"...generic and ubiquitous elements of urban life that reveal the composition of the contemporary city as a distributed network of patterned practices."

Moreno and his collaborator Ernesto Oroza pay close attention to Miami’s frayed urban fabrics and the spontaneous actions applied to mend them. They document them in the Tabloid, a series of newsprint publications produced in conjunction with installation projects. The latest issue is a study of “moiré houses”: homes used as part-time barbershops or bakeries, whose functional zoning flickers between residential and business, like the optically unstable overlaid grids of a moiré pattern. Other installments have examined the repetition of faux-stone ornament, Royal Palms in lobbies, sidewalk speaker systems—generic and ubiquitous elements of urban life that reveal the composition of the contemporary city as a distributed network of patterned practices. In Moreno and Oroza’s installation, the accumulation of found sculptures and the repeating designs of the newspapers covering the wall make this vividly palpable, while elevating the visibility of local practices scaled to human bodies over the busy geometries seen on Google Maps. “Whereas the global approaches of modern architecture relied on criteria extrapolated from an imaginary and ideal future, these new practices aim to start with an understanding of what exactly is needed and possible at a local level,” they wrote in “Learning from Little Haiti,” a 2009 essay for e-flux journal. “Teleology is replaced with radical pragmatics.”

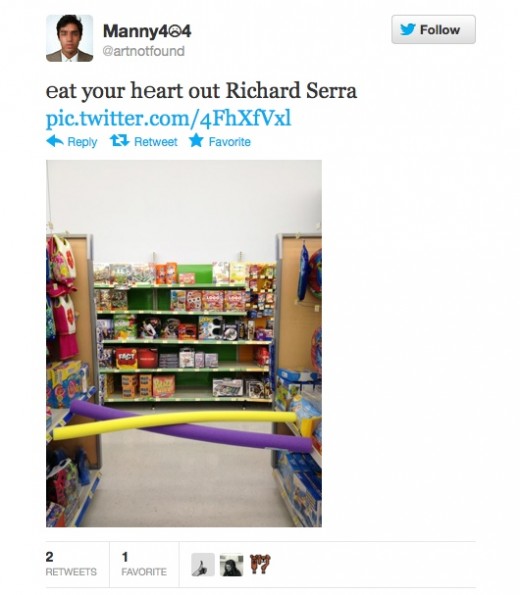

Twitter documentation of Art404’s WalmART project.

Art404, “5 Million 1 Terabyte,” 2010. 1 TB External Hard Drive, Illegally Downloaded Files.

Though they work in an environment of abundance, Art404 sometimes artificially create scarcity as a conceptual gesture. For their recent project “1 man 1 phone” (2012), Palou left his home on a Saturday morning with nothing but his phone and a charger, and became “homeless” for the weekend. He made a new Twitter account, @1man1phone, and used it to solicit strangers for food and shelter. His refrain: “I am Manny, a local homeless artist who could really use a meal. Could you help me out with some food?” As he tweeted this at other users in Miami, he walked around the city in search of available outlets so he could keep his phone charged. Sanabria was at the Conflux Festival, an annual weekend-long exhibition of performance and interventions in New York, running a projector with the Twitter window open and a map tracking Palou’s movements.

@1man1phone received some sympathetic replies. “thats pretty interesting. i hope you dont starve cuz unfortunatley society is in sympathical ruins!!!” wrote one. “i dnt think many homeless have phones,” said another. “you have pretty good grammer for a homeless guy” was another skeptical reply. Women who received his tweets said they’d be happy to help, but they worried he could be a predator. At least one user reported @1man1phone to Twitter and it was suspended just hours after it had been opened. Twitter’s Terms of Service lists violations that lead to suspension, but keeps it flexible: “What constitutes ‘spamming’ will evolve as we respond to new tricks and tactics by spammers.” Palou was perhaps guilty of sending “large numbers of duplicate @replies or mentions,” or maybe his tweets were identified as harassment. In a city where signs proclaim “No Panhandling Zone,” Palou experimented with begging on another system, and soon found new restrictions there. (His second account, @homelessmanny, managed to survive online until Sunday night when the project ended.) But offline he was inconspicuous. He still looked like a consumer. He could slip into the public bathroom at Staples where, to his delight, he found an electrical outlet and a shower, and satisfied the physical needs of his phone and himself.

In “1 man 1 phone,” Art404 acted out the alignment of urban space and information networks. I think of the work as a performative variation on Moreno and Oroza’s installations, where they visualize distributed and repeating connections by wallpapering their patterned tabloids around found sculptures. “The non-space of the ATM kiosk is no different from the collection of any-space-whatevers that constitute the cookie-cut corporate campuses of Omaha, Nebraska; Mumbai; and Santiago,” Moreno wrote in “Notes on the Inorganic,” published by e-flux this year. “[B]oth float freely, severed from their contexts, structured for particular ends.” Space becomes information. Consumers become information, too, as encounters between people and their urban environments are expected to be fast, transient, and gainful. Walmart wants its aisles to guide its guests through an easy shopping experience. Twitter generates individualized suggestions of users to follow, whose updates and links will be useful, at least as entertainment value. The problem of homelessness is not “nowhere to live” but “nowhere to go”: it begets lingering presence in the city’s channels of movement; it generates social and economic transactions that appeal to emotions less goal-oriented than desire. Spam clogs the Twitter feed, distracting users from their information consumption, vaguely threatening them with viral infections. The identification of homelessness and spam in “1man1phone” paths evoked the slightness between expectations of the navigation of internet space and movement in the city, and how one man with one phone builds connections amid the online and offline fields of the any-space-whatevers. Taken together, the work of Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza on one hand and Art404 on the other construct a panorama of the systems that govern everyday life and the people who negotiate and respond to them, across a broad spectrum of images and voices.