The Dakota Access Pipeline

Kai Bosworth

A horseback rider crosses the Oceti Sakowin Camp at sunset. August 27. Photo by Annabelle Marcovici

A horseback rider crosses the Oceti Sakowin Camp at sunset. August 27. Photo by Annabelle Marcovici

Decolonization at its core seems to have a self-evident definition: the process of ending colonialism. But the definition immediately belies its simplicity: what, exactly, are the political, legal, and psychological parameters of colonialism? What happens if most of the members of a particular place do not accept that they are the perpetrators of colonialism? What strategies are necessary for initiating a broader decolonial process? These are exceptionally difficult questions to tackle, and provide part of the reason why activists and theorists alike have begun to vigorously return to critical decolonial thought, especially over the last ten years. While the American left largely (if only occasionally) supports ending American imperial efforts abroad, rarely do we reflect on the equally explicit conditions of settler colonialism perpetuated within.

Smoke rises from a campfire at the Camp of the Sacred Stone. July 17. Photo by Annabelle Marcovici

It is shocking how infrequently non-Native peoples or “settlers”—including those of us on “The Left”—consider that we inhabit dispossessed land. If this fact is recognized, oftentimes it is seen as a crime committed sometime in the past, in a now-irreversible moment of conflict in the Wild West that closed a sad chapter in American history. In fact, many aren’t even aware that Native Nations still persist

to this day. This willful ignorance structures our political formations in sometimes unexpected ways. Consider, as Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang do, the political language of Occupy Wall Street. The move to reclaim public or economic space for a multicultural—if disenfranchised—99%, Tuck and Yang argue, is a re-enactment of the settlement of this continent. The language of occupation would perhaps be less appropriate than one of deoccupation. Yet many of us also use the language of decolonization in these spaces, as if we could “decolonize the university,” “decolonize our diet,” or “decolonize the city.” Although each of these is not only possible but desirable, when coated with the veneer of liberal social justice and redistribution of wealth, a significant portion of the material redistribution of land and authority necessary for decolonization is lost. Decolonization becomes a stand-in concept for feel-good localism. The word turns into a comfortable metaphor for “something that feels radical.” Tuck and Yang write of what it would take to resaturate decolonization with its material possibilities:

For social justice movements, like Occupy, to truly aspire to decolonization nonmetaphorically, they would impoverish, not enrich, the 99%+ settler population of United States. Decolonization eliminates settler property rights and settler sovereignty. It requires the abolition of land as property and upholds the sovereignty of Native land and people.

Here, decolonization requires not simply a multicultural life of appreciation of Native culture, but a material secession of land and political power to indigenous peoples along with the abolition of the territorial borders of the United States. A seemingly impossible demand—yet should not all demands aspire toward the impossible? Years ago, stopping the Keystone XL pipeline seemed impossible, as did stopping DAPL just months ago.

Although often implicit, central to any decolonial project is a critique of capitalism. At least three major reasons for retaining anti-capitalism in decolonial movements can be singled out: first, capitalism is responsible for the initial moments of European colonization. This included not only the violent seizure, sale, and settlement of North and South America from hundreds of Native Nations, but also the inability to see the land as even being used by these inhabitants. John Locke famously argued that the supposed inefficient use of land by the “needy and wretched inhabitants” of North America justified its appropriation to laboring settlers. Second, capitalism has a constant need for the raw materials to fuel labor and leisure. Throughout history, black, brown, and indigenous bodies and lands have been targeted for their cheap status and easy disposability. This is as much the case with DAPL today as it was with uranium mining 40 years ago, hydropower 60 years ago, or gold 130 years ago. Importantly, dispossession is also a global project—it is no surprise that the mining industries in the US and Canada have been and continue to be closely tied to those in the settler colonies of South Africa and Australia. Finally, essential to original and ongoing dispossession is the conversion of land—through labor—into private property, measured only by a supposedly secular value structure of exchange. The maintenance of landed private property in the US, including nationalized property like the American parks system, is demonstrative. There is no place in capitalism for protecting the sacred, for only value is sacred under capitalism.

