontologically fascinating, it feels a bit too…ontological, as if the photographs weren’t taken on the porch, but in a classroom.

John Opera, Sun Sky 1, 2014. Cyanotype on linen in artist’s frame. 26.5 x 21.5 inches

The three-dimensional space implied in all of the photos is carried over to the frames, which are wrapped with yet another series of cyanotypes. These frames behave as they should—framing the image—but then one looks up to see that he’s used the same technique to cover two-by-fours at the top of one of the gallery walls, a gambit which frames the entire exhibition, (as well as the gallery’s clerestory window). I suppose this suggests a larger metaphor for the relationship between photography and the world (and, from my own experience, between art writing and art.) That is, there is always more outside the frame, but there are always other frames.