Toward South Florida Aesthetics: An Oral History of GUCCIVUITTON

Jarrett Earnest

Serge Toussaint painting a mural at GUCCIVUITTON in Miami's Little Haiti neighborhood.

JARRETT EARNEST (RAIL): How did you start GUCCIVUITTON?

LORIEL BELTRAN: I guess we were frustrated with what Wynwood had turned into.

ARAMIS GUITERREZ: We started talking about putting our money where our mouth is and opening a gallery together. One of our major concerns is that Miami is a large importer of culture. We wanted to work against that, to create a space for what is already here. We started looking for venues and decided on a building in Little Haiti—I’ve had my studio upstairs for about five years and Loriel lives around the corner. We know this area. It is a good mix of everything. Because it is on a border, different classes and different cultures come together here. We’re at the end of Little Haiti, which has a large Haitian-American community and borders the diverse middle class neighborhood of El Portal.

RAIL: So Aramis, how long have you been in Miami?

GUTIERREZ: I’ve been here about nine years. I moved here from New Jersey and before that I lived in New York. My initial experience was different from Loriel’s. When I arrived here I thought it was fantastic. I was really fed up with New York and the Northeast, and everything in Miami seemed so accessible and everyone seemed friendly. Over the years my perception of this place has been readjusted by the reality of the lame things I’ve seen happening here. My involvement with this gallery initially came a little bit out of spite, like to say “This is how it’s done, this is how easy it is. Stop messing around with the formula.” I wanted to do something very simple and show some very worthy art that was all around us.

RAIL: How did you invent the name?

GUTIERREZ: We were brainstorming and I said “GUCCIVUITTON” as a joke. To my horror Loriel and Domingo looked at each other like an eureka moment had just occurred. We were trying to find something that fit the area so we started thinking about the refugee culture of Little Haiti. A lot of the stores here cater toward refugee culture and its needs: calling cards, fake brands to send home, things to make your look like you are doing well even though often when you get to a new country you’re really struggling. So we started thinking about knock-off luxury brands.

BELTRAN: That is one part of the “aspirational” aspect of Miami. I think the other part deals with the aspects of gentrification. Wynwood had just happened, officially. The Design District had just announced it would become another mall for the super rich. So I think a lot of art spaces were being displaced by super-luxury. GUCCIVUITTON as a name was about art that is super-luxury. It is a little political in a sense because its being aware of the process of gentrification: we are moving to a new area, which can potentially happen again whether we like it or not. We came here because we wanted a place to see shows without seeing a hundred bad murals on your way into a gallery. A more neutral space, a more real place, because Wynwood just feels so fake, it’s just cheesy.

***

Art404, MAYBE LEGAL APPAREL, [Pepsi vs Coke, A Flock of Airlines, Maybe Legal HD (purple one with audi rings), All Burger Everything, All Metal Everything, All Cute Everything (murakami/hello/ kitty), All Intro Everything], 2013. Custom printed t-shirts, chrome hangers, chrome spiral display stand, Dimensions Variable.

IRL (In Real Life)

APRIL 20 – MAY 25, 2013

GUTIERREZ: About the time that Chavez died we all got fucked up and were celebrating. We had just about finished renovating the gallery space and realized we needed to have a strong first show. Loriel said, “Lets do an ART404 show.”

BELTRAN: ART404 are two Venezuelans who grew up in Miami and Broward. Three years ago one of them got into Cooper Union. They had been collaborating and liked what they were doing so the other one said, “Fuck it, if you’re moving to New York I’m coming too.” They are super young post-internet kids. Everything they do is super-smart; dealing with hacking and pirated material. They did this piece where they put five million dollars worth of pirated data on a terabyte hard drive. So they claimed the drive to be worth five million dollars, but they were selling it as a sculpture for $2,000, thus were playing with market value. From there they did a piece with someone from the hacker group Anonymous. Anonymous hacked their page and sent them an email saying, “Hey, I hacked your page because I thought it was funny you are called 404, but I like what you are doing.” So 404 proposed to collaborate with them, sending them a list of the top art websites in the world and asked them to take them down for a couple minutes, and send screenshots. So they got a screenshots from Gagosian, David Zwirner, etc. with a 404-Error notice to document the performance.