By contrast, the liberal response to the blockade, to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, and to indigenous peoples more broadly has lamented legal and procedural injustices and sought to ameliorate them through compromise. Liberalism, broadly construed, might be taken as a commitment to self-determination of all peoples ensconced in civil or political rights that uphold the economic system outlined above. If only the tribal government had been properly consulted about the pipeline as part of the environmental review process, the logic goes, their sacred sites and the borders of their reservation could have been avoided and no environmental justice concerns would have been raised. In a standard Lockean fashion, Native Nations are understood as defending land that is rightfully theirs, in the same way that private property owners should be able to defend land that is rightfully ours. The injustice of the pipeline for liberals is primarily that its oil is likely headed for export—as if proper national use of oil could be justified. Somewhat shockingly, many holding this position assume that there could be some institutional solution for handling the individual grievances of Native Nations, as if colonialism and capitalism could each be legislated away, bit by bit, until we arrive at justice.

Glen Coulthard calls these stances liberal strategies of recognition that attempt to diffuse the power of anti-colonial struggle without challenging the basic hierarchies of liberal democracy. Recognition is understood by the process whereby the state no longer pretends Native Nations do not exist, but instead appeals to them to become part of its overarching political status quo. Recognition can work in several ways—for example, there are 535 federally recognized Native Nations in the United States who are afforded some manner of legal protection. This explicitly excludes hundreds of other tribes, who for arbitrary reasons continue to be denied political status by the federal government. Political recognition can lead to recognition of privative tribal cultural rights to perform religious practices or prevent their ancestors and artifacts from being desecrated or displayed in museums (to the extent that these rights exist, many might be shocked to learn that they have for only twenty to forty years). The federal government retains the power to recognize its citizens and to grant them exclusive rights not available to non-citizens or criminals. Remember: in its foundation, American democracy was largely exclusive to white men who owned property. These practices skirt decolonization for a path toward accommodation and assimilation. The strategy enshrines the federal government’s position that Native peoples are domestic dependent racial or ethnic groups that compose part of the multicultural tapestry of America, rather than political nations in their own right. The retention of this power of recognition by the state allows the status quo of dispossession of Native Nations to continue unabated while appearing as a properly political arbiter.

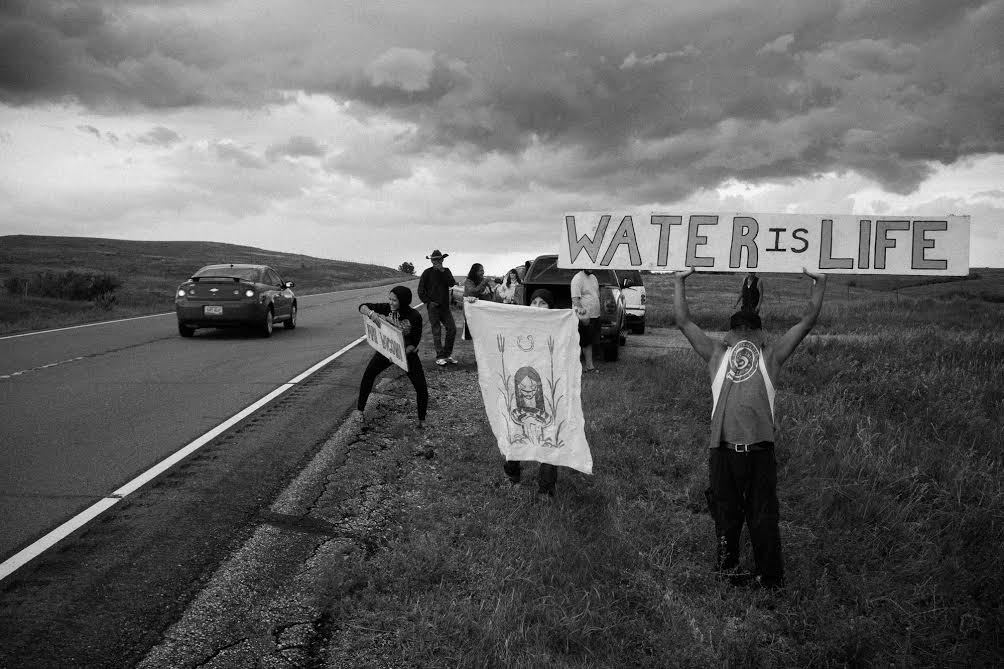

Sacred Stone campers hold signs, including one reading “water is life,” along highway 1806 in Cannon Ball. July 26. Photo by Annabelle Marcovici

