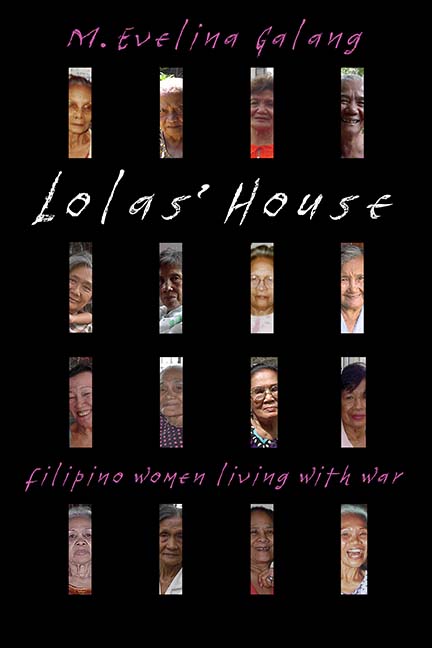

The Lolas Speak and Testify: Lolas’ House by M. Evelina Galang

Christine Hyung-Oak Lee

In M. Evelina Galang’s Lolas’ House, sixteen Filipino comfort women recount their experiences of kidnapping, torture, and sexual slavery during World War II by the Imperial Japanese Army. These are a handful of many testimonies history has yet to record with any depth, and which the Japanese government has repeatedly denied. Lolas’ House changes the landscape by documenting first-person accounts by Filipina comfort women in hopes that these stories never die. On both the part of the lolas and Galang, this book is the accumulation of a life’s work.

One by one, the lolas—or grannies in Tagalog—sit down with Galang, whose Fulbright grant facilitates her journey to the Phillippines and research. Over the course of the next decade Galang transcribes the lolas’ words and writes Lolas’ House. It is harrowing work.

The narrative is written in present tense, broken up by the interjections of the narrator, summoning the reader back. Galang, too, is protecting herself from the horrors of the testimonies, aware of the writer Iris Chang, who suffered from depression and succumbed to suicide while researching the Bataan Death March. Galang writes: “I know what it means to be born an American of immigrant parents, and to return to that homeland to hear the stories of wartime rape and torture on your elders, to feel the drive to right that wrong. To make a promise to see that justice done in the face of the impossible. Even if your only weapons are words, are testimonies, are stories.”

Galang dances, literally dances, around the main narrative of testimony. She dances with her dalagas and with the lolas, and tells us so. Despite their pain, there is still joy in the lolas’ world. And in providing relief for themselves, they provide relief to the reader so that we can push on through their testimonies. So that we right the wrong. So we see justice done.

Someone once told me that details in a story are an indicator of veracity. And these testimonies, especially those of atrocities committed upon loved ones, are told in great detail.

“They had no mercy, Evelina,” says Urduja Francisco Samonte, as she describes how babies were sliced out of pregnant women. “Then they take that baby and they toss him high to the sky and make a game of skewering newborn infants on the tips of their swords.”

Lola Atanacia Cortez and Lola Philomena also witnessed torture right before being raped: fingernails pulled out from fingers, and fathers skinned alive before them.

In contrast, the lolas seem to go numb in the telling of their own stories, dissociating from the scene; there is an absence of self, the negative space, which frames the trauma they survive. “They used me,” and “they raped us.” Viola Lanzarote tells Galang. “They did like that to me. You know—day and night—they did like that to me.”

Urduja Francisco Samonte’s heartbreaking description struck me in particular: “I could feel my skin slipping out of me, I could feel my body gliding out of hands and sliding into the sweaty uniform of another.” Her body becomes the soldier’s body. Her body is taken.

The lolas’ narratives aren’t presented in any identifiable order; not chronologically or by date of capture. And yet they accumulate in horrifying intensity, an essential structure choice by Galang. I found myself choosing to read Lolas’ House in the light of day, instead of my usual bedtime, because it was giving me nightmares. The terror, trauma, and despair of the comfort women are palpable. It makes you want to put the book down. It makes you want to clap your hands over your ears. But the narrator stops the reader from doing so in order to bear witness. This is necessary terror, artfully presented.

Lolas’ House is the first collection of direct personal testimonies from Filipina survivors to join the canon of comfort woman literature, which includes novels by Nora Okja Keller and Chang-rae Lee, as well as Maria Rose Henson’s autobiography, and the scholarly work of C. Sarah Soh. Now, with Galang’s important contribution, the lolas’ voices are on record.

The lolas are now dying in their old age, but with Lolas’ House, Galang ensures their stories stay alive by recording them in history. Midway through the book, Galang states, “The lolas were true to their stories. Mostly because the curse is that they cannot forget.”

Christine Hyung-Oak Lee is the author of the memoir Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember and a forthcoming novel The Golem of Seoul, both by Ecco. She can be found as @xtinehlee on twitter.