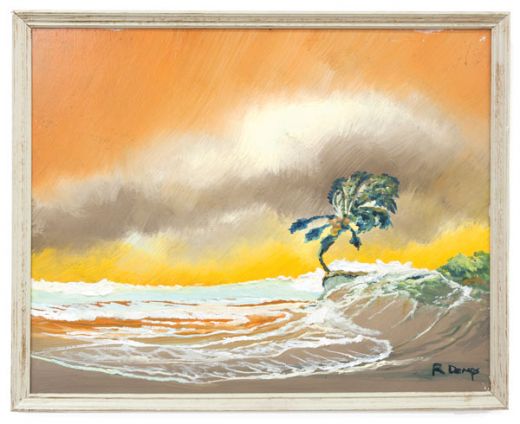

Rodney Demp, Seascape, Date Unknown. Oil on Upson Board, 23” x 191⁄2”.

JUNE 22 – JULY 27, 2013

GUTIERREZ: I have a friend named Scott Armetta who makes these beautiful little haunted Florida landscapes. A lot of my friends elsewhere had tried to show him but it never materialized. I wanted to think of a way to contextualize his work in a contemporary setting. We decided to do a group show with other people in South Florida who continue this practice of going out and painting en plein air. We started doing research and discovered the Highwaymen, a group of 50 to 60 African-American artists who made these painting in production lines to make a living. These paintings were initially tourist curios you took away from your vacation in Florida. But then some of the artists began to develop their own unique language and had a flair for the subtle nuances of painting. They established a language for the type of landscape painting made in South Florida to this day. We found a bed and breakfast in Mount Dora that had a lot of these paintings that we borrowed for the exhibition. This show helped bring in a whole different group of art connoisseurs —the ones who feel uninvited to the contemporary-art game.

BELTRAN: We chose contemporary artists who aren’t Sunday painters; they are people who are very aware of contemporary art but opt to make landscape paintings instead.

GUTIERREZ: It was a really sweet show, somehow it avoided being pretentious.

RAIL: This is the kind of thing that could be treated very ironically, or jokey, because some of these paintings are on that edge.

BELTRAN: The presentation was key. We installed it so beautifully, seriously, in a way you expect to see contemporary art.

Hugo Montoya, Stolen Boulder, 2013. Found boulder, enamel paint, steel rod, Dimensions variable.

Cause Living Just isn’t Enough

SEPTEMBER 13 – OCTOBER 12, 2013

GUTIERREZ: When we first decided to do the space we wanted to do a show with Hugo because we felt he was an underappreciated artist and that he really knows how to push people’s buttons in a good way. We let him move into the space for two months and he started making these horrible sculptures that had nothing to do with the ideas he originally talked about. We decided to just see where this is going for a while before we intervened and eventually we had to say, “We like your initial ideas and you need to have the confidence to go with them.” He felt they were so simple that they were stupid and wouldn’t work—as if just being himself wasn’t enough. For instance he initially started with this boulder idea. He presented the idea of building a giant gallery-filling boulder, then it became more pragmatic, shrinking to a real boulder.

BELTRAN: He then out and stole this boulder from The Machine Gun Experience, a machine gun shooting range in Wynwood. It was half-painted orange.

GUTIERREZ: At first he was going to put it on a pedestal but it was like 500 pounds. It was going to crush the pedestal he made, so he put a steel rod in the center to hold it up. It was so dangerous when we set the rock on the rod moved around on its own for 20 minutes until it settled. Once it was installed it was such a magical thing without the pedestal. It was just so “Hugo.” It was beautiful, really dumb, and it could kill you.

