Măiastra: a history of Romanian Sculpture in twenty-four parts

Dr. Igor Gyalakuthy

“Hard as I try, it is impossible for me to separate in my mind the memory of that strange week from the image of the gravity-slurping steel behemoth that is Vera Mukhina’s worker and kolkhoz woman.”

—VDNKh, formerly VSKhV or VCC, in English the “Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy,” Moscow, Russia, 1972

I must have looked absurd in its contrast: lean as a rod with patchwork facial hair and a sweep of greased hair falling in my eye, dressed in a ratty beige sports coat and brown wool trousers. I had only been a professor for a few years when I was invited by the Russian government to present a lecture on Romanian sculpture, and to participate in a panel discussion on the state of Soviet Art as it existed in the various loose appendages of the Socialist Republic.

My colleagues on the dais were art historians from Belarus, the Ukraine and the former Yugoslavia, among others, and I confess that comparing notes with these superior minds was a joy. As a fledgling scholar eager to have his work published, I had written on Socialist Realism in Romania and the Balkans. I was moderately well informed on my subject, but my opinions on the Romanian work that sprang from it were far from glowing, and it soon became clear to me that though my handlers regarded me as an “expert” in the eld, none of them had bothered to read my writings. [Note: some of it, I confess, understandably.]

In the shadow of Mukhina’s dubious masterpiece, I felt a sense of dread about the lecture I was preparing to deliver. I was humbled by the depth of feeling that stirred in the breast of the woman who had sculpted it, and by the park in general, which is larger in square footage than the principality of Monaco. In comparison, my talk seemed small and petty, tainted as it was by the superficiality of the feeling I had for it all.

I decided instead to tell the story of Dumitru Demu, a Romanian sculptor whose sad tale has made him, at least in the tiny solar system of our plastic arts academia, a sort of folk hero, or villain, depending on whom you ask. It was my feeling that this story, more than any off-handed jibe I would land about the formal qualities of Socialist Realist work, could best shed light on the experience of making art under Communism.

This is the story I related.

Dumitru Demu, or Dimitri or Dimitrios Demou, came from a family of Aromanians who emigrated from Macedonia to Bucharest when Dumitru was young. Talented from an early age, he studied at the School of Fine Art in Romania where he showed an aptitude, if not exactly a passion, for sculpture.

One day a Russian man came to young Demu’s studio in Bucharest. With him he brought an offer: sculpt the busts of Communist leaders for Romanian civic centers, beginning with Marx and Lenin, and spreading to political figures across the party. Demu was promised a fortune for the thousands upon thousands of busts that would be made from his models. The naïve, hungry artist agreed, despite the anti-Communist politics of his parents and, indeed, himself. Sometime after, the man returned to Demu’s studio. The Russians had begun trading busts for Romanian wheat and oil, the man told the young sculptor, so his talents would no longer be required. The busts the Russians had been importing into Romania looked suspiciously like his own.

