Patricia Margarita Hernandez and Agustina Woodgate broadcasting in Berlin, Summer 2012. Photo courtesy of Patricia Margarita Hernandez.

The four artists discussed here who navigate within this port of call have unique approaches to addressing cultural logistics. This is visualized in several contexts including boating, illegal radio, the gray areas of global capitalism, and the relationship between fetish objects of vastly different cultures. The artist with the most direct approach to transportation is Justin H. Long. Having grown up in Miami, Long returned home after completing his MFA at CalArts. He inherited from his alma mater a strong tradition of mixing conceptualism with the rubble of pop culture. If he had grown up in LA, he would have made art about cars. But in Miami, it’s about boats. In a 2009 exhibition, Long presented the rivalry between the New York Yacht Club and San Diego Yacht Club, founded after the contentious 1983 and 1987 America’s Cup races, as a gang war for the bluebloods. In one painting, maritime flags on the knuckles of a fist decrypt to SDYC (San Diego Yacht Club). Through a periscope pointed at maritime culture, Long targets the bourgeois treacle once called seafaring. A recent piece, the “Ole 96er” (2009), is a cannon fashioned out of traditional boat making materials. Mounted on Long’s sailboat, this piece isn’t just theory, it was designed to shoot cans of beer at powerboats during the Columbus Day Regatta.

Justin H. Long, Detail of “The Ole 96er,” 2009. Cannon.Photo courtesy of the artist.

Another local artist invested in modes of transporting ideas and cultural goods is Patricia Margarita Hernandez. This summer in Berlin, she took a boat trip on her own of an invasive sort. Hernandez originally intended to pirate the radio waves with bootleg radio segments she had smuggled from Miami, but her scheme was thwarted when she discovered the owner of her scheduled location was allegedly linked to a family of litigious Gypsies. Circumventing this, she instead seized the opportunity to broadcast her segments online from a boat she commandeered with the help of Miami artist Agustina Woodgate.

Sea vessels were early platforms for unlicensed radio transmission—hence the cozy association with pirate mentality. Illegal transmission of air waves dates back to the dawn of radio. In a way, since it is unsanctioned and unregulated, it predates modern conceptions of radio. Even today, air space can be invaded from any undisclosed location with the proper equipment. South Florida especially has a unique brand fed by local D.J.’s to give voice to regional rap, hip hop, noise, Haitian music, and a collective microphone for eclectic discussion and commentary. This is coupled with the top 40 hits, often about Miami, that blare from passing cars. As a result, the blend of unofficial and official music creates a soundscape that is both central and liminal.

With the advent of online radio, pirating has become less about invading the airwaves and more about blasting past copyright and, in Hernandez’s case, international broadcasting restrictions for the sake of smuggling cultural gems and to provide a platform for the obscure. Some of the Miami-originated segments she brought to Berlin included songs by grunge rock musician Manny Mangos, a classical piano performance by Oscar Igñacio Bustillo (originally held in Hernandez’s studio as the fourth installment of her bedroom concert series), and artist Kevin Arrow’s mix of R&B intertwined with a Miami-based radio announcer Chico the Leo hosting his “I Love My Mama Check In” for his callers to give a shout out to their mothers and grandmothers. Among the numerous Berlin-based recordings she captured and will rebroadcast in Miami are a 24-hour theater performance by Ragnar Kjartansson and Davíð Þór Jónsson and a segment lead by Miami artist Magnus Sigurdarson. All Hernandez’s DJing was translated into Spanish as well.

Although Hernandez acted alone for the recent broadcasting operation, the event was an extension of the end, a well—established collective in Miami that switches their name to SPRING BREAK when the flood of tourists hit Miami Beach. Hernandez and her main collaborators Domingo Castillo and Kathryn Marks host screenings, exhibitions, lectures, site-specific projects, and workshops.

A project for her solo practice that also careened past any intellectual property lines was a public invitation to make “The Mix Tape You Never Made” (2012) by converting the technology of recordings on vinyl, CD, MP3 and audiocassette into one digital output. Among the eclectic variety of samples she sources are over 200 cassettes donated to her by the local library. A unique but unplanned synthesis occurs when music clips are interrupted by, say, Mandarin language lessons.

