Two velvet club chairs nestle around a table and lamp. Books on shelves are punctuated by objects: an amp, a polaroid camera, etc. Set dressing includes botanical and entomological prints of moths or butterflies. Unremarkable enough not to draw attention to where they lean above the bookshelves, the prints make quiet reference to man’s taxonomic drive to arrange and classify. When Linnaeus named the order Lepidoptera, Samuel Johnson was making his Dictionary of the English Language and Diderot the Encyclopédie, a very different time for the book.

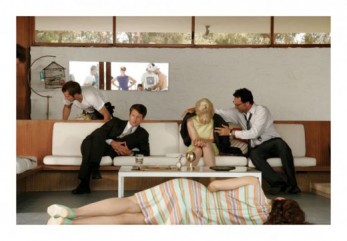

Sussman’s “Rape of the Sabine Women” is a break up of her 80-minute operatic film now projecting simultaneously in five acts at the Bass Museum. Her version of the tale transports Rome’s mythical history to an era loosely set in the 1960s with scenes that recall the neoclassical formula of Jacques-Louis David.

Alfred Hitchcock explains what a McGuffin is to Francois Truffaut with a story: It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men on a train. One man says “What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?”, and the other answers, “Oh, that’s a McGuffin.” The first one asks “What’s a McGuffin?” “Well,” the other man says, “It’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.” The first man says, “But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,” and the other one answers, “Well, then that’s no McGuffin!” You see, a McGuffin is nothing at all.

The Hamburger Bahnhof, a former railway station that now houses the Museum für Gegenwart, or Museum for the Present, is intimidatingly large. Seeing so few works of Kippenberger’s on its clinically austere walls is like viewing an eruption through a peephole, but the exhibition still manages to convey that he was a master of many styles—from abstraction to impressionism to realism—as much as a playful, sloppy interlocutor of conceptual games and unceasing appropriation. He was a man of highs and lows who dragged from the spectrum of his own experience.

The Lost Boys of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan are something of a misnomer. As the story goes, they were misplaced by their mothers and, having gone unclaimed for several days, were taken to Neverland. The Lost Boys barely had time to feel lost before being thrust into an environment that would inevitably shape their personal narratives. The sentiment is the same in Doğan Arslanoğlu’s and Johnny Laderer’s show at the David Castillo Gallery. Here, the story’s protagonists are not lost; instead, they are carving out a home, a narrative composed of intimate experience, nostalgia, the effect of place on a boy’s self-actualization.

Dark Nights of the Universe

Daniel Colucciello Barber, Alexander Galloway, Nicola Masciandaro, and Eugene Thacker

The occasion for this text was a four-night gathering in which each contributor gave a talk about hermeticism and Laruelle’s work. A version of each lecture is published here. But it is perhaps another, more tangential occasion that equally colors this work: that of the original text’s translation. “Du Noir Univers” was first translated for an exhibition catalogue for Hyun Soo Choi’s black paintings in 1991. So while the true concerns of “On the Black Universe: In the Human Foundations of Color” are ontological, it is perhaps forgivable to approach it aesthetically. The cover is printed black on black, and the text interspersed with stills from Aaron Metté’s 2012 video which shares the same title as Laruelle’s essay. It looks at home on Mayhem’s merch table.