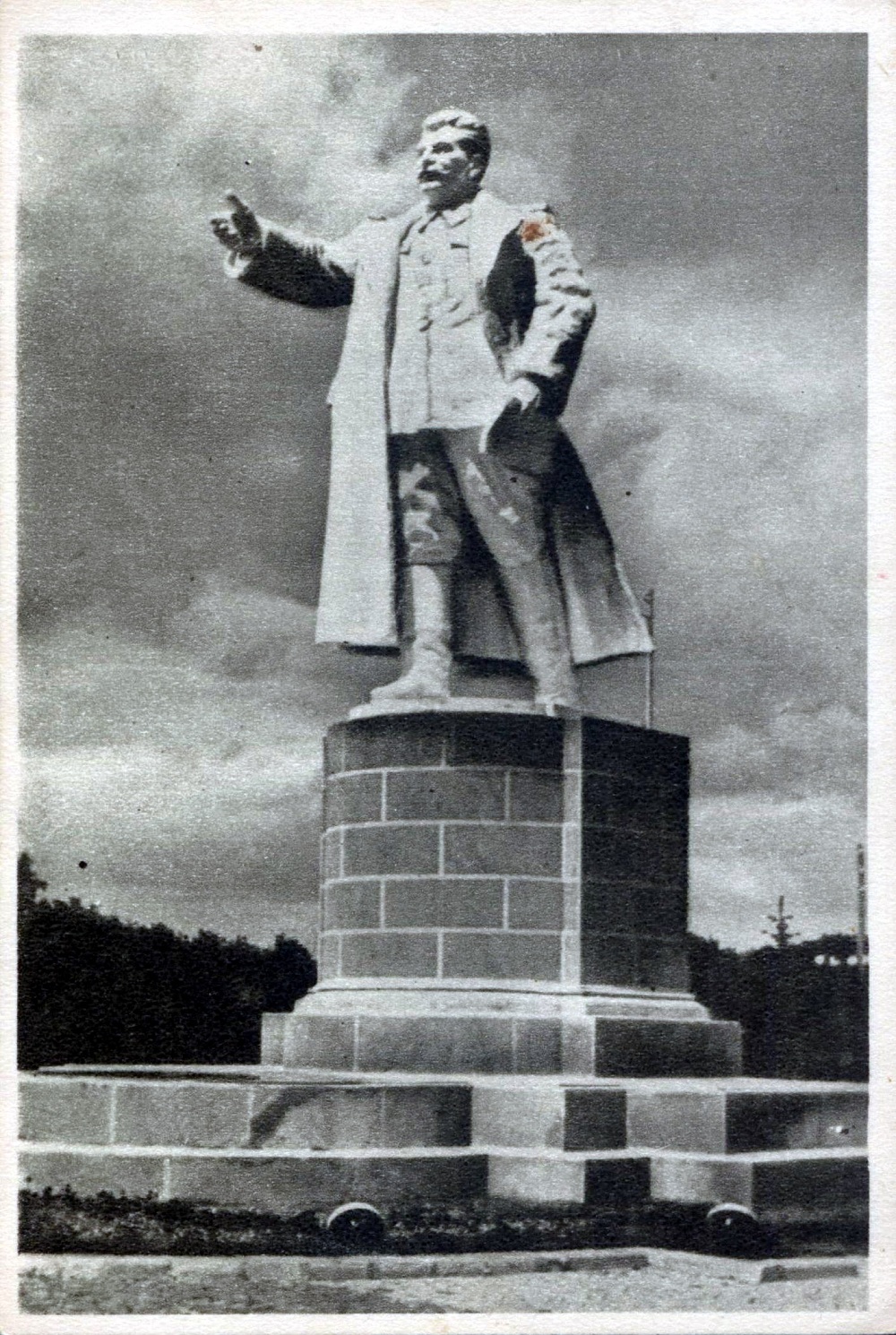

Broke and out of work, Demu responded to an open call for submissions to build a statue of Stalin. This statue would mark the entrance of I.V. Stalin Park, formerly Carol I and now Herâstrâu, in what is now Charles de Gaulle Square, at the time Stalin and formerly Hitler, Jianu and Aviatorilor Squares at one hard to recall time or another. [Note: this is the same Stalin that replaced, and was later replaced by, the Modura sculptural ensemble by Constantin Baraschi. See Part I.]

Demu was acutely aware of the risks involved. “…but how many problems would arise?…One who abandons, who pacts with the regime. Who immortalizes the executioner of millions of innocents?” He decided to enter the call in spite of his reservations. “I have to live, win my bread.”2 Miraculously, his named appeared as the last entry on the list of finalists, underneath names as prestigious as Boris Caragea, the sculptor of the notorious Lenin bronze [Note: See Part I] and a teacher of Demu’s, Ion Jalea, Milita Petrascu, and Constantin Baraschi, then considered a frontrunner for the prize.

Whether it was the formal value of his Stalin model, or simply the Russians’ view of him as a timid outsider more eager to please the regime than his esteemed colleagues, we’ll never know. But the commission was his. It took years, but the statue was completed and finally erected in its place in 1951.

Some say it was the slight hint of a smile that Demu cast on Stalin’s face. Some say it was the sculpture’s imposing size that so shocked and offended the liberal artistic community. Whatever the case, the bronze was ill received, especially by those artist colleagues Demu wished to please the most. He was demonized by those same peers almost immediately, some of them possessed by jealousy, some by a self-righteousness born, in Demu’s words, “of the ‘resistance’ of the corner café.”3 But their scorn was unquestionably endowed with the same depth of feeling resonating from Mukhina’s Worker, scorn that would follow Demu for the rest of his life and beyond.

In his memoir, La Sourire de Stalin, or “Stalin’s Smile,” published in France in 1977 and never again, Demu writes of being accosted by two men in front of his statue, around which he would walk late at night. The men beat him unconscious, and when he awoke, he found a letter in his pocket. Translated roughly from the French in which Demu wrote, “This is just the beginning. Next time we will hang you from the hand of the Stalin you made to smile…”4

Dumitru Demu, Statue of I.V. Stalin, 1951.

Dumitru Demu, Statue of I.V. Stalin, 1951.

Would the great Petrascu, if her model had been selected, have gone through with a monument to the man responsible for the death of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Romanians? Would Baraschi? Would he happily watch his Modura torn down to make way for an ode to Socialist imperialism? [Note: with Constantin, one would guess so.] It seems to a few of us now (fewer of us back then) that Demu’s restless exile was a sacrifice for those artists who also prospered under Bolshevism, many of whom composed the torch mob that eventually ran him out of town.

The Stalin bronze was torn down in 1962 during the era of de-Stalinization, and Romania’s general move away from the political leanings of the Motherland. [Note: the story is difficult to believe, but it is rumored that years later, when the great Ion Irimescu was asked by Ceausescu to sculpt a bronze of Sadoveanu, and the sculptor confessed he hadn’t the funds for the materials, Ceausescu offered him Demu’s smiling Stalin, which had been languishing in the basement of the House of the Republic, to melt down.]

In 1964, Dumitru Demu was forced by Romanian officials to relocate to his native Greece, which couldn’t have felt less like home to an Aromanian from Macedonia, and never to return to Romania. He decided instead to flee to Venezuela, where he had distant relatives and where, finally, he died of intestinal failure in 1997.

In 1970, I thought it important, if risky, to deliver an account of a man whose legacy is one long, burdensome walk through eternity. Our Wandering Jew, carrying on his back the projected shame of an entire artistic community, one that measured the degrees of its own complicity by his mark.

In 2017, the story seems as vital as ever.

[Author’s correction: In Part X of this series, the author wrote that the Vida’s Monument of Moisei was “composed of twelve carved oak columns arranged in a circle, each topped with a primitive mask speci c to the region.” The monument is actually comprised of ten primitive masks and two human faces.]

Dr. Igor Gyalakuthy is a professor emeritus at the Universitatea Nationala de Arte in Bucharest. In 1993, he received the national medal for achievement in the field of art history. He lives in Cluj-Napoca with his Lakeland terrier Bausa.

Notes

1 Dimitrios Demou, “Le Sourire de Staline” (Paris: Editions Universitaires, Paris, 1977).

2 ibid.

3 ibid.

4 ibid.