Both the aberrant nature of Hernandez’s D.J. catalog and Long’s excavation of subcultural tropes run through the varied practice of Nicolas Lobo. In January of this year, Lobo hosted a pop-up event in collaboration with the end at a multi-service store. These venues can be found in any city with an immigrant clientele looking for money transfers, phone card refills, bill payment options, and photography services alongside ethnically-specific souvenirs, jewelry, and, as often the case in southern Florida, ceramic pottery.

Nicolas Lobo, “Biscayne Wireless,” 2012. Lightjet print, 12 x 18”. Photo Courtesy of Nicolas Lobo.

All Lobo’s sculptures in this series can fit into a shipping tube, allowing him to set up his international version of a multi-service store anywhere in the world. Dubai is at the top of his list. Lobo’s investigation of these businesses started with a crash course in black market banking when living in San Francisco’s Mission District. “I used to get Western Union money transfers and they would give me cash that was stamped with the street gang logo…They were controlling the Western Union money because that was the flow of money going from the Mission back to Central America and they were taxing it somehow. So you would get your money and it would have Maras, the name of the gang, stamped on every bill.”

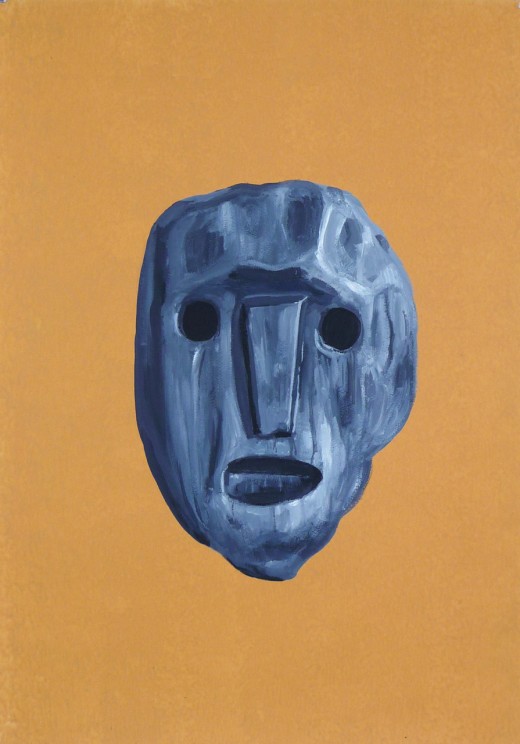

While Lobo has plans to disseminate his hybridizations globally, Bhakti Baxter investigates in the opposite direction, culling visual examples from international and ancient sources. One of his recent projects is a 100-part painting series of primitive figures on paper from cultures around the world. He explained how these objects inform us of their creators’ cosmological views, myths, interests in sex and food, and other universal needs. “Although they’re from extremely diverse and idiosyncratic cultures, when you see them together you start to see patterns,” said Baxter.

Bhakti Baxter, Work in Progress, 2012-. Tempera, acrylic, and gouache on paper.

Primitive art, in Baxter’s opinion, elicited one of the first acknowledgements by the western world of the existence of irrational and innate drives of the human spirit. He envies the belief systems that our early ancestors possessed and were so deft at articulating. “Their world view was never questioned. It was never like. ‘Oh, this is an interesting theory.’ It was like, no, the world is filled with spirits and we’re just one of them.” Replace spirits for radio waves or the digital transfer of funds, and you have a belief system that is not as primitive, nor foreign, as it first seems.

For these four artists, physical orientation regarding international borders also plays a role. Baxter starts with objects from distant origins and works inwards to the universal aspects of the human psyche. Long reconfigures a perpetuated narrative of local space. For Lobo and Hernandez, the goal is to transmit outwards and promote exchanges abroad. In a sense, one cargo container of the same information, but to different locations, produces unique outcomes. A new translation occurs.

As we cope with the effects of cultural globalization, it seems the message, as detailed in these four approaches, is to avoid homogeneity. And further, we must protect the viability of transmission structures by diversification. In today’s world, most of the communication that reaches us has filtered through the official channels of the state or the corporate structure (Twitter and Facebook, both lauded for their roles in recent uprisings, are both private companies). To circumvent these hegemonies, the artist often moves to quasilegal territory. We arrive at piracy.