BELTRAN: People thought it was papier-mâché. It was at eye level so it was almost like you could hug it. It had a nice presence, like a figure. They would touch it and it would move and they would realize. “Oh shit! It’s a real rock.”

GUTIERREZ: There were other pieces like these pedestals that came down from the ceiling. On one of the pedestals you have a photograph of a white family and the other a tormented chimp—It really did activate the space beneath and between them because you had to squeeze between the pedestals to look at either but you couldn’t look at both photos at the same time.

BELTRAN: The white family and the chimp forced you to make these relationships like “Why am I thinking this?” Some people got offended too.

GUTIERREZ: The next piece was one that Hugo talked and talked about making, so much that we insisted he make it. This piece was a wall made out of clay from Biscayne Bay that came from a historic blacks-only beach.

BELTRAN: He’s kind of like a grown-up kid. He’s playful, and a lot of artwork grows out of that persona. Like the chimp-white family pedestal piece, the wall had some racial buttons that he was pushing. Race for him is an obsession.

GUTIERREZ: It had never occurred to us before but these racially charged pieces began to make sense. Hugo is not only brown but he’s a huge, stalky guy. His physicality magically offends a lot of people who don’t know him. I’ve been around on a few occasions where for no reason old white ladies were particularly uncomfortable in his presence. This and the way he maintains that persona really played into the show. So to do this black-beach piece he started this three-week task of going out with my cooler and digging up clay from the beach and taking the public bus back. One night we locked him in to make the piece by himself. The result was just striking. It started off very dark, moist, and had this earthy smell and then over the weeks it became stark white and cracked, and continued cracking—it never fell apart. It became more interesting as a piece about a historical black beach as its appearance transformed.

The last piece in the show was a large wall vinyl of a painting his friend’s mom had made. One that he grew up with. It is the only painting she ever made—a naked woman riding a centaur, taken from the cover of a video game magazine.

BELTRAN: It’s called “Oscar’s Mom.”

GUTIERREZ: It’s perfect as the first and last painting you ever make.

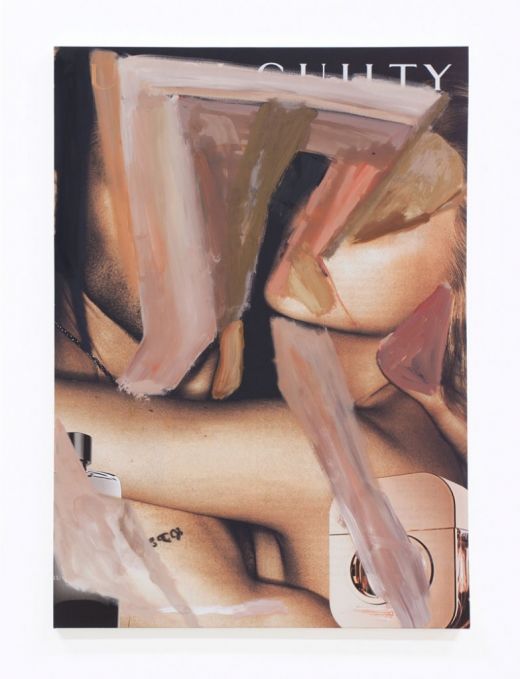

Loriel Beltran, Primitive Couple #2, 2013. Oil on Glicee, 30” x 40.”

Rococo Chanel

OCTOBER 19 – NOVEMBER 23, 2013

BELTRAN: I did a proposal for Bal Harbour for a public work for the city. So I started looking at “high-end” aesthetics—I wanted to abstract them, to break down the structures and materials. A lot of it was skin-tones, copper colors, gold, precious materials, marble. I started abstracting high-end ads to get at the structure of visual pleasure through form and consumption and how it is exploited and utilized in branding. I didn’t get the commission but that became the work in my show, paintings, and sculptures.

RAIL: How did your own work evolve as it related to being in Miami, or of “local” or “colloquial” aesthetics?