What is dispossessed from Native Nations is not the holding of a piece of property, or an understanding of one’s life and livelihood as a piece of property. Dispossession is, in fact, quite the opposite: a seizure of Native lives, land, water, and livelihoods by way of private property and the inequalities in value and non-value that it bequeaths on space. Dispossession is: the poisoning of land or water upstream from places of settlement; the forceful destruction of language and culture by boarding schools; police and military violence; sexual violence pointedly wrought on Native women; enforcement of Eurocentric understandings of race, gender, sex, sexuality, or nationhood; and more. As if all of this weren’t enough, the combinatory planetary politics of climate change and fossil fuel extraction, transportation, and combustion themselves promise a new era of dispossession of indigenous peoples the planet over. Each of these strategies deprives Native Nations of the material relations that are required to fully and collectively maintain themselves. It is a testament to the ingenuity and tenacity of Native Nations that history is littered with successful acts of resistance, small and large, to these attempts at dispossession—from the environmental justice organizing of Women of All Red Nations (W.A.R.N.) and the American Indian Movement (A.I.M.) in the 1970s to Idle No More and the movement to change sports mascots to countless numbers of elders passing down knowledge, skills, and language to their youth.

How might seemingly innocent strategies of recognition conceal these deplorable acts of dispossession? State recognition works only as long as the baseline parameters of the colonial situation can escape unscathed from the encounter—that is, federal governance over territory and maintenance of the legal edifice that supports private property through force. State recognition is privative—it recognizes aspects of Native Nations as long as they properly fit into the parameters of the State’s categories of culture, religion, territory, governance, or nationhood. In the process, it plays the differences among Native Nations against each other, as it likewise does against and among all those “recognized” in some ways as people of color, immigrants, workers, women, and queer and gender-variant people.

A man from Standing Rock holds his daughter as they watch 4th of July fireworks in the Native American town of Little Eagle, South Dakota. July 04. Photo by Annabelle Marcovici

This use of privative recognition has a global history and present; indeed, Coulthard draws heavily on the work of Martiniquais philosopher, psychoanalyst, and revolutionary Frantz Fanon. Writing in the 1950s and 60s, Fanon was a key strategist of decolonial movements in North Africa, and of a theory of decolonization more broadly. Fanon was an advocate of the seizure of the State institutions by way of violent political struggle. From the vantage point of a settler colonial situation, however, aspects of the earlier understanding of decolonization might seem somewhat outdated. For the African nationalist movements, decolonization seemed to have a set of rather clear outcomes: the overthrow of legal, administrative, and military rule by European powers and the instantiation of self-determination. Yet Fanon’s travels are not so simple. He also recognized that colonized peoples were in a bind, for many were colonized as much psychologically as subjects as they were politically. They had come to desire recognition, which promised freedom, equality, and material wealth. Consequently, material struggle for control of land and political institutions was as much a struggle over the ability to constitute one’s collective mind and political situation in a new manner. It is through that material struggle—through the reappropriation or expropriation of land—that that psychological activity could begin to take place.

All of this has utmost importance when one places decolonization as the only proper response to disastrous climate change and the beginning of the Anthropocene, signaling both the symptom of dispossession and its exacerbation. In Louisiana, at the same time as the blockade in North Dakota, the Isle de Jean Charles (IdJC) Band of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw were already being resettled as flooding due to climate change will subsume their land on the coast of Louisiana. The oil industry has exacerbated the coastal situation by dredging canals for pipelines that destroyed freshwater wetlands along the coast, increasing the possibilities of coastal and inland flooding. Despite 500 years of colonialism, the water protectors on the frontlines in North Dakota oppose the pipeline not simply for themselves and their children, but for everyone downstream and all those affected by climate change.

Academics like myself arrive too late to the event taking place, and often fall prey to parasitism on the frontline struggles. Instead, it is our responsibility to combat wherever possible the appropriation of these frontlines to the liberal politics of recognition and—more than ever now—to a populist climate politics that subsumes decolonization as merely one environmentalist strategy that fits alongside green capitalism, localism, and multiculturalism. Coulthard argues in an interview published in Jacobin (January 2015):

My one concern and my one insistence is that [pipelinestruggles] not be framed as simply an environmental issue but one of decolonization and framed through the lens of indigenous sovereignty. It’s too easy for environmentalists to play their ally card in a very instrumental way. A decolonial frame of analysis is needed, where you demonstrate how central indigenous peoples’ struggles are to blocking these types of reckless development projects and also the alternative cultural bases that can emerge in their wake.

Not just on the high plains, but for all of us in North America, decolonization is imperative. Decolonization demands that we let go of much to which we are attached: our cherished histories, our land, our authority, and much of our wealth. It is not mere recognition of the centrality or importance of that struggle or movement over there, but an abolition of the political and economic relations that uphold settler sovereignty and white supremacy worldwide. Kai Bosworth is a PhD candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of Michigan.

Kai Bosworth is a PhD candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of Michigan.