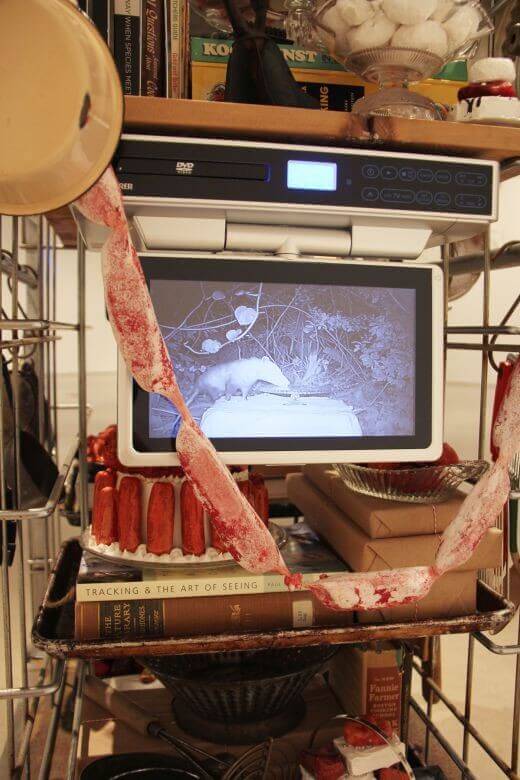

Dana Sherwood, Banquets in the Dark Wilderness, 2014 (detail). Videos, monitors, plaster, clay, varnish, steel baking rack, books, glassware, aluminum, enamel cooking implements, and sausage casings, 36 x 49 x 60 in. Courtesy Blueshift Project

February 12–March 26, 2015

In the Blueshift Project’s brochure for Made in New York, a group show featuring eight New York artists and curated by Robert Dimin, an effort is made to express that the works on view are separate from the “noise” that results from the contemporary art fairs that swarm Miami each December. I visited the gallery on a quiet day soon after the show’s opening and was led through it by co-director Sofia Bastidas and manager Ana Clara Silva. Each had interesting insights to share about the overall concept of the grouping, which brings together many works that address the human and animal body and–—although made in New York—issues close to home in Miami.

David Brooks’s marble animals are made of geometric blocks assembled to approximate the shape of animals on the verge of extinction; the forms are abstract, but their weights are not—each corresponds to the average weight of the actual animal, such as the 218-pound Sumatran Orangutan. The shipping crates that the works travel in are also on view and feature stenciled representations of the animals that can be found inside. These crates are functional and bear the markings of their travel.

Dana Sherwood’s animals can be found on hidden camera, enjoying the spoils of opulent feasts the artist set out in the wild. Motion cameras pick up raccoons, vultures, and possums feasting, most often at night, on Sherwood’s elegantly plated meals, complete with white tablecloths. Surrounding the video monitors are the implements she used to make the food, including utensils, vintage cookbooks, and representations of the food itself made of a kind of (homemade) Play-doh.

Imagined bodies of both animal and human form come together in Jen Catron and Paul Outlaw’s Goya Attempts to Teach the Masses Using Goats as Visual Aids (2012), which replaces the pastel horses found on a child’s merry-go-round with tattered taxidermied goats, who will bleat plaintively in a circle if you add twenty-five cents to the machine. The result is comical—some of the goats, though ragged, sport overdyed wigs and bling—but it’s a ride you’d never like your child to scramble onto.

Other works—Brooks’s towering cherry pickers that resemble dystopian palm trees, Caitlin Cherry’s pool that appears at once opulent and denigrative (no diving in this shallow replica of suburban comfort)—might strike a chord with those in Miami and New York who maintain a nagging anxiety about the continuous high-end, high-volume development of cities built on water.