BELTRAN: I’ve been in Miami for 14 years. The first ten I completely rejected it—like “I want to get out of here,” but I never left. I always avoided anything “Miami.” Then after a decade you start feeling connected to a place and start knowing it better, and I began incorporating more elements of Miami in my work. To me it seemed normal that if we were going to open a gallery it would have to relate to this because everyone is trying to figure out what Miami is. It’s a relatively new place where everything changes so quickly.

RAIL: The works of yours I’ve seen have to do with re-purposed construction materials, pre-cut marble counter-tops, and things like that. They have a lot to do with surface and have a very glamorous materiality even though they are deconstructed—everything about that feels like Miami to me.

BELTRAN: I was always interested in systems of production. The marble came from the homes being foreclosed during the recession. I knew so many people who were going into houses and ripping out the pipes, appliances, marble countertops—so I like that these semi-precious items are then circulating back into a black market. It was the idea of the stone’s reality contrasted with the fakeness of the housing market. Everything was on credit and not really there. They also have the idea of “façade,” architectural elements that are stuck on—when people want to appear as more—those are aspirational elements.

Cristine Brache, About, 2013. Dye Sublimation Print on Chiffon, 55″ x 27″.

I Know the Master Wasted Object

NOVEMBER 30, 2013 – JANUARY 11, 2014

GUTIERREZ: Christine Brache is a Miami native who moved to Beijing. She was pursuing this narrative that explored sexual tourism within China as a Caucasian woman looking at Caucasian men and their questionable interactions as outsiders in this culture. She made a video piece that was like R. Kelly’s “Trapped in the Closet” but instead it was a drama that unfolded as an online chat between a male protagonist and women that work in brothels. It was a weird show for us because it entered a political space that maybe we didn’t initially fully understand. But then we started to think about Miami’s culture and how it is made to be consumed by tourists. Her work had a nice echoing effect with what goes on here during Art Basel. During these fairs nobody comes to South Florida to indulge in our culture. They come to consume their own culture in South Florida. So we ran it during the fair to emphasize this very empty one-sided relationship.

BELTRAN: It was a tricky show. Some people thought she was touching on something that wasn’t really personal to her. She also became the tourist in that work because she had no real context within that, at least none that was being communicated within the work.

Joseriberto Perez, green when wet (left) little pink shores i know not (right), 2014. Oil on Canvas 9 x 12”

A Durable Scale of Values

FEBRUARY 8 – APRIL 5, 2014

GUTIERREZ: Joseriberto was an artist we met very early in our programming phase. We walked into his studio and automatically knew we were giving this guy a show. His work was colorful, super South Florida, and he was just trying a lot of different aesthetic solutions. He had previously shown in the wrong venues and was frustrated; if you’re a punk band you won’t find acceptance on POWER 96. We decided to give him a year to prepare and he showed up with a hundred paintings that really ran all over the place. It was the hardest to curate because he had enough work to do a couple shows of different kinds of paintings. We thought about doing something like that but it didn’t really speak to his practice, which is dynamic and non-linear. Then we started coupling works together that had a similar thought process or theme and decided to do a show of paired paintings, even though they were all individual works. Some of the paintings I found the most striking were very light in color and had these hair-thin black bands around their perimeter which tightens the space and sucks it together. Instead of morphing out onto the wall and getting lost it becomes an object with an imperceptible frame holding everything together.

RAIL: When you say these abstract paintings are very “South Florida” what does that mean to you?

GUTIERREZ: I feel like he pulls form the flora and fauna and architectural trends of South Florida. He is open about his interest in recycling our history and feeding it to us in a contemporary way.

BELTRAN: One way to describe it is to say he is a reflexive painter. He is drawing from the language that is around him and he is in Miami—they look “from here” without being cliché.

Guyodo, Untitled Idols, 2012-2014. Installation view. Mixed Media on Wood.

APRIL 18 – MAY 31, 2014

GUTIERREZ: Because of the neighborhood we were in, we knew we wanted to do something with Haitian artists, but finding them was challenging at first. It was kind of a pipe dream until a friend of ours, Tomm El-Saieh, mentioned one day that his family owns the largest collection of Haitian art in Port-au-Prince. He was familiar with all the artists so he could provide access to their work. Things came together quickly and in surprising ways. Another friend of ours, Diego Singh, mentioned one day that there was a movie called “Heading South” (2005) with Charlotte Rampling about sexual tourism in Haiti. The thing about “Heading South” is instead of Caucasian men going down to Haiti for prostitution, it was middle-aged women coming down to party with these young islanders. The movie is framed around a politically unstable time in Haiti toward the end of the Duvalier years. These women are aware that their lovers’ lives are consumed by the political turmoil but are powerless to do more than provide them with pleasantries. Charlotte Rampling is often referred to as “the look” and is cast for her severe expression. This is where the name came from. People look at Haitian art with certain expectations; they expect it to be “voodoo” and “primitive” and “islander.” The artists are well aware that outsiders want this from them and they in turn make art to meet this demand. Some of the original Haitian Masters were approached by Caucasians and told “hey this fence ornament you made is really great, you should make it as a sculpture.” In this instance, the eye of tourist and the local aesthetics of the artisans came together to create new opportunities for art. I think ultimately this was a positive thing as it created a new type of aesthetics and enabled further generations of artists. We wanted to do a show that explored this.

We also relied a lot on Adler Guerrier, who helped us find some contemporary Haitian American artists, living in Miami. That expanded the perspective, and was an interesting facet of this situation.

BELTRAN: Haitian art usually gets displayed as artifact, and we wanted to treat it just like contemporary art—presented in the way that we understand. Most people came in and said, “its great that you are involving the Haitian community,” but I felt like it was the other way around. It’s not about us teaching the Haitian community about contemporary art, its about the Miami art community learning what is already here.

The AmerTec building, designed by Chayo Frank. Hialeah, USA.

CHAYO FRANK

Sculptures, 1969 – 2012

JUNE 28 – AUGUST 09, 2014

GUTIERREZ: Chayo is an artist who comes from an architectural background. He studied under Bruce Goff and pursued organic architecture. According to Chayo, Goff described his work as the next step in the evolution of organic architecture in that his designs were almost purely an aesthetic experience. When he graduated, his father offered to let him design the offices for their warehouse in Hialeah. Today this is known as the AmerTec building in Hialeah and is a standalone marvel of local organic architecture. After that I don’t think he got many offers to make more buildings because people just thought they were nuts, so he went into the family business and stopped making work. In the early 2000s he began again to pursue his artistic endeavors. While he was building the AmerTec building he had been making sculptures that he perhaps had intended as models for future buildings and he started making them again. He made a few of them every year in his house on this carpeted pedestal. I think by the time we were introduced to his work, it was a show that we didn’t have to make a choice. He is so South Florida, he’s one of us if you like it or not. It had to be done.

***

GUTIERREZ: Florida has always been a transient pioneer state. Because of that, people come here for the opportunity to do whatever it is they want to do. Miami may attract more hedonists, and central Florida might be home to more do-it-yourself types, but Agustina is totally right. I know I’m here because it allows me to do things that I want to do and wouldn’t have the opportunity to do elsewhere. You can even be someone like Chayo Frank here! No one here is looking over your shoulder. People come here thinking “when I get to Florida what I say goes.” It’s the perfect place to explore your own bad taste. That is what goes on here, it can seem obnoxious to outsiders, but it also occasionally allows interesting things to happen.

BELTRAN: It’s very informal too. That’s the culture of the place. It’s casual and fun, although sometimes the party atmosphere is distracting. Like when you have something like Wynwood it turns into a party place. The heat is also a factor. Right now it’s hot and I want to have a cooler full of beers. This informs how we interact with each other.